This is a detailed section of Chapter 13, Late Kamakura Period, Genko(鎌倉末元寇). Please read Chapter 13 before reading this section.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section.

Genko (元寇): Mongolian Invasion

Chapter 13 briefly describes the Mongolian invasion. Here is a more detailed description. The Mongol Empire was a vast empire that stretched from present-day Mongolia to Eastern Europe during the 13th and 14th centuries. The grandson of Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, sent several official letters to Japan demanding that it become a dependent state of the Mongol Empire (元: Yuan) and ordering Japan to send tribute. They threatened Japan, warning that they would invade if Japan did not meet their demands. Hojo Tokimune (北条時宗), who was in power at the Kamakura bakufu (government) at the time, refused and ignored the letters multiple times. This led to two invasions by the Mongol Empire. It is often said that a powerful typhoon hit Japan on each occasion, and these two powerful typhoons drove the Mongols away. This is correct, but the whole story was much more than this.

Bun’ei-no-eki (文永の役) 1274

The first Mongolian invasion was called Bun’ei-no-eki. In early October 1274, Mongol troops (Mongols, Han Chinese, and Koreans) totaling around 40,000 men* set out from the Korean Peninsula on about 900* large and small ships and headed toward Japan. After arriving on Tsushima Island (対馬), Mongol soldiers burned villages and killed many residents, including local villagers. Villagers were captured and sent to the top Mongol officials as slaves. It was a heartbreaking scene.

The Mongols moved to Iki Island (壱岐の島), Hizen Shore (肥前), Hirado Island (平戸)、Taka Island (鷹島), and Hakata Bay (博多). In each location, the disastrous and sorrowful scenes were the same as everywhere. On every battlefield, Japanese soldiers and villagers were killed in large numbers. The Kamakura bakufu sent a large number of samurai troops into battle. The Japanese forces sometimes won and pushed the Mongols back, but they mostly lost. Many Japanese wives and children near the battlefields were captured.

Eventually, no soldiers dared to fight the Mongols. The Mongols’ arrows were short and not very powerful, but they coated the tips with poison and shot them all at once like rain. Also, this was the first time the Japanese faced firearms. The loud sound of explosions frightened horses and samurai. Japanese troops had to retreat, and the situation was grim for them. But one morning, there was a big surprise! All the ships had vanished from the shore. They were all gone on the morning of October 21 (today’s date, November 19). All the Mongols had disappeared from the coast of Hakata.

What happened was that the Mongols decided to end the fight and head back home. The reason was that, although they were winning, they had also lost many soldiers and one of their key leaders in the army. The Mongols realized that no matter how many victories they achieved, the Japanese kept coming more and more from everywhere. Also, the Mongols realized they could not expect reinforcements from their homeland across the ocean. Their supplies of weapons were running low. The Mongols decided to go back. However, there was a twist. Around the end of October (November by today’s calendar), the sea between Hakata (where the Mongols were stationed) and Korea was very dangerous because of bad weather—only clear days with south winds allowed sailing across the sea. The sea they had to cross is called Genkai Nada (玄界灘), known for its rough waters. For some reason, the Mongols decided to go back during the night. That was a mistake. They might have caught a brief moment of the south wind, but it did not last long. Consequently, they encountered a usual severe rainstorm. Many ships collided with each other, crashed into cliffs, capsized, and people fell into the ocean. Several wrecked vessels were found on the shores of Japan.

The Mongol invasion ended here. This war is called Bun’ei-no-eki (文永の役). The Mongols lost many people, ships, soldiers, food, and weapons. In fact, Korea suffered greatly. They were forced to supply the Mongols with people, food, weapons, and more. After the war, in Korea, only older men and children were left to work on farms. Additionally, they faced both drought and prolonged rainfall.

Ko’an-no-eki (弘安の役) 1281

The second Mongolian invasion, known as Ko’an-no-eki, occurred in 1281. After the first attempt to invade Japan, Kublai Khan kept sending messengers to Japan, demanding that Japan become a Mongol dependency. The Kamakura bakufu ignored and executed these messengers. Kublai Khan decided to attack Japan again in 1281. His top advisers tried to persuade him not to go through with it because the ocean was too dangerous, the country was too small, the distance was too far, and there was nothing to gain even if they succeeded. Despite these, Kublai Khan insisted on the attack.

This time, they arrived in two groups. One was the east-route troops with 40,000* soldiers on 900 ships, and the other was the south-route troops with 100,000* soldiers on 3,500 ships. This was one of the largest forces in history. They planned to depart from their designated port and meet on Iki Island (壱岐の島) by June 15 to fight together. The east-route troops arrived there before the south-route troops. Instead of waiting for the south-route forces to arrive, the east-route troops started attacking Hakata Bay (博多) on their own. However, since the previous invasion of the Bun’ei-no-eki, Japan had prepared for battle by building a 20-kilometer-long stone wall. This stone wall was 3 meters high and 2 meters thick. The troops had to give up landing at Hakata and moved to Shiga-no-Shima Island (志賀島). There, the fight between the Mongols and Japanese was evenly matched, but ultimately, the east-route troops lost and retreated to Iki Island, where they decided to wait for the south-route forces to arrive.

