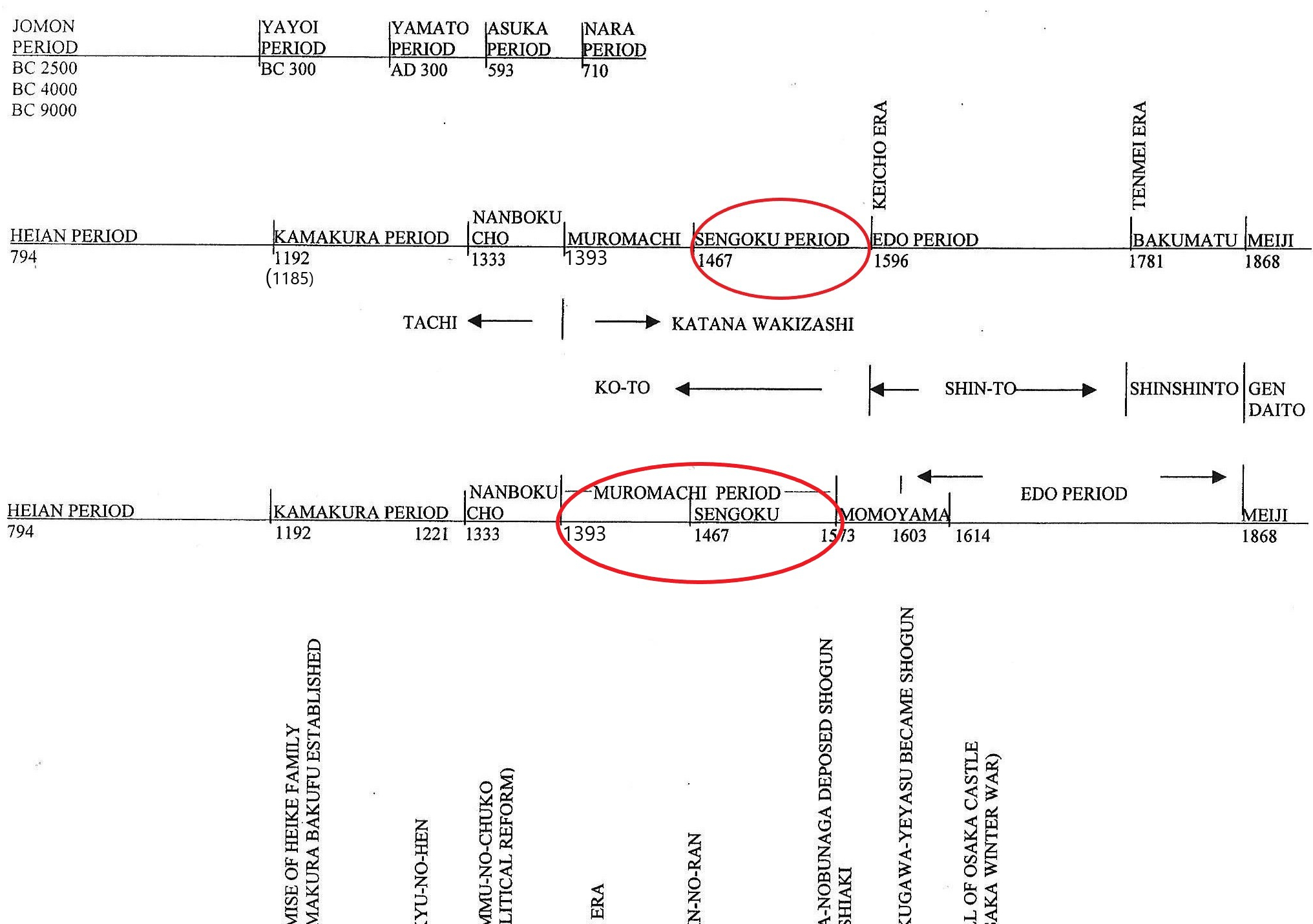

Chapter 61 is a detailed part of Chapter 27, Shinto Main 7 Regions (part A). Please read Chapter 27 before reading this section.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

