This chapter is a detailed section of Chapter 11, Ikubi-kissaki, and continues from Chapter 44|Part 2 of 11 Ikubi-kissaki Sword. Please read Chapter 11 and Chapter 44 before proceeding with this section.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section.

Bizen Saburo Kunimune (備前三郎国宗)

Another swordsmith worth mentioning in this section is Bizen Saburo Kunimune (備前三郎国宗). During the middle Kamakura period, the Hojo clan invited top swordsmiths to Kamakura. Awataguchi Kunitsuna (粟田口国綱) from Yamashiro in Kyoto, Fukuoka Ichimonji Sukezane (福岡一文字助真) from the Bizen area, and Bizen Kunimune (備前国宗) from the Bizen area moved to Kamakura with their circle of people. These three groups started the Soshu-den (相州伝). Refer to Chapter 14, Late Kamakura Period Swords.

- Sugata (shape) ——————— Ikubi-kissaki style. Sometimes Chu-gissaki. Thick body. Koshi-zori. Narrow Shinogi width.

- Horimono (Engravings) —————- Often narrow Bo-hi (single groove)

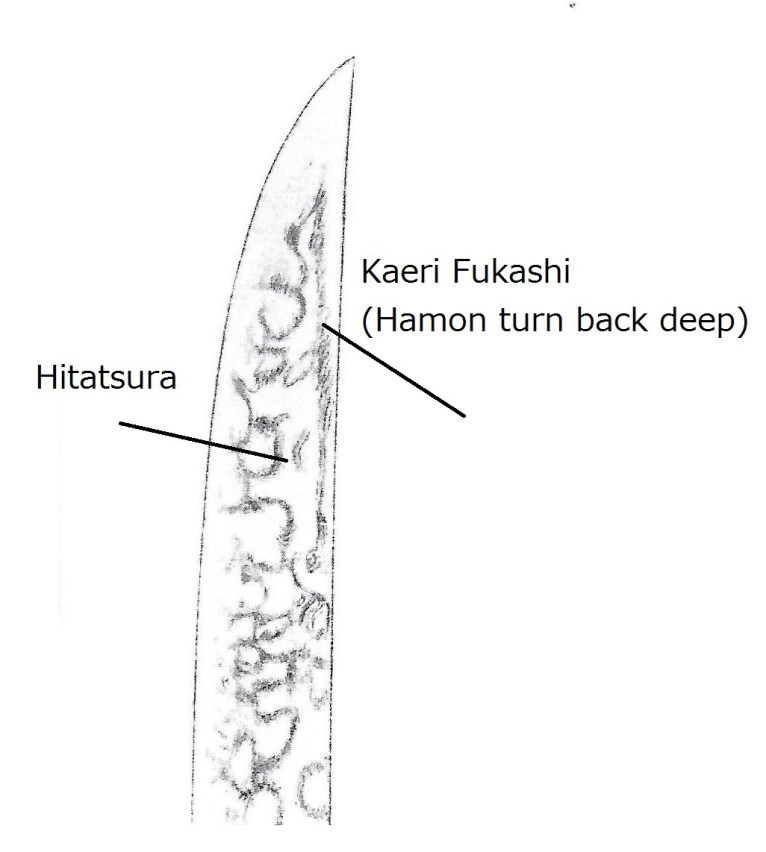

- Hamon (Tempered line) ————- O-choji Midare (irregular large clove shape) with Ashi. Or Ko-choji Midare (irregular small clove shape) with Ashi. Nioi base with Ji-nie (Nie in the Hada area). Some Hamon appear squarish with less Kubire (less narrow at the bottom of the clove). Hajimi (刃染み rough surface) may show. The Kunimune swords often show a lower part with Choji and an upper part with less activity without Ashi.

