The circle represents the time we discuss in this section

GENKO 元寇 (1274 and 1281)

Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, attempted to invade Japan twice, in 1274 and 1281. Both times, a powerful typhoon struck Japan. The Mongols sent a large number of soldiers, along with all kinds of supplies, on numerous ships to Japan. These ships had to stay very close to each other, side by side, front and back, within the limited offshore area of Kyushu. When the strong winds arrived, the ships swayed, collided, and capsized. Many people fell into the ocean, drowned, and lost supplies in the water.

Although Mongol soldiers landed and fought against the Japanese army, they had little choice but to retreat from Japan due to a typhoon and shipwrecks. As a result of this strong wind, Japan was saved, and it seemed like Japan had won. This was when the famous Japanese word “kamikaze” (divine wind) was created.

The Mongols had far superior weapons compared to the Japanese. They had guns, which the Japanese did not. Their team fighting tactics were far more effective than the Japanese’s one-on-one combat style.

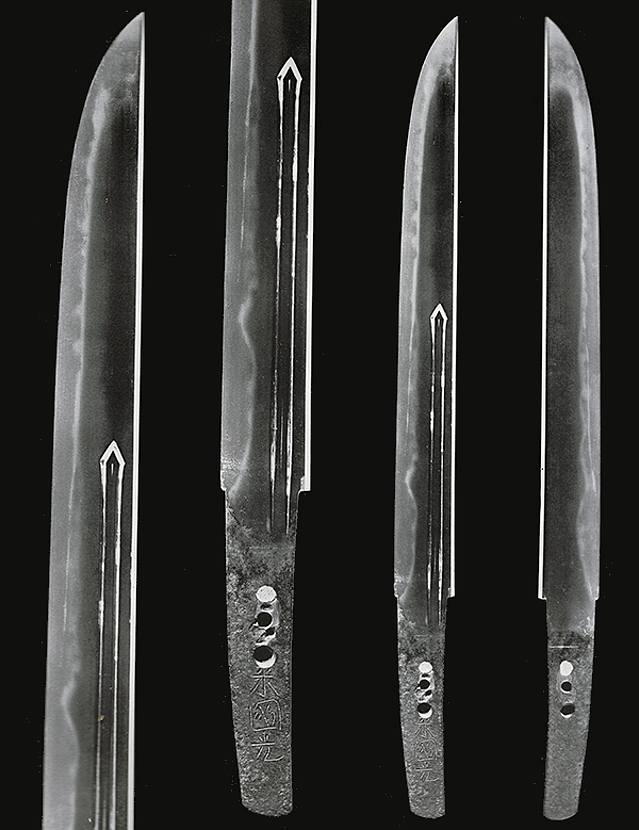

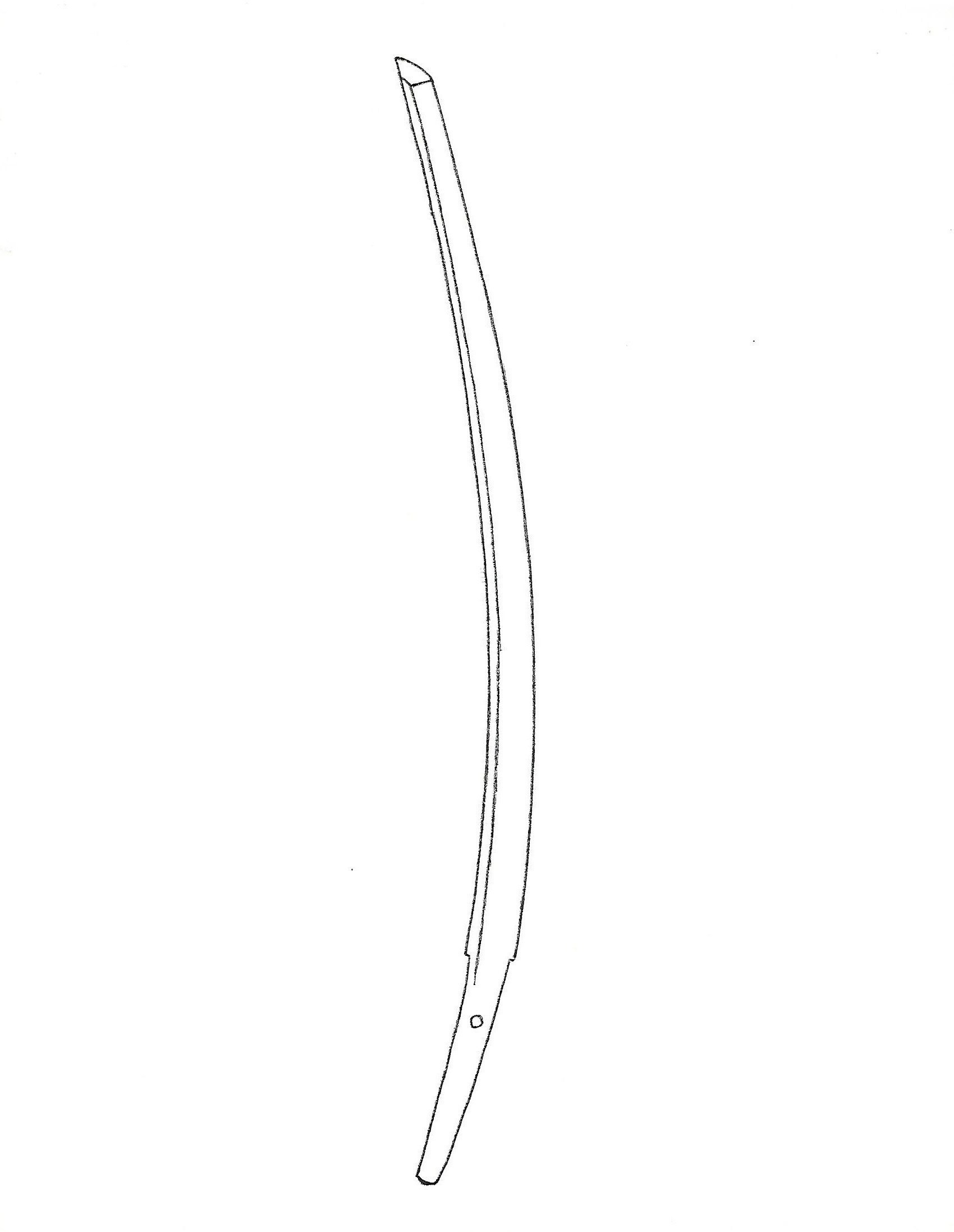

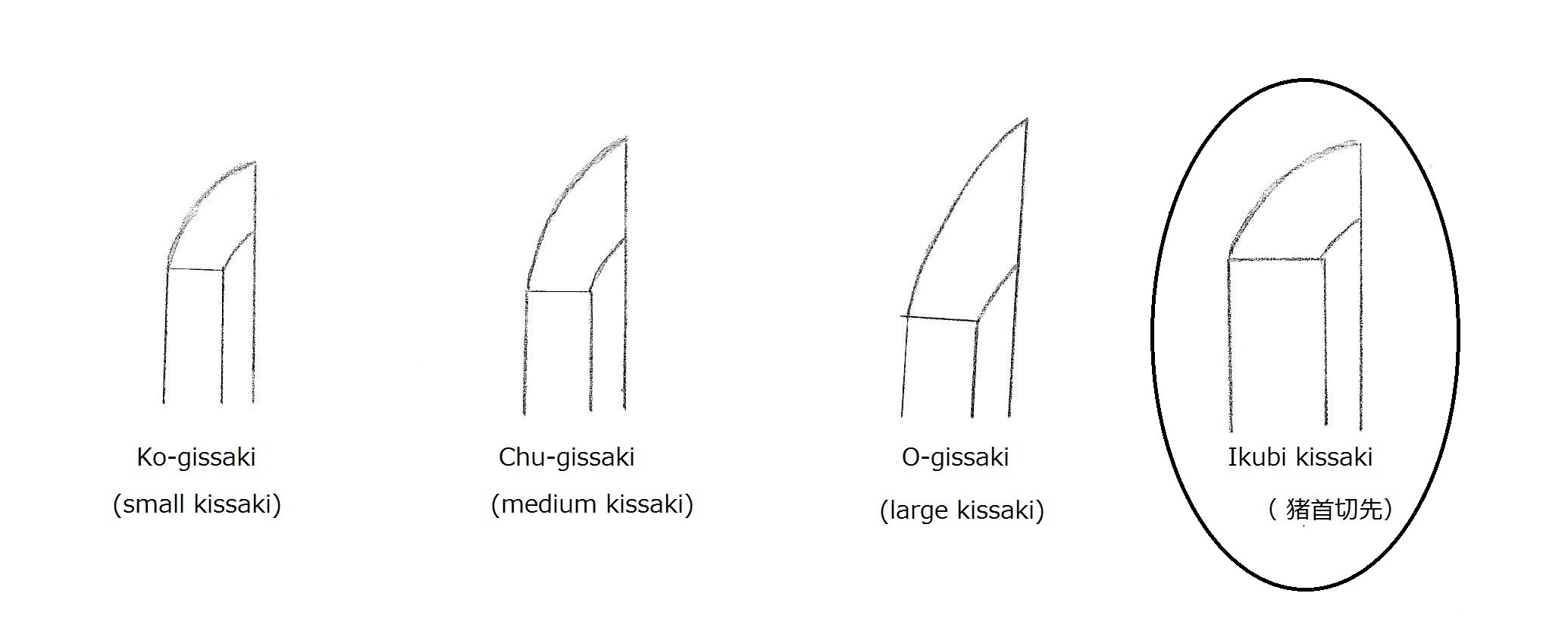

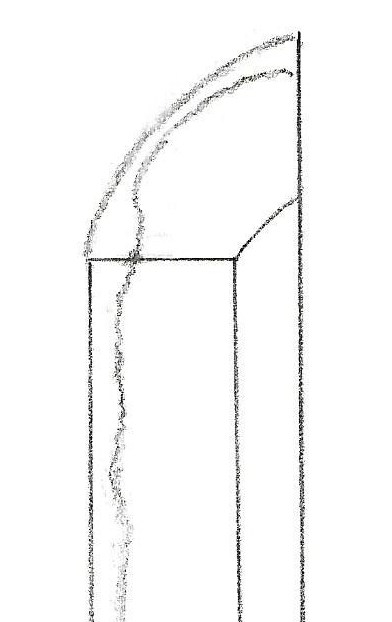

After the Mongolian invasion, it became clear that the Ikubi-kissaki style sword needed to change. When swords were used in battle, the most frequently damaged part was the kissaki. Japanese soldiers primarily used ikubi-kissaki swords in this war. An ikubi-kissaki tachi has a short kissaki. When the damaged part of