The south-route troops never arrived. They had changed their plans. On top of that, while waiting for the south-route forces to come, they lost over 3,000 men to an epidemic. Some suggested returning home because of the difficulties, but they chose to wait for the south-route troops as long as their supplies lasted.

Meanwhile, the south-route troops decided to head to Hirado Island (平戸島), which was closer to Dazaifu (太宰府). Dazaifu was the final and most important place they wanted to attack. Later, the east-route troops found that the south-route troops had gone to Hirado Island. Finally, the two forces joined on Hirado Island, with each group stationed on a nearby island called Takashima Island (鷹島). The problem was that the ships were not easily maneuverable because this island had very high tides and low tides.

Meanwhile, 60,000 Japanese men headed toward the area where the Mongols were stationed. Before the Japanese soldiers arrived to fight the Mongols, a massive typhoon struck on July 30, and the Mongols were caught in a huge storm. Their ships collided, and many sank. People fell overboard and drowned.

By this time, it had been about three months since the east-route troops left Mongolia in early May. That means they had been at sea for roughly three months. In northern Kyushu (九州), typhoons usually occur about 3.2 times between July and September. The Mongols had been at sea and along Japan’s coast for around three months. So, they were likely to be hit by a typhoon sooner or later.

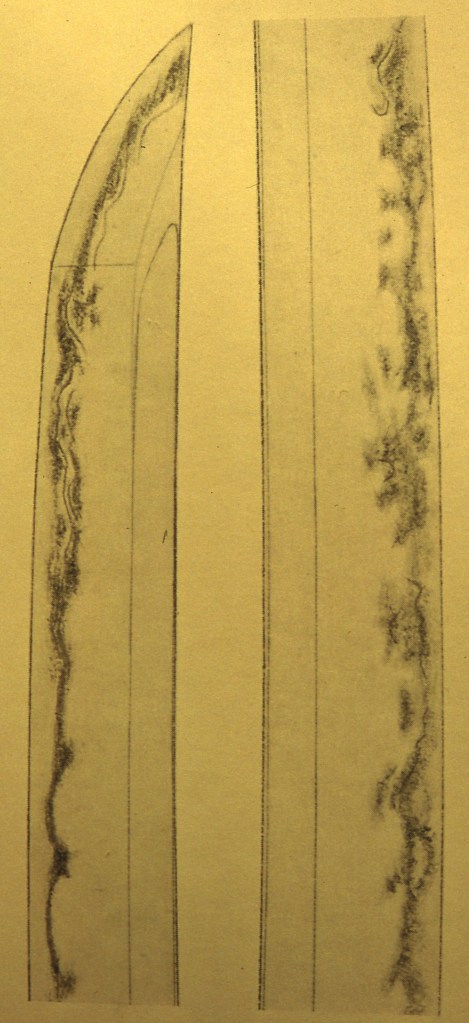

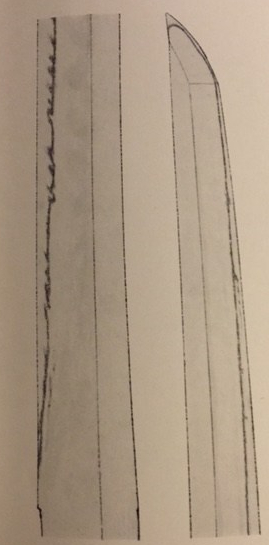

The Mongol Empire lost 2/3 of its naval forces during the event at Ko’an-no-eki. Even after the Mongols failed in two invasions, Kublai Khan still insisted on attacking Japan again, despite his advisers’ warnings not to. Ultimately, the plan was delayed and then terminated due to numerous rebellions and upheavals, and no lumber was left to build ships. Soon after, Kublai died in 1294. Historical records of the Mongols indicate that Mongolian officials highly praised Japanese swords. Some even suggest that one reason it was difficult to defeat Japan was because of its long, sharp swords. The experience of the Mongolian invasion changed the ikubi kissaki (猪首切先) sword into a new Soshu-den (相州伝) style. The next chapter describes this new style of sword, the Soshu-den swords.

The stone wall scene. Photo from Wikipedia. Public Domain

The stone wall scene. Photo from Wikipedia. Public Domain

* Number of soldiers by https://kotobank.jp/word/元寇-60419 . Referred to several different reference sources. They all have similar numbers of soldiers and ships.

The stone wall scene. Photo from Wikipedia. Public Domain

The stone wall scene. Photo from Wikipedia. Public Domain