The Heian Period (平安時代) began when Emperor Kanmu (桓武天皇) moved the capital to Heian-Kyo (平安京) in 794, which is now known as Kyoto (京都).

The circle indicates the time we discuss in this section.

During the Heian period, emperors ruled Japan. However, early in this era, the Fujiwara family, a wealthy aristocratic family, held actual political power. The Fujiwara family managed to marry their daughters to emperors, thereby gaining power through these marriages. The family was called “Sekkan-ke” (摂関家), meaning the guardian’s family or the emperor’s representative.

In those days, aristocrats led an elegant, refined lifestyle while cultivating a graceful culture. Many essays and novels were written by female authors during that period. The most famous one is “Tales of Genji (源氏物語)” written by Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部). The Imperial Court often held ceremonies followed by elaborate, lavish banquets. This imperial social life played an important role in advancing aristocrats’ political careers. Women also actively participated in these ceremonies. Many high-ranking officials owned several large estates. Sometimes, their daughters inherited these properties and lived there.

Courtship methods were quite different back then. To start a romantic relationship, a man would write a poem called “waka” for the lady he was interested in and have his servant deliver it to her, hoping she would write him back with a similar poem. Once she accepted him, he was allowed to visit her for short periods from a distance. As their relationship grew deeper, he would visit her more frequently and stay longer. After they married, and if she was his first legal wife, she would live with him in his house. If she were not his first legal wife, she would remain in her own home, and he would visit her for a few days or longer. The wife’s family raised their children. In those days, and until the next Kamakura period, a woman’s lineage was considered important. By the middle of the Heian period, emperors regained political power because their mothers were not from the Fujiwara family.

Scenes from the “Tales of Genji”. Bought in Kyoto.

Scenes from the “Tales of Genji”. Bought in Kyoto.

Origin of Samurai

Although the Heian Imperial court and aristocrats lived with grace and elegance, they lacked the political power to govern the country. There were numerous thieves, frequent fires, and constant fights everywhere. Consequently, the Imperial court, aristocrats, and temples began hiring armed guards or security forces to protect themselves and maintain public order. These hired guards were the origins of bushi (武士) or samurai (侍). Samurai extended their influence and gained more power by forming groups and suppressing uprisings. Eventually, two powerful samurai clans emerged: one was the Heishi (平氏), often called the Heike (平家), and the other was the Genji (源氏). Gradually, they gained power in the Imperial court. After many power struggles among them, the Heishi started to control the Imperial court by marrying their daughters to the emperors. In the later Heian period, political power shifted to the Heishi. They became tyrannical and arrogant. This behavior created many enemies. The Genji clan and the Fujiwara family started a war against the Heishi. The Genji pushed the Heishi to the final battlefield known as Dan-no-ura (壇ノ浦) in 1185 and defeated them. This battle was the famous Genpei-Gassen (源平合戦). The fall of the Heishi marked the end of the Heian period.

