The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section.

After Jokyu-no-ran (Chapter 10 Jokyu-no-ran), the power of the Imperial Court declined significantly. The successor, the Hojo clan, which was a dominant force during the Kamakura period, also began to face financial difficulties and began to lose control over regional lords. One reason was the costs incurred by the Mongol invasion. The Kamakura bakufu (government) could not adequately reward the samurai who fought hard during the war. As a result, they became very dissatisfied with the bakufu. Seeing this as an opportunity, Emperor Go-Daigo attempted to attack the Kamakura bakufu twice but failed both times. He was exiled to Oki Island. In the meantime, Ashikaga Takauji (足利尊氏) and several groups of anti-Kamakura samurai gathered armed forces and succeeded in destroying the Kamakura bakufu in 1333. This war ended the Kamakura period.

Emperor Go-Daigo, who had been exiled to Oki Island, returned to Kyoto and attempted political reforms. This reform was known as Kenmu-no-chuko (or Kenmu-no-shinsei, 建武の中興). However, his reforms failed to satisfy most of the ruling class. Seeing an opportunity, Ashikaga Takauji attacked the Imperial Court in Kyoto, deposed Emperor Go-Daigo, and installed a member of a different branch of the Imperial family as emperor.

Emperor Go-Daigo, however, insisted on his legitimacy, moved to Yoshino in the south of Kyoto, and established another Imperial court. Thus, the Northern and Southern Dynasties began. With much strife between these rival courts and internal problems within each court, more samurai groups began to move to the Northern Dynasty. About sixty years later, the Southern Dynasty was forced to accept the Northern Dynasty’s proposal. Consequently, the Northern Dynasty became the legitimate imperial court. This sixty-year period is referred to as the Nanboku-cho or Yoshino-cho period.

During the Nanboku-cho period, samurai preferred longer, more elaborate, yet practical swords. The Soshu-den was at the height of its prominence. However, the Soshu group was not the only one to produce Soshu-den-style swords. Other schools and provinces in different areas also made Soshu-den-style swords.

Late Kamakura Period Swordsmiths (Early Soshu-Den time)

- Tosaburo Yukimitsu (藤三郎行光)

- Goro Nyudo Masamune (五郎入道正宗)

- Hikoshiro Sadamune (彦四郎貞宗)

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Nanboku-cho Period Swordsmiths (Middle Soshu-Den time)

- Hiromitsu (広光)

- Akihiro (秋広)

