This chapter is a detailed part of Chapter 17|Nanboku(Yoshino) Cho Period History (1333-1392). Please read Chapter 17 before reading this section.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The Nanboku-cho period (1333 – 1392) was between the fall of the Kamakura bakufu and the beginning of the Muromachi bakufu. It was a time when the Northern and Southern Dynasties coexisted. Around the time of the Mongolian invasion, Emperor Go-saga died without naming a successor. Because of that, his two heirs and their family lines, the Daigakuji-to (大覚寺統) and the Jimyoin-to (持明院統), alternately assumed the imperial position after Emperor Go-saga‘s death. This system was politically unstable. Additionally, many inconvenient problems arose; for example, while one emperor was still very young, the next-in-line emperor died young from a head injury while playing on a slippery stone.

At a time like this, Go-daigo (後醍醐天皇) became the emperor. He was placed on the throne as a temporary emperor until the young emperors reached maturity. Around this time, the emperors’ power was declining. The Kamakura bakufu (government) controlled the emperors. After the Mongolian invasion, even though typhoons drove the Mongolian troops away, the Kamakura bakufu faced financial troubles due to the costs of war. Many samurai who fought during the Mongolian invasion did not receive any rewards or compensation for their expenses and were also financially troubled. All these problems piled up and caused the resentment against the Kamakura bakufu.

Emperor Go-Daigo refused to be merely a placeholder emperor. He decided to stay as emperor and attack the Kamakura bakufu. For some reason, the Kamakura bakufu found out about his plans. Emperor Go-Daigo somehow managed to avoid being accused of being the instigator. Afterwards, the Kamakura bakufu appointed another heir for the next emperor. However, Go-Daigo insisted on remaining emperor. He planned another attack once more. This time, he had carefully planned and allied with prominent, powerful temples in Yamato (Nara today) since the Kamakura bakufu did not control them. Refer to 15 Revival of Yamato Den (大和伝復活) and 49 Part 2 of– 15 The Revival of Yamato Den.

This time again, the rebellion plot came to light. Go-Daigo sneaked out of Kyoto and fought against the Kamakura army. Although Go-Daigo’s army had fewer soldiers than the Kamakura army, several groups opposing the Kamakura bakufu rose up in various parts of Japan. Eventually, Go-Daigo was captured and sent to Oki Island (the same place where Emperor Go-Toba was exiled).

Even after exiling Emperor Go-Daigo to Oki Island, the Kamakura bakufu still had to fight against other uprising groups. One of the most famous rebels was Kusunoki Masashige (楠正成). Go-Daigo’s son also actively fought against the Kamakura bakufu and managed to ally with more factions.

More and more people sought to overthrow the Kamakura bakufu. Even Ashikaga Takauji (足利尊氏), one of the top men of the Kamakura bakufu who fought against Emperor Go-Daigo, betrayed the Kamakura and switched sides, becoming the emperor’s ally. Meanwhile, Go-Daigo escaped from Oki Island. More and more uprisings against the Kamakura bakufu increased across the country. Eventually, the main political center, Rokuhara Tandai (六波羅探題) of the Kamakura bakufu, fell. Nitta Yoshisada (新田義貞)*, who led another uprising group, attacked Kamakura and won. The Kamakura bakufu fell in 1333.

Emperor Go-Daigo initiated a new political system called Kenmu no Shinsei (建武の新政). However, his new system turned out to be a disaster. He made great efforts to set things right and drastically changed the old political system. Yet, this political reform created big unrest. It was not beneficial for anyone, and no one gained anything. Ashikaga Takauji (one of the key figures of merit) and his men did not receive any high-ranking positions. This reform was highly idealistic and too advanced for its time. It proved disadvantageous for the noblemen. His new policies only caused chaos and corruption.

Now, Ashikaga Takauji turned against Go-Daigo and defeated him. Go-Daigo left the Imperial Palace and established a new government in Yoshino, south of Kyoto. Therefore, it was called the Southern Dynasty. Meanwhile, Ashikaga Takauji set up a new emperor, Emperor Komyo (光明), in Kyoto and established the Northern Dynasty. This is how the Northern and Southern Dynasties arose.

Two dynasties co-existed for about 60 years. Gradually, many samurai groups moved to the Northern Dynasty, and after Go-Daigo and several of his key men died, the Southern Dynasty weakened. Eventually, the Southern Dynasty accepted an offer from the Ashikaga side, and the North and South united in 1392. Throughout these conflicts between the emperor and the Kamakura bakufu, sword styles became broader and longer, reaching 3, 4, or even 5 feet. Later, most Nanboku-cho (North and South Dynasties) style long swords were shortened.