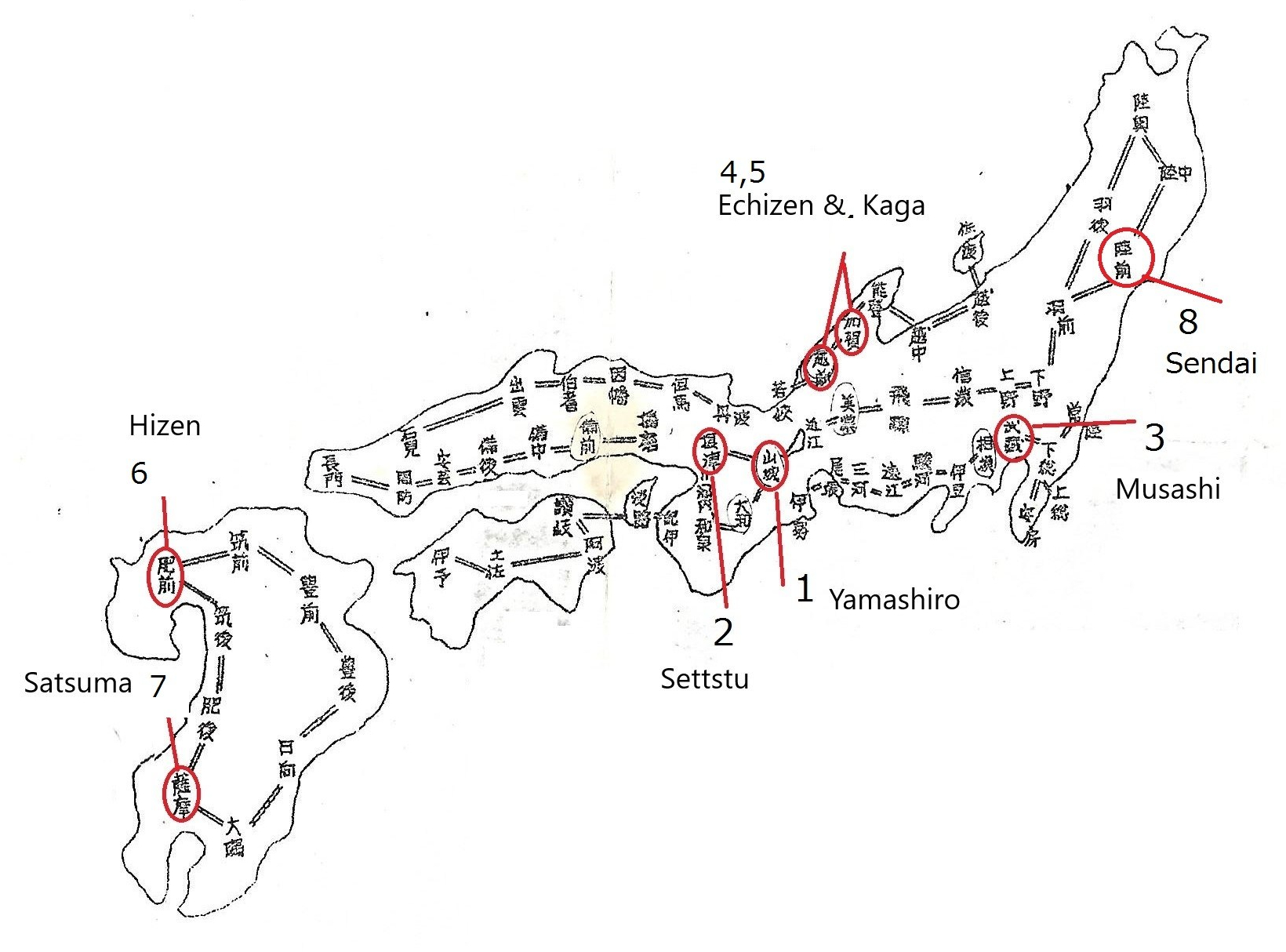

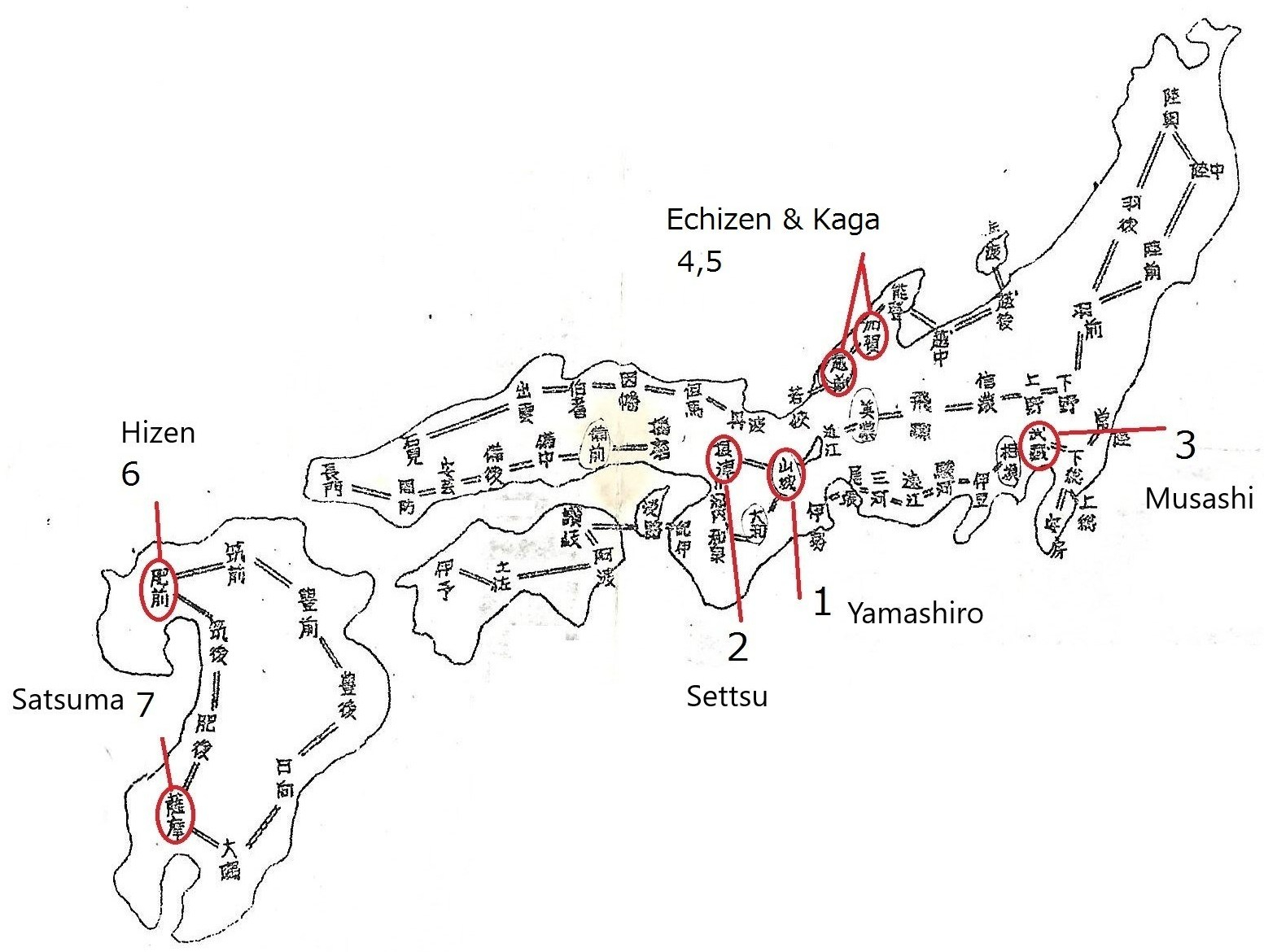

Chapter 27, Shin-to Main 7 Regions (Part A), and Chapter 28, Shin-to Main 7 Regions (Part B), describe an overview of the seven main regions. This chapter and the next chapter show photos of representative swords from these regions. They are Yamashiro (山城, in Kyoto), Settsu (摂津, today’s Osaka), Musashi (武蔵, Edo), and Satsuma (薩摩, Kyushu). However, Echizen (越前), Kaga (加賀), and Hizen (肥前) are omitted.