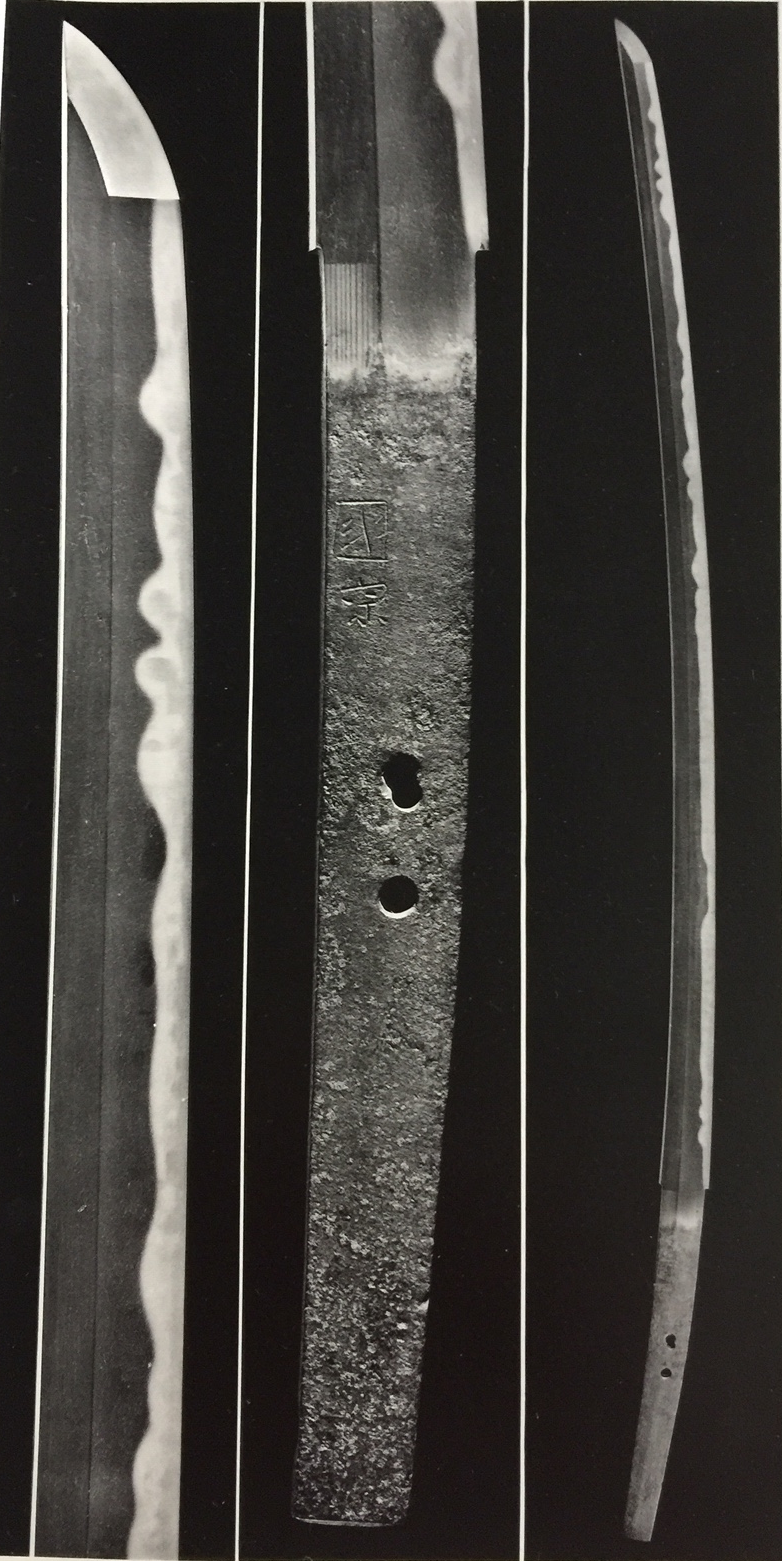

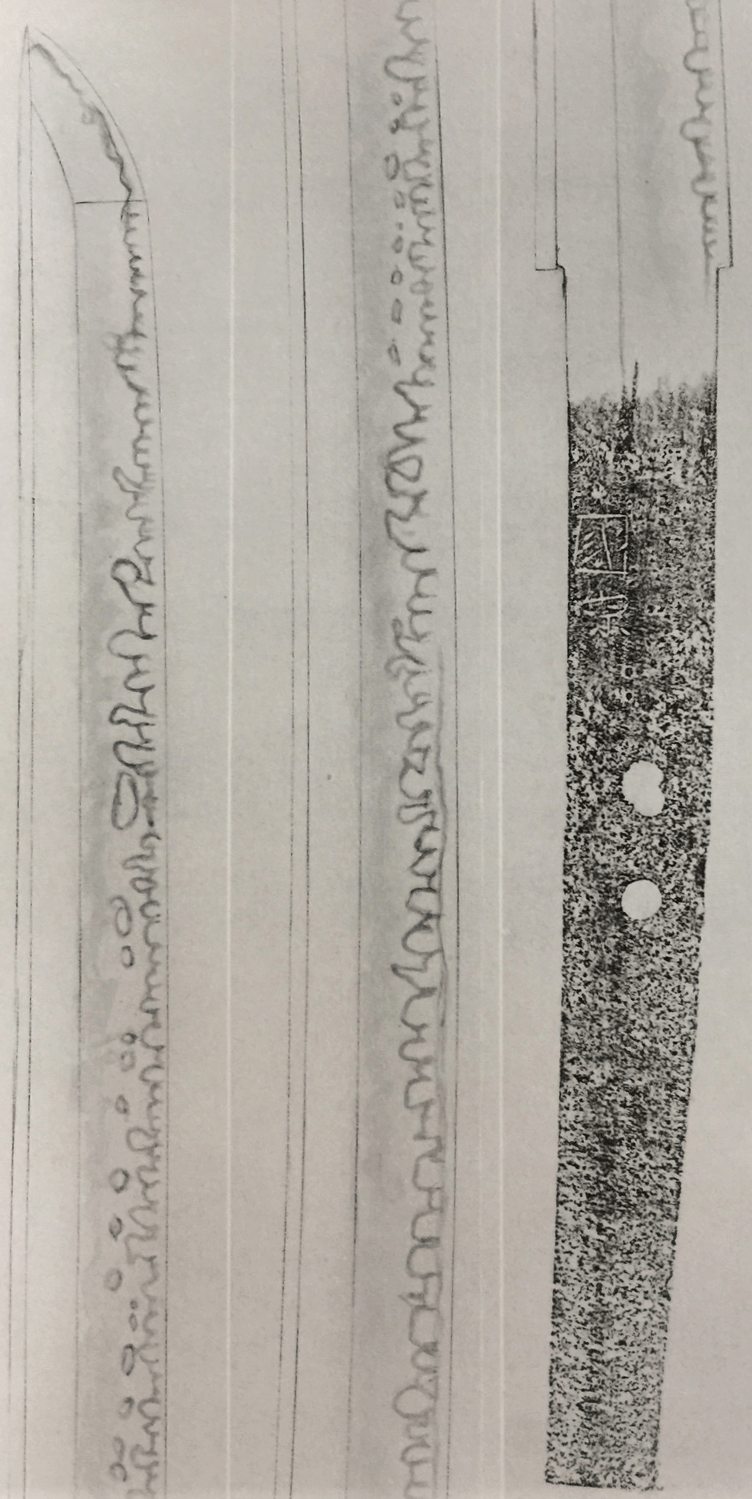

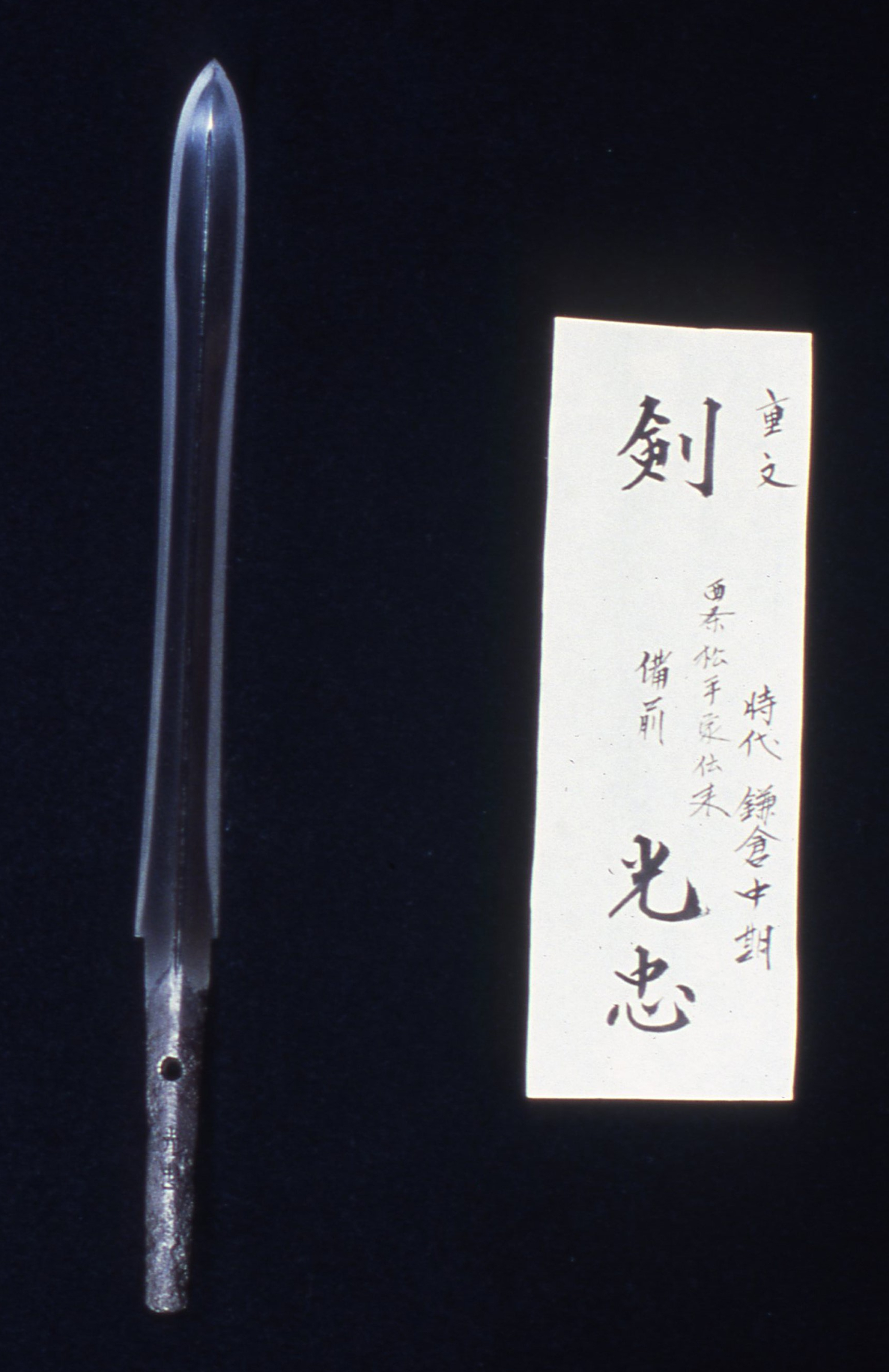