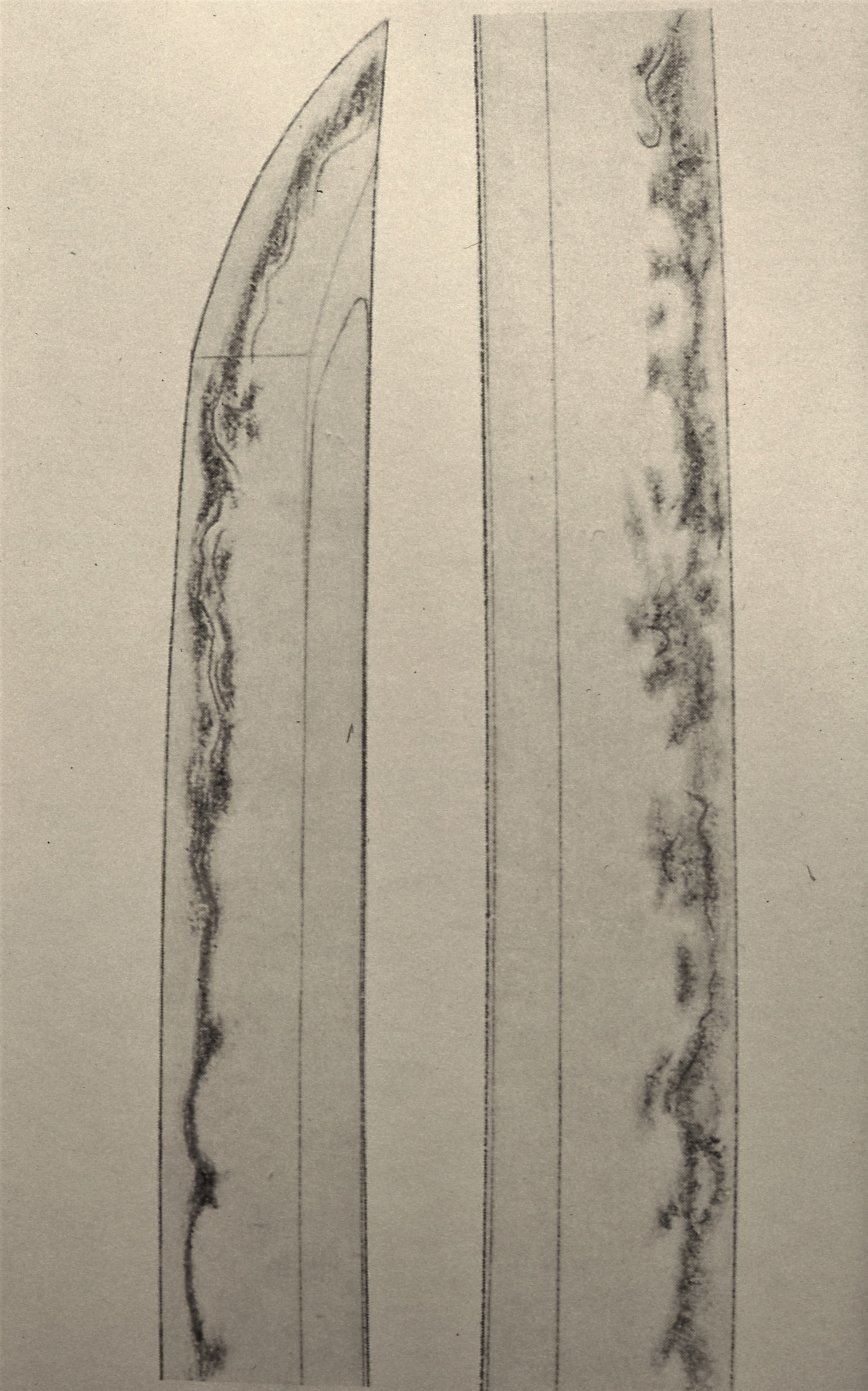

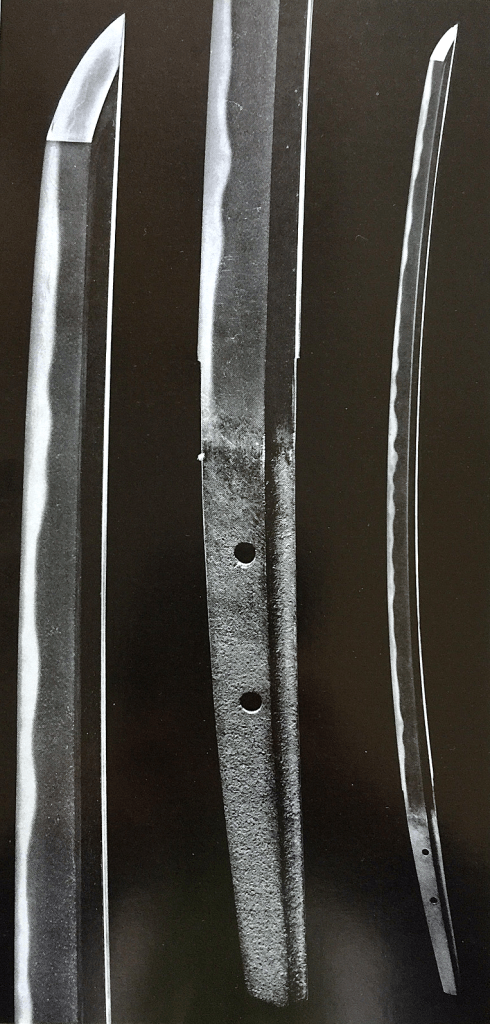

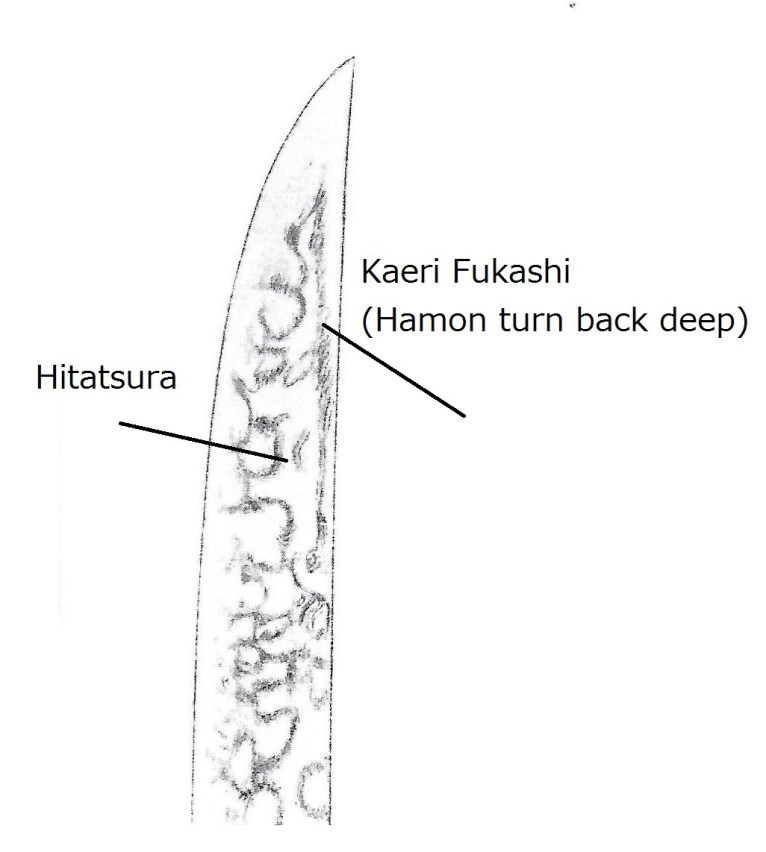