With ko-to swords, features such as the condition of the hamon, kissaki size, length, and shape of the nakago, etc., indicate when the sword was made. During the ko-to period, Bizen swordsmiths produced Bizen-den swords, Yamashiro swordsmiths made Yamashiro-den swords, and Mino swordsmiths made Mino-den swords. However, during the shin-to period, that is not the case. The den and the swordsmith’s location often do not match. For shin-to swords, we study the swordsmiths and swords from the seven main regions along with their characteristics.

Regarding swords made during the ko-to period, if a sword has a wide hamon line with nie, usually, its ji-hada shows a large wood grain or a large burl grain. Also, when you see a narrow hamon line, it typically features a fine ji-hada.

However, with shin-to swords, if a sword shows a wide hamon with nie, it often has a small wood grain or small burl grain pattern on ji-hada. If it has a narrow hamon line, it may have a large wood grain pattern on the ji-hada. This is a shin-to characteristic.

Here is an exception: some early Soshu-den swords from the late Kamakura period may show a wide hamon with nie, which has small burls on the ji-hada. Because of that, whether it is ko-to or shin-to can be confusing. Even so, other features such as ji-hada or other parts should indicate whether it is shin-to or ko-to.

Yamashiro (山城: Kyoto)

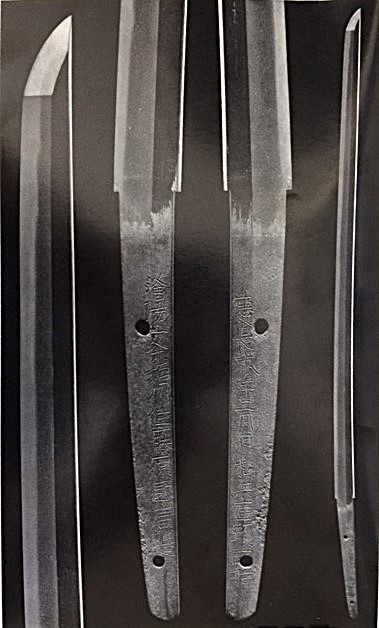

Horikawa Kunihiro (堀川国広) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Horikawa Kunihiro (堀川国広) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Horikawa Kunihiro (堀川国広)

Horikawa Kunihiro was regarded as a master swordsmith among shin-to swordsmiths. He forged swords in many styles with various characteristics. The hamon types are o-notare, o-gunome, togari-ba (pointed hamon), chu-suguha with hotsure (frayed look), hiro-suguha with a sunagashi effect, inazuma, and kinsuji. Kunihiro preferred to shape his swords to resemble an o-suriage (shortened Nanboku-cho style long sword). Kunihiro‘s blades give a powerful impression. Kunihiro‘s swords often feature beautiful carvings; designs include dragons, Sanskrit letters, and more. Because he created swords in many different styles, there is no general characteristic that defines his work other than the hamon mainly being nie. His ji-hada is finely forged.