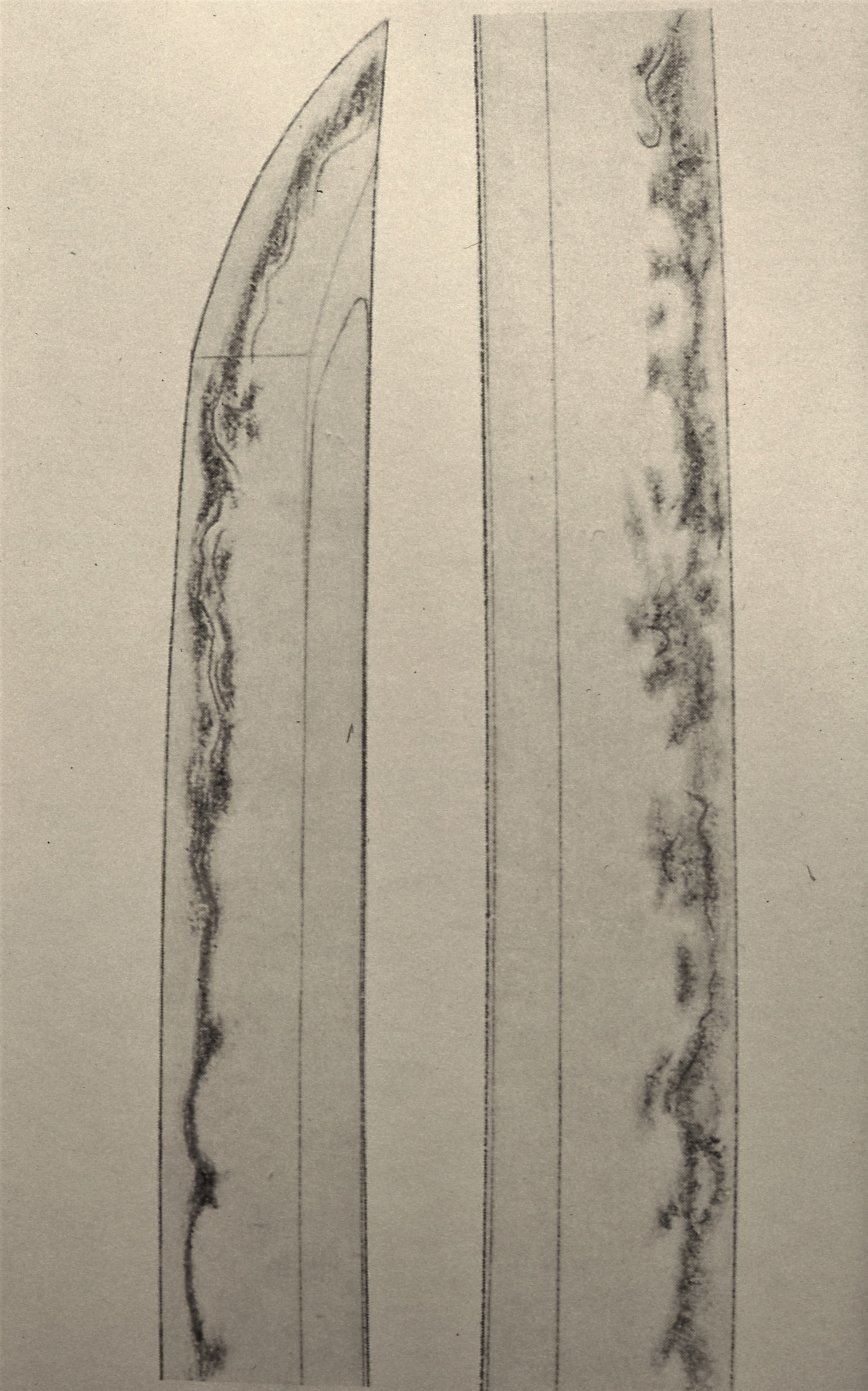

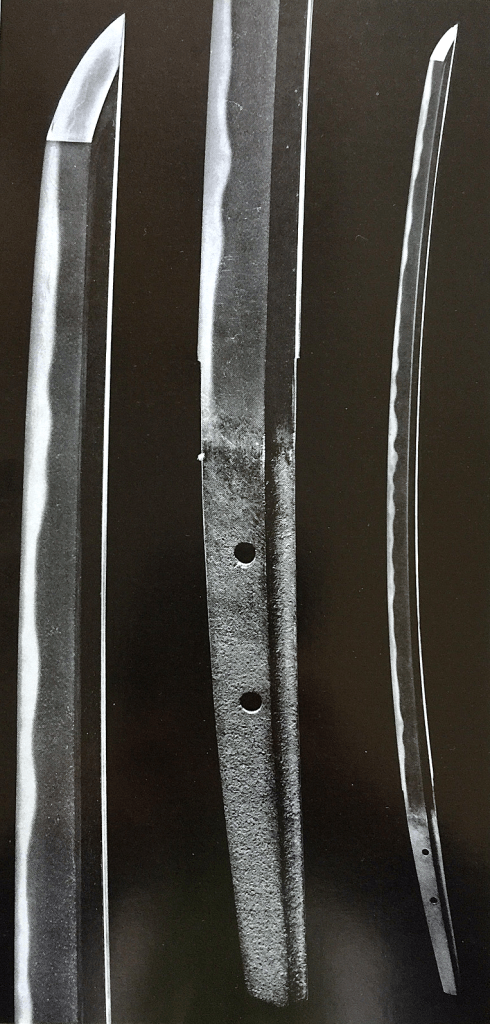

Bizen Saburo Kunimune (備前三郎国宗) Photo from “Nippon-to Art Sword of Japan, ” The Walter A. Compton Collection. National Treasure

Bizen Saburo Kunimune (備前三郎国宗) Photo from “Nippon-to Art Sword of Japan, ” The Walter A. Compton Collection. National Treasure

- Boshi ———————— Small irregular. Yakizume or short turn back.