the kissaki is whetted out, the top part of the yakiba (tempered area) disappears, and the hi (a groove) rises too high into the boshi area (the top, triangle-like section). The short ikubi-kissaki becomes even shorter, and the hi rises too high into the boshi area. Aesthetically, this appears unattractive. Functionally, it does not work well. To fix this flaw, a new style started to emerge toward the end of the Kamakura period.

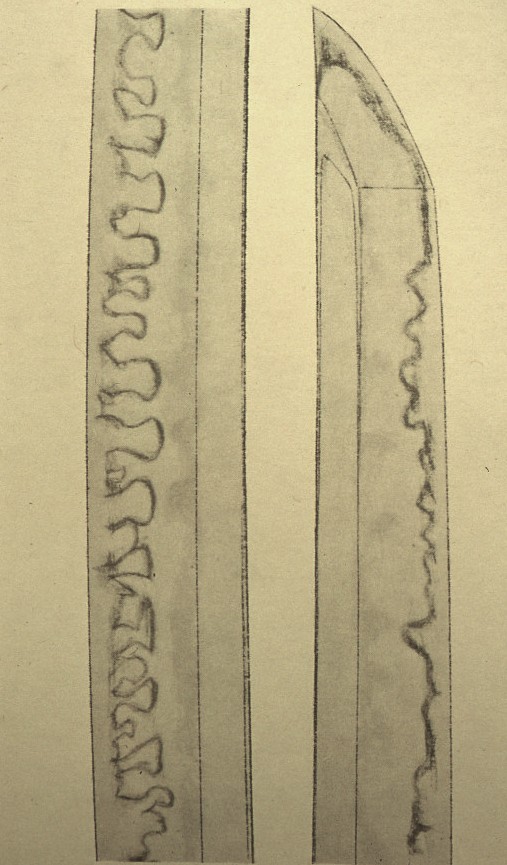

During the latter part of the Kamakura period, swordsmiths began creating a new style to address this flaw. Additionally, pride and confidence grew among people after driving the Mongols away, which was reflected in the appearance of swords. Generally, the hamon and the sword’s shape became stronger, more pronounced, and showier.