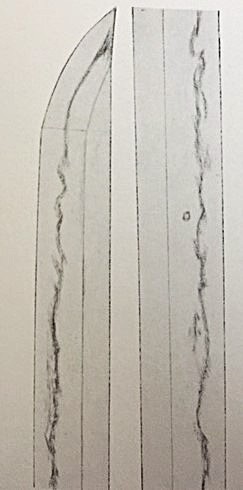

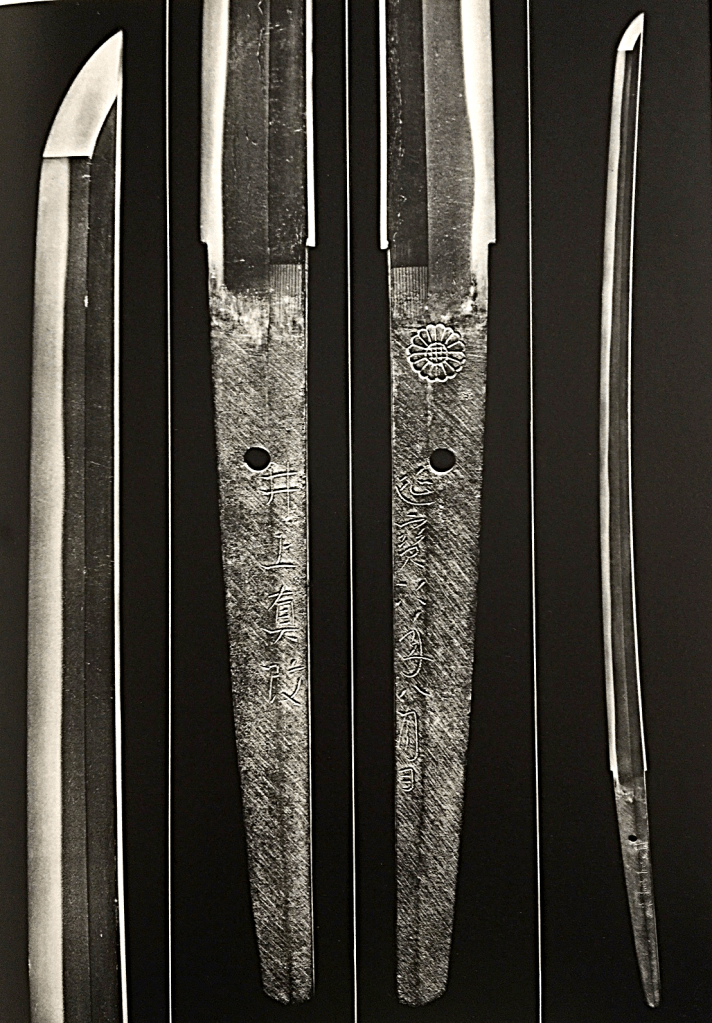

Iga-no-Kami Kinnmichi (伊賀守金道) Dewa Daijyo Kunimichi (出羽大掾国路) Both Juyo Token (重要刀剣), once my family owned, photos were taken by my father.

Iga-no-Kami Kinnmichi (伊賀守金道) Dewa Daijyo Kunimichi (出羽大掾国路) Both Juyo Token (重要刀剣), once my family owned, photos were taken by my father.

Iga-no-Kami Kinmichi ( 伊賀守金道)

The Kinmichi family is called the Mishina group. Refer to 27 Shinto Main 7 Regions Part A. Iga-no-Kami Kinmichi was awarded the Japanese Imperial chrysanthemum crest.

The characteristics of Kinmichi ——– Wide sword, shallow curvature, an extended kissaki, sakizori (curvature at 1/3 top), a wide tempered line, kyo-yakidashi (see 27 Shinto Main 7 Regions A ), hiro-suguha (wide straight hamon), o-notare (large wavy), yahazu-midare, hako-midare (refer to 24 Sengoku Period Tanto). Mishina-boshi, refer to 27 Shin-to Main 7 Regions A. Fine wood burl, masame appear in the shinogi-ji area.

Dewa Daijo Kunimichi (出羽大掾国路)

Dewa Daijo Kunimichi was the top student of Horikawa Kunihiro. The right photo above. Like Kunihiro, the sword resembles a shortened Nanboku-cho sword. Shallow curvature, a wide body, a somewhat elongated kissaki, and fukura-kareru (less arch in fukura). Wide tempered lines, large gunome, nie with sunagashi, or inazuma shows. Double gunome (two gunome side by side) appears. Fine ji-hada.

- Settu (摂津) Osaka (大阪 )

Settu (Osaka) is home to many famous swordsmiths. They are Kawachi-no-Kami Kunisuke (河内守国助), Tsuda Echizen-no-Kami Sukehiro (津田越前守助広), Inoue Shinkai (井上真改), and Ikkanshi Tadatsuna (一竿子忠綱), among others. The main characteristic of the Settsu (Osaka) sword ——– The surface is beautiful and fine, almost like a solid surface with no pattern or design. The two photos below are of the Settsu sword.

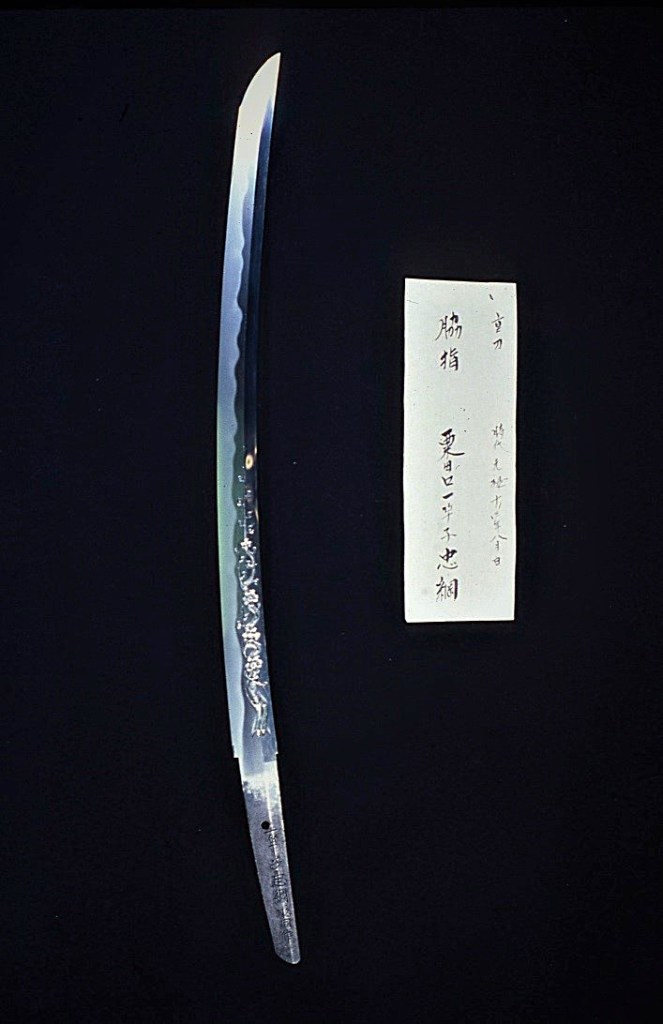

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna from the Sano Museum Catalogue. Permission granted to use.

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna from the Sano Museum Catalogue. Permission granted to use.

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna (一竿子忠綱)

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna was famous for his carvings. His father was also a well-known swordsmith, Omi-no-Kami Tadatsuna (近江守忠綱). Consequently, he was known as Awataguchi Omi-no-Kami Fujiwara Tadatsuna (粟田口近江守藤原忠綱), as shown in the nakago photo above.

The characteristics of Ikkanshi Tadatsuna ——-A longer kissaki and a wide-tempered line with nie. The Osaka yakidashi (transition between the suguha above machi and midare is smooth. Refer to 27 Shin-to Sword – Main 7 Regions (Part A) for details on Osaka yakidashi. O-notare with gunome, komaru-boshi with a turn back, and very fine ji-hada with almost no pattern on the surface.

Inoue Shinkai (井上真改) from “Nippon-to Art Swords of Japan” The Walter A. Compton Collection

Inoue Shinkai (井上真改) from “Nippon-to Art Swords of Japan” The Walter A. Compton Collection

Inoue Shinkai (井上真改)

Inoue Shinkai was the second generation of Izumi-no-Kami Kunisada (和泉守国貞), who was a student of Kunihiro. The characteristic of Inoue Shinkai’s swords —————- Osaka yakidashi, the tempered line gradually widens toward the top. O-notare and deep nie. Very fine ji-hada with almost no surface design.