- Ji-hada —————-Wood-grain pattern. Fine Ji-hada with some Ji-nie (Nie inside Ji-hada). Midare-utsuri (irregular shadow) is visible. A few Hajimi (rough surface).

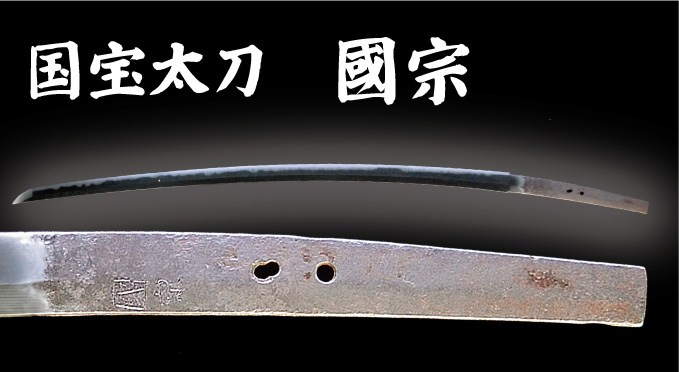

The above photo is from the official website of the Terukuni Jinja Shrine in Kyushu. http://terukunijinja.pkit.com/page222400.html

The above photo is from the official website of the Terukuni Jinja Shrine in Kyushu. http://terukunijinja.pkit.com/page222400.html

This is the national treasure, Kunimune, preserved at the Terukuni Jinja Shrine in Kagoshima Prefecture. See the photos on the previous page. This Kunimune sword was lost after WWII. Dr. Compton, chairman of the board at Miles Laboratories in Elkhart, Indiana, found it in an antique shop in Atlanta. I mentioned Dr. Compton in Chapter 32, Japanese Swords, after World War II. When he saw this sword, he realized it was not just an ordinary sword. He bought it and inquired at the Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai (The Japanese Sword Museum) in Tokyo. It turned out to be the famous missing national treasure, Kunimune, from the Terukuni Jinja shrine. He returned the sword to the shrine without compensation in 1963.

My father became close friends with him around this time through Dr. Homma and Dr. Sato, both leading sword experts. Later, Dr. Compton asked Dr. Honma and my father to examine his collection of swords at his house, where he had many, as well as those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. My father wrote about this trip and the swords he examined in those museums and published a book in 1965 titled “Katana Angya (刀行脚).”

For Dr. Compton and my father, those days must have been the best times of their lives. Their business was doing well, and they could spend a lot of time on their interests and enjoy themselves. It was also the best time for me. One time, when I visited Compton’s house, he spent hours showing me his swords in the basement for hours, nearly all day. His house was large, and the basement, which he had built as his study, had a fire prevention system. The lighting system was perfect for viewing swords and other art objects.

His wife, Phoebe, told him he shouldn’t keep a young girl (I was a college student at the time) in the basement all day. He agreed and took me to his cornfield to pick some corn for dinner. From a basement to a cornfield, not much of an improvement? So, Phoebe decided to take me shopping and have lunch in Chicago. Good idea, but it was too far. Compton’s house was in Elkhart, Indiana. The distance between Elkhart and Chicago was about 2.5 hours by car. It was too far just for shopping and lunch. To my surprise, the company’s employee flew us to the rooftop of a department store, we did some shopping, had lunch, and then flew back.

Miles Laboratories and a well-known Japanese large pharmaceutical company had a business partnership at that time. Dr. Compton frequently traveled to Japan for business purposes. However, whenever he visited Japan, he spent days with sword people, including my father, and I usually followed him. One of the female workers’ jobs at this pharmaceutical company was to translate the sword book into English.

My parents’ house was filled with Miles’ products. Miles Laboratories had a large research facility in Elkhart, Indiana. I visited there several times. One day, I sat with Dr. Compton in his office, looking into a sword book with our heads close together. That day, movie actor John Forsythe visited the research lab. He was the host of a TV program sponsored by Miles Laboratories. All the female employees were making a big fuss over him. Then he entered Dr. Compton’s room to greet him, expecting the chairman to be sitting in his big chair at his desk, looking like a chairman. But he saw Dr. Compton looking into the sword book seriously, with his head against mine. Dr. Compton’s appearance was just like that of any chairman of the board of a major company, as one might imagine, and I was a Japanese college student looking like a college student. John Forsythe showed a strange expression as if he did not know what to think.

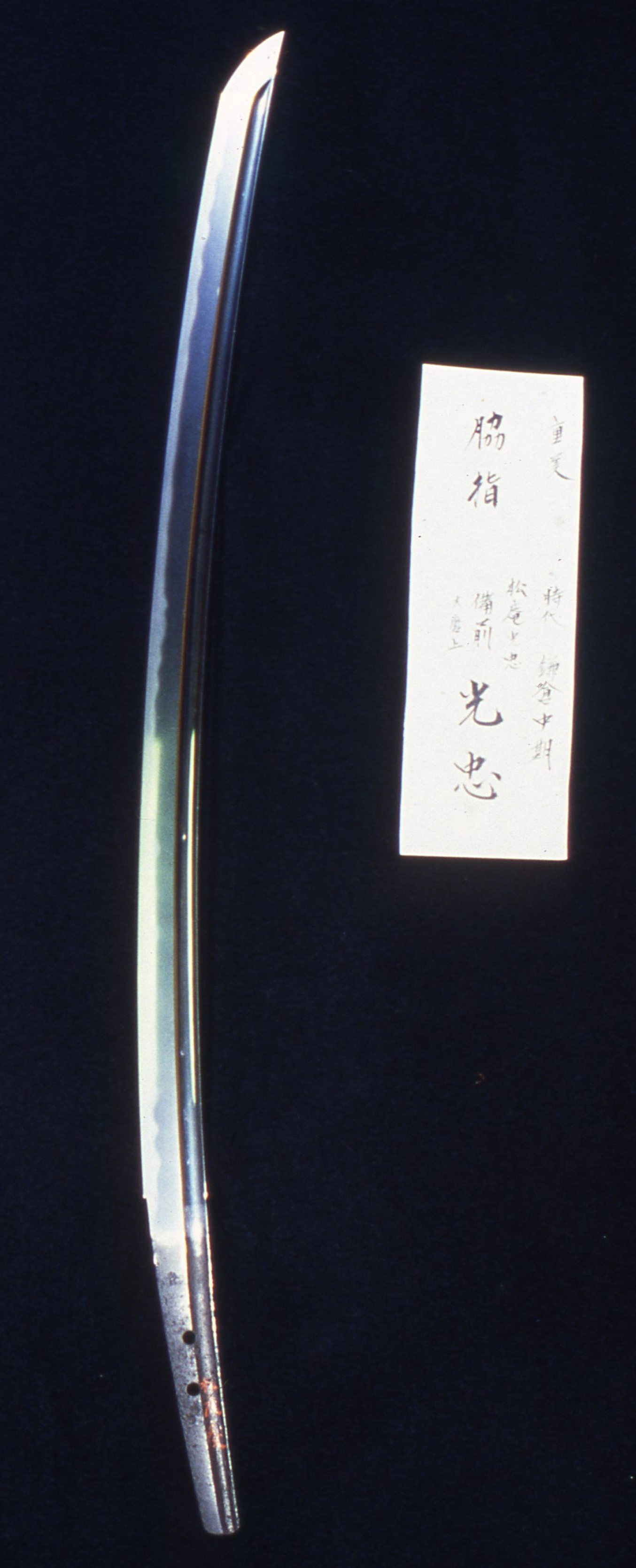

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bukazai) Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bunakzai)

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bukazai) Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bunakzai)

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Token) Osafune Mitsutada(Juyo Bunkazai)

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Token) Osafune Mitsutada(Juyo Bunkazai)

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)