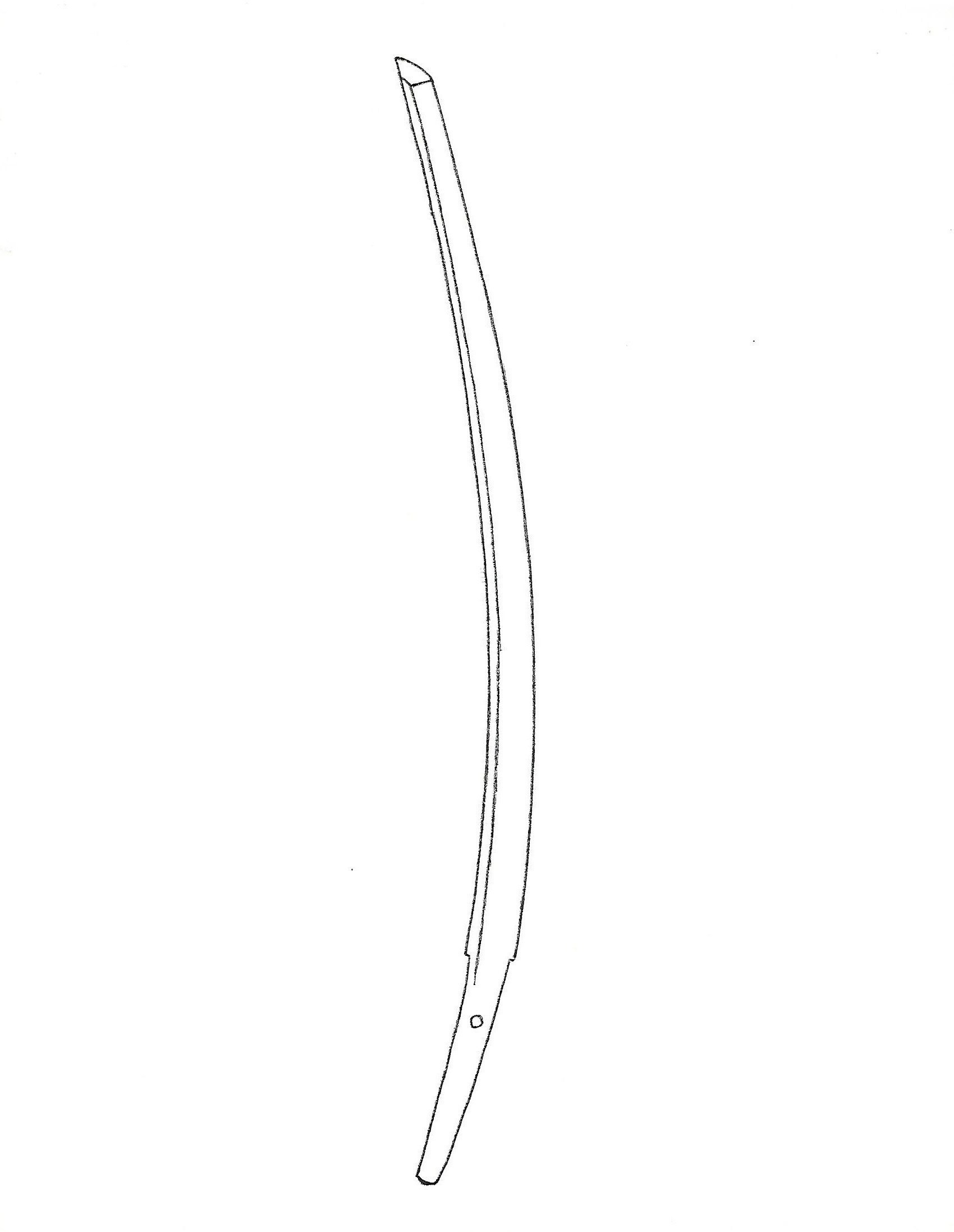

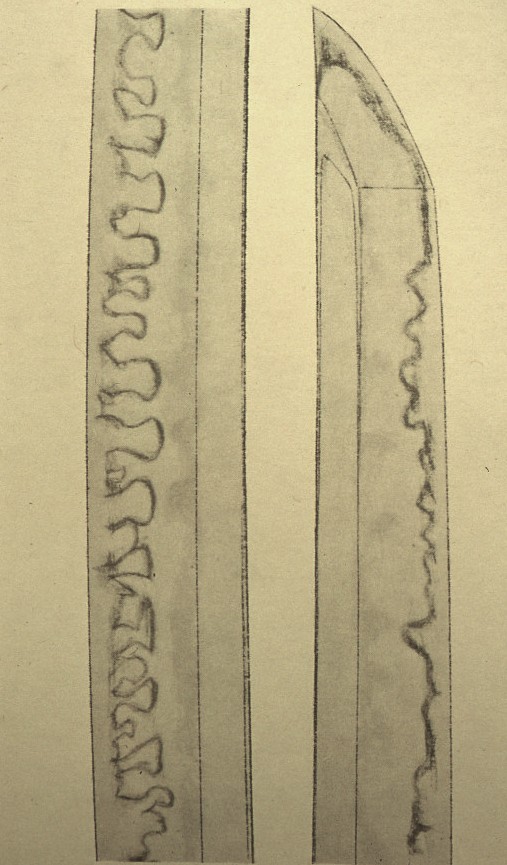

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Muromachi Period Swordsmiths (Late Soshu-Den time)

- Hiromasa (広正)

- Masahiro (正広)