The Kamakura area prospered under the Hojo family’s rule. Many swordsmiths moved to Kamakura from Bizen, Kyoto, and other regions during this time and created a new style. This marks the beginning of the Soshu–den (Soshu is the Kanagawa area today). Many renowned swordsmiths appeared during this period.

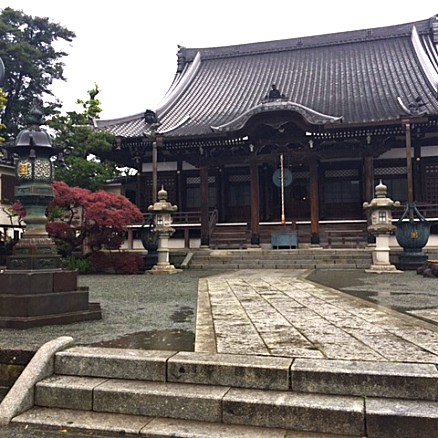

One of the famous swordsmiths is Goro-nyudo Masamune (五郎入道正宗). You can easily visit Masamune’s tomb in Kamakura. It is located at Honkaku-Ji Temple, about a 5 to 6-minute walk from Kamakura train station.

While I was attending Mori Sensei’s (teacher) sword study group, I studied with a student who is a twenty-fourth-generation descendant of Masamune. Although he does not carry the Masamune name, he has been making excellent swords in Kamakura. He also makes high-quality kitchen knives. His shop is called “Masamune Kogei (正宗工芸).” It is a short walk from Kamakura Station. To find his shop, ask at the information center at the train station.

来国光(Rai Kunimitsu)

来国光(Rai Kunimitsu)

Kawazuko-choji O-choji Ko-choji Suguha-choji (tadpole head) (large clove) (small clove) (straight and clove)

Kawazuko-choji O-choji Ko-choji Suguha-choji (tadpole head) (large clove) (small clove) (straight and clove)

Sansaku-boshi

Sansaku-boshi

Osafune Nagamitsu(長船長光) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Osafune Nagamitsu(長船長光) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

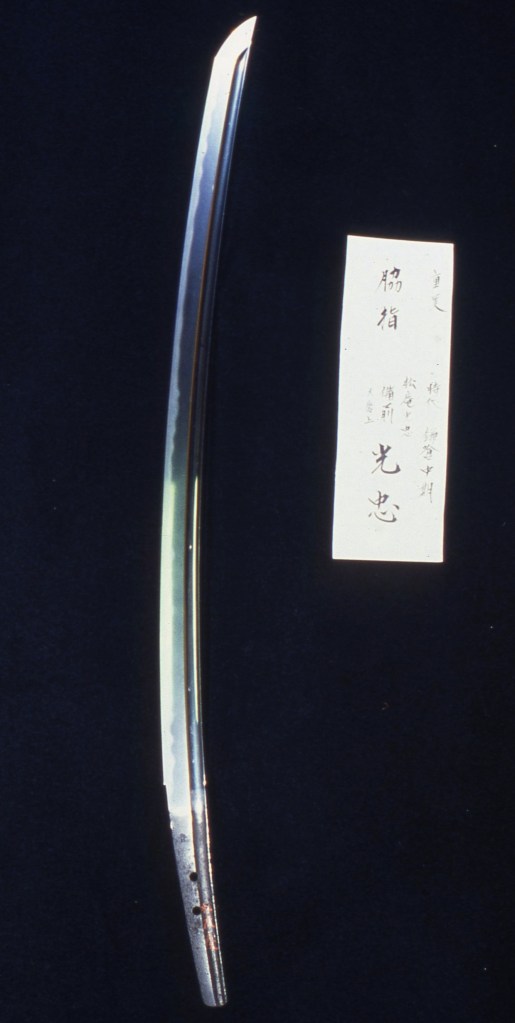

Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠) Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠)

Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠) Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠)