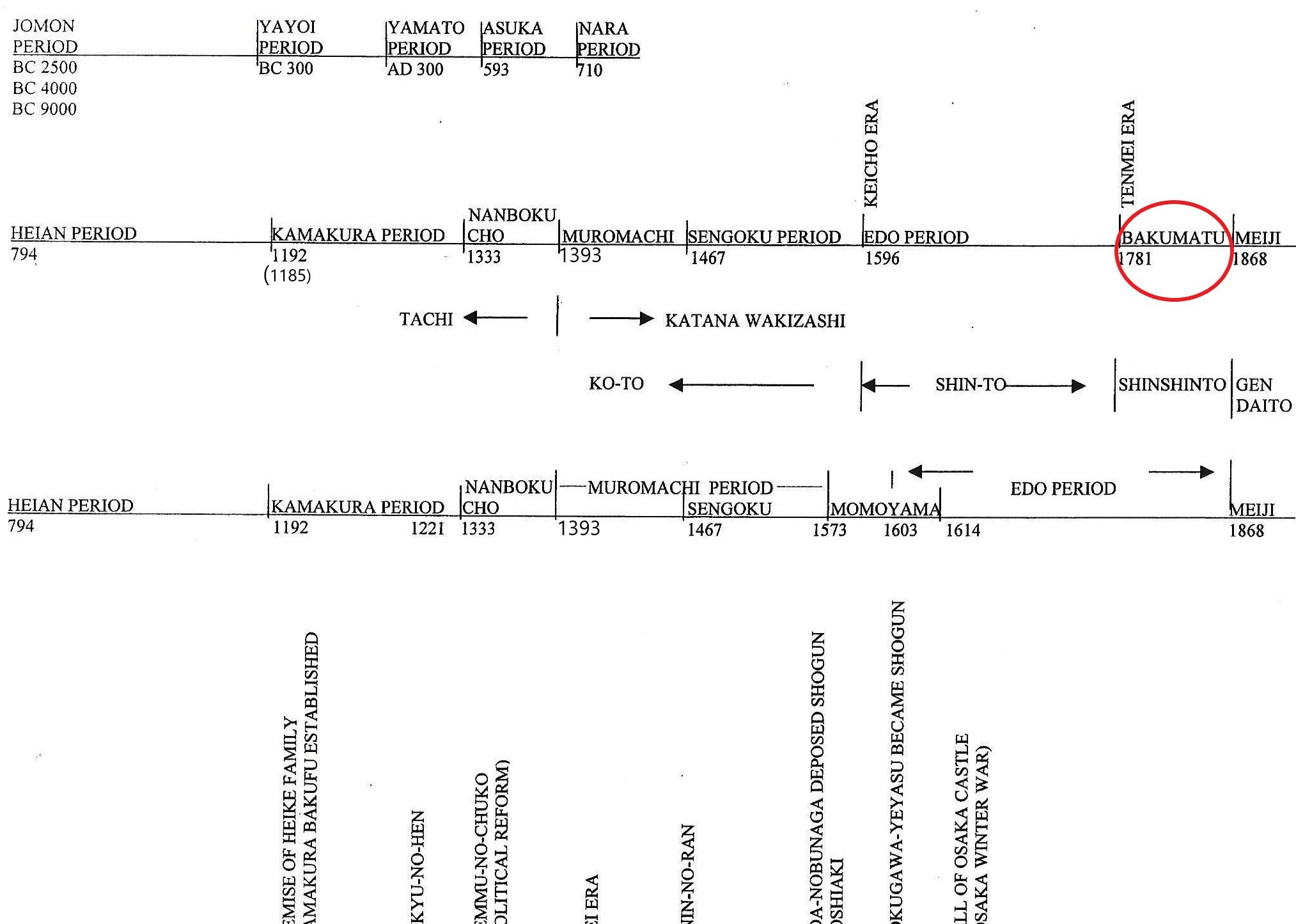

This chapter is a detailed part of Chapter 29, Bakumatu Period History. Please read Chapter 29 before reading this chapter.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The final period of the Edo period, roughly the Tenmei era (天明), from 1781 to 1868, is known as the Bakumatsu. During this period, Japan’s economy started to stagnate.