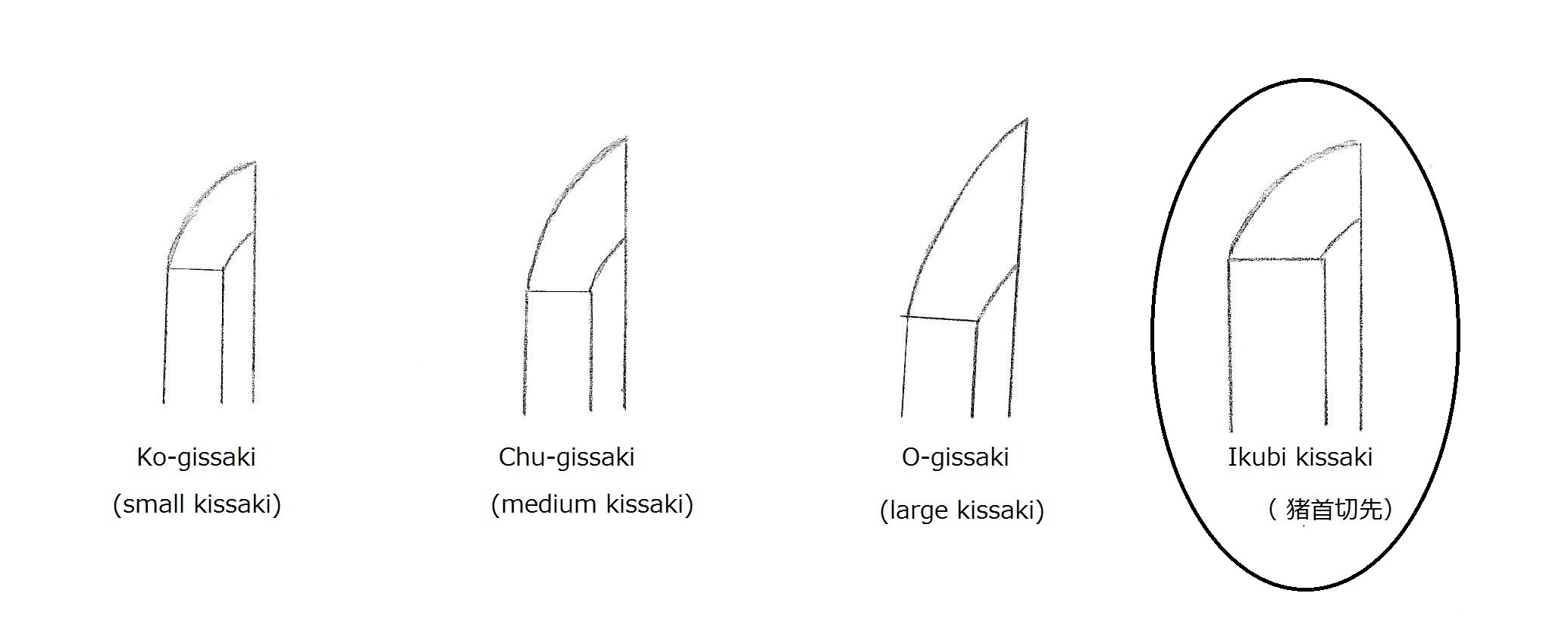

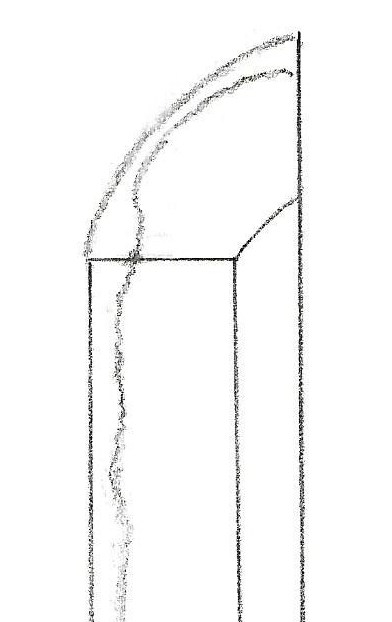

Kawazuko-choji O-choji Ko-choji Suguha-choji (tadpole head) (large clove) (small clove) (straight and clove)

Kawazuko-choji O-choji Ko-choji Suguha-choji (tadpole head) (large clove) (small clove) (straight and clove)

Sansaku-boshi

Sansaku-boshi

Osafune Nagamitsu(長船長光) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Osafune Nagamitsu(長船長光) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

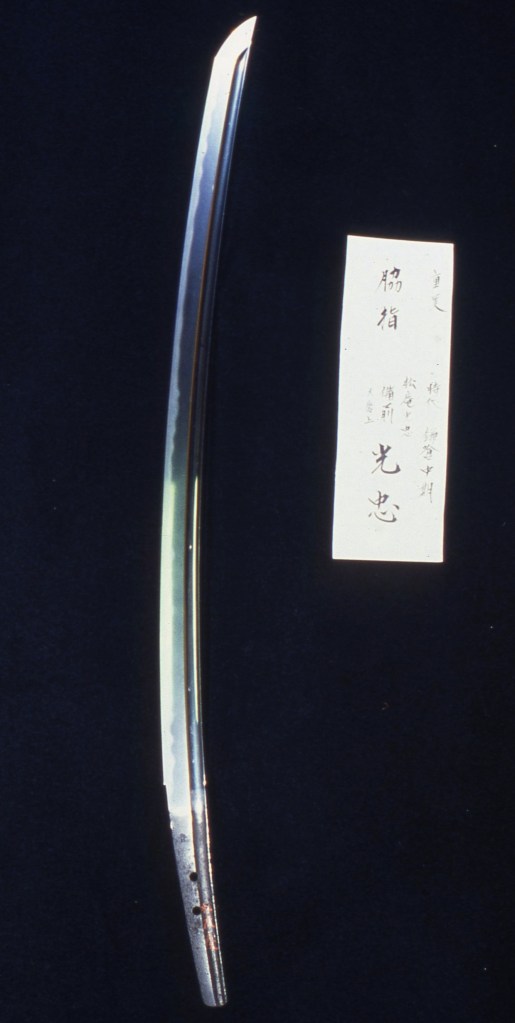

Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠) Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠)

Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠) Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠)

The tomb of Minamoto-no-Yoritomo. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.

The tomb of Minamoto-no-Yoritomo. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.