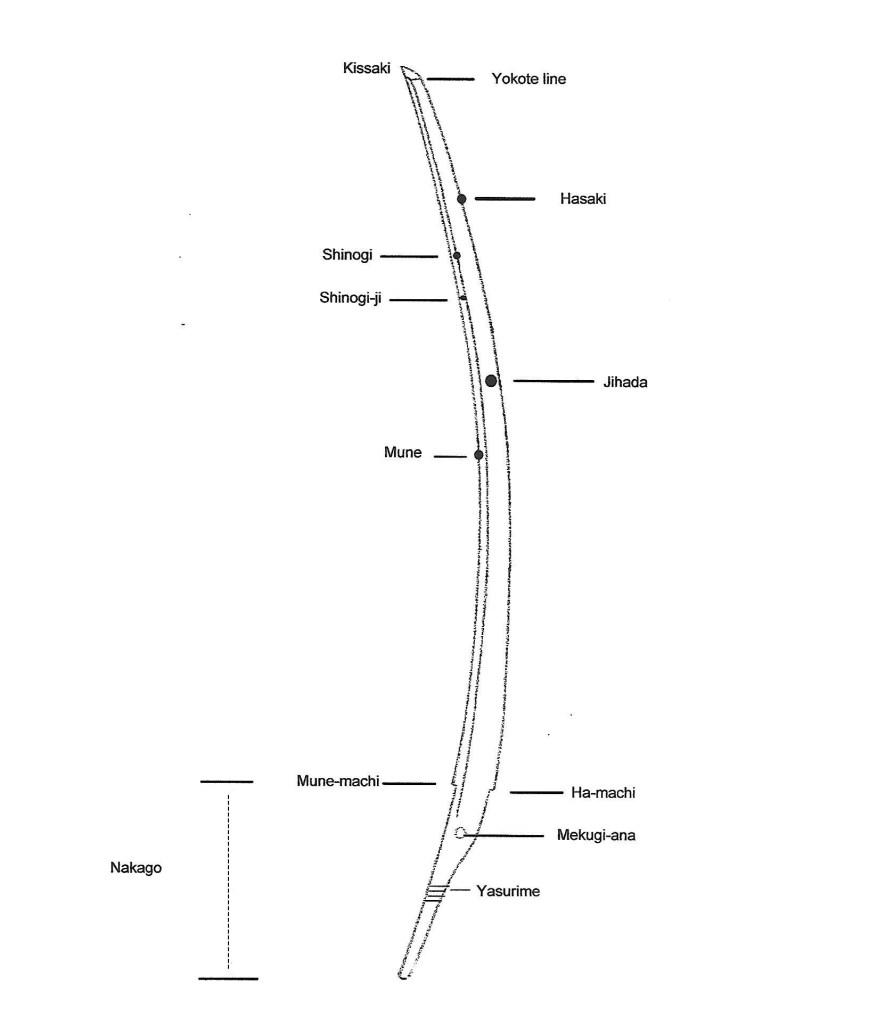

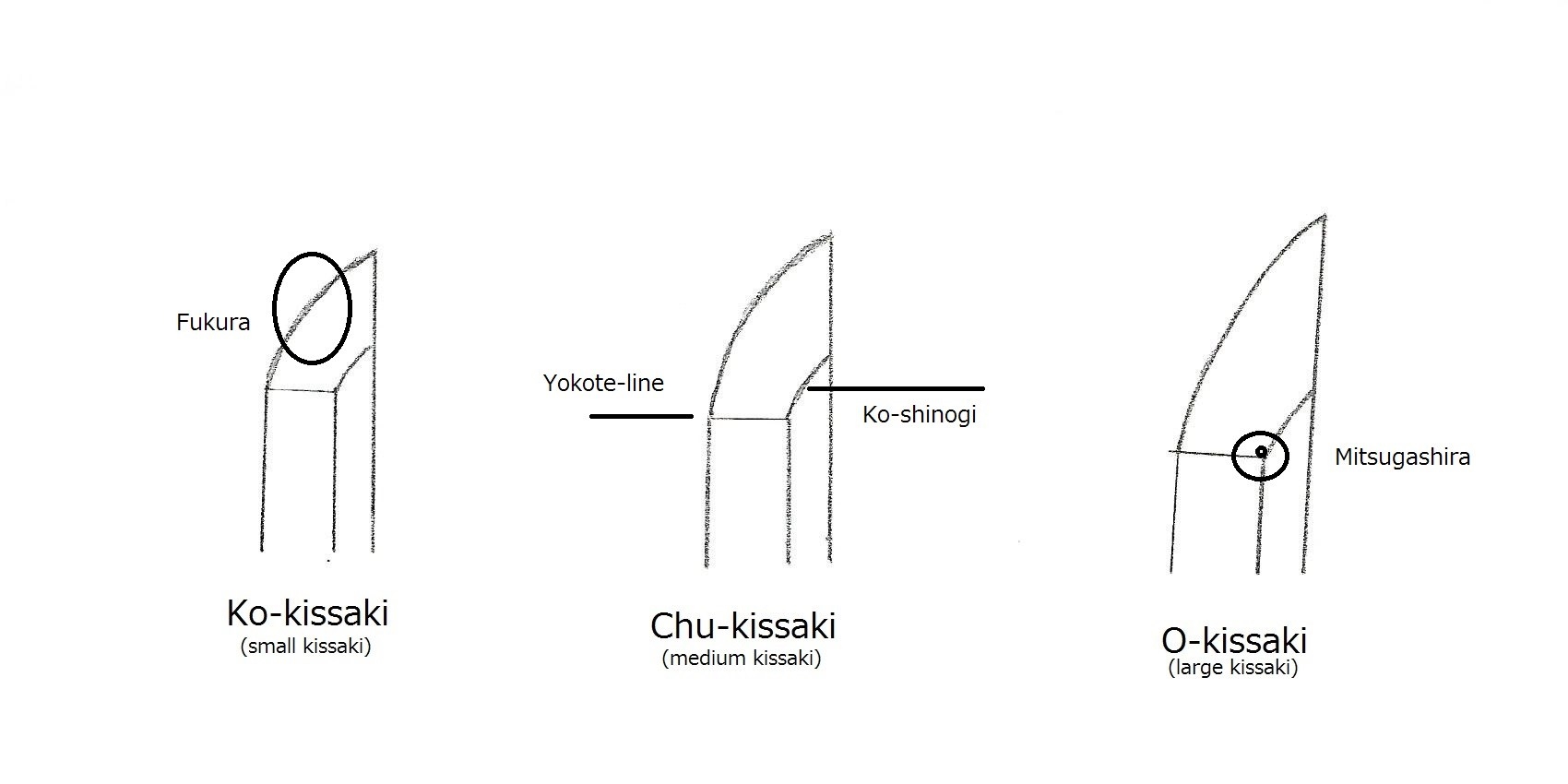

During the Heian period, curved swords appeared for the first time. Before that, swords had straight blades. Historical studies of Japanese swords start from this point. The elegant, refined lifestyle and culture created by the influential Fujiwara family were reflected in the swords’ style. A group of swordsmiths in the Kyoto area created a distinctive sword style known as Yamashiro-den (den = school). The shape of their blades exhibits a graceful line. The most famous sword in the Yamashiro-den is the Mikazuki Munechika, by Sanjo Munechika (三条宗近) below, which is a national treasure today. The Yamashiro-den style represents the swords of the Heian period.

Sanjo Munechika (三条宗近) from Showa Dai Mei-to Zufu (昭和大名刀図譜) by NBTHK Owned by the Tokyo National Museum.