Several Tokugawa shoguns across generations attempted to implement financial reforms, each with some success, but none resolved the core economic problems.

The Tokugawa Bakufu mainly tried to impose fiscal restraint on the government, forcing people to lead frugal lives and even banning small luxuries. This only shrinks the economy and worsens the situation. Additionally, they raised the prevailing interest rate, believing it might resolve the problem. It was a typical non-economist solution. The interest rate should be lowered in situations like this. As a result, lower-level samurai became more impoverished, and farmers often revolted. Additionally, many natural disasters affected agricultural areas. The famous Kurosawa movie “Seven Samurai” was set around this time. As we all know, “Magnificent Seven” is a Hollywood version of “Seven Samurai.”

Gradually, a small cottage industry emerged alongside increased farming productivity, led by local leaders. Merchants became wealthier, and city residents grew richer. However, the gap between the rich and the poor widened. The problem of ronin (unemployed samurai) has become serious and almost dangerous to society.

The Edo Towns-people’s Culture

During this time, novels were also written for everyday people, not just for the upper class. In the past, paintings were associated with religion and were only accessible to the upper class. Now, they are for the general public.

The Bakumatsu period was a golden age for “ukiyo-e (浮世絵).” Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿1753-1800) was well-known for his portraits of women. Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎1760-1849) and Ando Hiroshige (安藤広重1797-1858) were famous for their landscape woodblock prints. Maruyama Okyo (円山応挙) painted using European perspective techniques. Katsushika Hokusai’s daughter also drew some of her paintings with perspective. Her name is “Ooi, 応為. ” Only a few of her works remain today. It is said that even her genius father was surprised by her drawing ability.

Although the number was small, some people learned Dutch. The Netherlands was one of only two countries allowed to enter Japan. These individuals translated a European medical book into Japanese using French and Dutch dictionaries, and they wrote a book titled “Kaitai Shinsho (解体新書).” Following this translation, books on European history, economics, and politics were translated. These books inspired new ideas and influenced intellectual thought.

Schooling thrived in society. Each feudal domain operated its own schools for the sons of the daimyo’s retainers. Townspeople’s children attended schools called terakoya (寺子屋: unofficial neighborhood schools) to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Pressure from the Outside World

Although Japan was under the Sakoku policy (鎖国: national isolation policy), people were aware of events outside Japan. Since the early 17th century, Russian messengers had come to Japan to demand trade (in 1792 and 1804). In 1808, English ships arrived in Nagasaki. In 1825, the Tokugawa bakufu ordered the firing of guns on any ships that came close to Japan. In 1842, following England’s victory in the Opium War against the Qing dynasty, the Bakufu decided to supply foreign ships with food and fuel. They feared facing the same fate as the Qing. In 1846, the U.S. sent a fleet commander to Japan to establish diplomatic relations, but the Bakufu refused. The U.S. needed Japan to open its ports to get supplies of food, water, and fuel for its whaling ships in the Pacific Ocean.

In 1853, Fleet Commander Perry* arrived at Uraga (浦賀: a port in Japan) with four warships, demonstrating American military power to open the country. The Tokugawa bakufu had no clear policy for handling such a situation and recognized that it was difficult to maintain the isolation policy any longer.

In 1854, the “Japan-U.S. Treaty of Amity and Friendship” was signed. After that, Japan made treaties with England, Russia, France, and the Netherlands. This ended more than 200 years of Sakoku (the national isolation policy), and Japan opened several ports to foreign ships.

However, these treaties caused many problems. The treaties were unfair, leading to shortages of everyday necessities; as a result, prices rose. Also, a large amount of gold flowed out of Japan. This was due to differences in the gold-to-silver exchange rate between Japan and Europe. In Japan, the exchange rate was 1 gold coin to 5 silver coins, whereas in Europe it was 1 gold coin to 15 silver coins.

In addition to these issues, there were more problems: who should succeed the current shogun, Tokugawa Yesada (徳川家定), since he had no heir. During this chaotic period, many feudal domains opposed one another, seeking a shogun whose political ideas aligned with their own. Many conflicts had already led to major battles among the domains, and there were additional reasons for them to oppose the bakufu.

Now, the foundation of the Tokugawa Bakufu has begun to fall apart. The Choshu-han (Choshu domain) and the Satsuma-han (Satsuma domain) were the main forces opposing the Tokugawa bakufu. At first, they opposed each other. However, after several tense incidents, they decided to reconcile and work together against the Bakufu, realizing it was not the time to fight among themselves. England, recognizing that the Bakufu no longer held much power, began to align more closely with the emperor’s side, whereas France sided with the Tokugawa. England and France almost went to war over Japan.

In 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu issued the “Restoration of Imperial Rule (Taisei Hokan, 大政奉還).” In 1868, the Tokugawa clan vacated Edo Castle, and the Meiji Emperor moved in. This site is now Kokyo (皇居: Imperial Palace), where the current Emperor resides.

Many prominent political figures actively participated in the overthrow of the Tokugawa bakufu. Among them are Ito Hirobumi (伊藤博文), Okubo Toshimichi (大久保利通), Shimazu Nariakira (島津斉彬), and Hitotsubashi Yoshinobu (一橋慶喜). They established a new system of government, the Meiji Shin Seifu (明治新 ), with the emperor at its core.

Today, the original Edo-jo (Castle) was destroyed by a large fire. However, the original moat, the massive stone walls, and a beautiful bridge called Nijyu-bashi (二重 橋, below) still remain. Large garden areas are open to the public. This area is famous for its beautiful cherry blossoms. The Imperial Palace is located in front of and within walking distance of the Marunouchi side of Tokyo Station.

Today, Japanese people enjoy historical dramas set during the Meiji Ishin (Restoration), and we often see these on TV and in movies. These stories feature Saigo Takamori (西郷隆盛), Sakamoto Ryoma (坂本龍馬), and the Shinnsen-gumi (新撰組). Although fictional, the film The Last Samurai is set during this period, featuring Saigo Takamori.

Imperial Palace (From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository ).

*Perry

Commodore M.C. Perry visited Japan twice with four warships. In 1853, he carried a sovereign diplomatic letter from the President of the U.S. The following year, he returned to demand a response to the letter. After the expedition, Perry wrote a book about his journey, “Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, Under the Command of Commodore M.C. Perry, United States Navy by Order of the Government of the United States.” In this book, he describes Japan very favorably —its beautiful scenery, the ingenuity of its people, and the lively, active women — through his drawings.

Although it was a long, tough negotiation between the Edo Bakufu and Perry, there were several enjoyable moments. Perry gifted Japan a 1:4-scale model steam locomotive, a sewing machine, and more. The Japanese arranged a sumo match and offered gifts, such as silk, lacquerware, and other items. The Japanese prepared elaborate banquets for the American diplomats, and Perry invited Japanese officials to his feast. The highlight was when Perry served a dessert at the end of the dinner. Perry printed each guest’s family crest on a small flag and placed it on the dessert.

Before starting his expedition, he expected tough negotiations ahead. Therefore, he researched what the Japanese would enjoy and found that they enjoyed parties a lot. He brought skilled chefs and loaded the ship with livestock for future parties. He entertained Japanese officials with whiskey, wine, and beer. Initially, the U.S. wanted Japan to open five ports, while the Bakufu was willing to open only one. Ultimately, both sides agreed to open three ports.

File:Commodore-Perry-Visit-Kanagawa-1854.jpg From ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/黒船 Public Domain

File:Commodore-Perry-Visit-Kanagawa-1854.jpg From ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/黒船 Public Domain