Kibamusha (騎馬武者蔵) This portrait was once believed to depict Ashikaga Takauji, but now some claim otherwise. “Public Domain” owned by the Kyoto National Museum

*Nitta Yoshisada (新田義貞)

When Minamoto-no-Yoritomo established the Kamakura bakufu, he chose the Kamakura area as its center because it is surrounded by mountains on three sides and one side faces the ocean. This made it hard to be attacked and easier for them to defend themselves. They built seven narrow, steep roads through the mountains called Kir- toshi (切り通し), connecting with several major cities. These seven routes were the only roads in and out of Kamakura.

When Nitta Yoshisada attempted to attack Kamakura, he first attempted the land route but failed. He then approached the town from the ocean side, but the cliff stretched far out into the sea, making it impossible for them to pass. The legend says that when Nitta Yoshisada reached the area called Inamura Gasaki (稲村ヶ崎), he threw his golden sword into the ocean and prayed. Then the tide receded, allowing all the soldiers to walk around the cliff on foot. They charged into Kamakura, and the Kamakura bakufu fell. There are several different views on this story. Some scholars argue it is not true; some say it happened, but the date was wrong; others say that an unusual ebb tide occurred that day, and so on.

Today, Inamura Gasaki in the Shonan area (湘南) is one of the favorite evening dating spots for young people. The evening view at Inamura Gasaki is beautiful. The sunset over Inamura Gasaki towards Enoshima (江の島, a small island with a shrine on the hilltop) is stunning. My parents’ house used to sit above the cliff in an area called Kamakura-yama, overlooking the ocean.

Inamura Gasaki Photo is “Creative Commons” CC 表示-継承 3.0 File: Inamuragasaki tottanbu.jpg Public domain

The stone wall scene. Photo from Wikipedia. Public Domain

The stone wall scene. Photo from Wikipedia. Public Domain

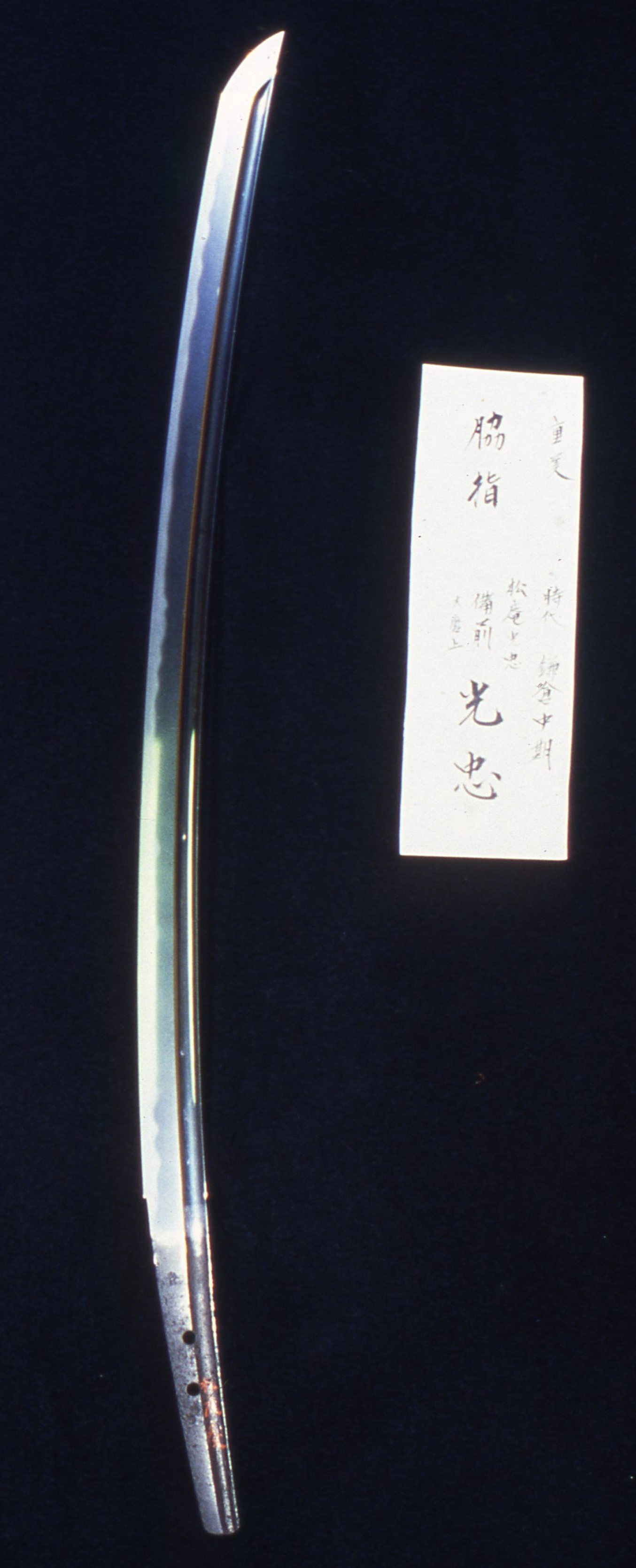

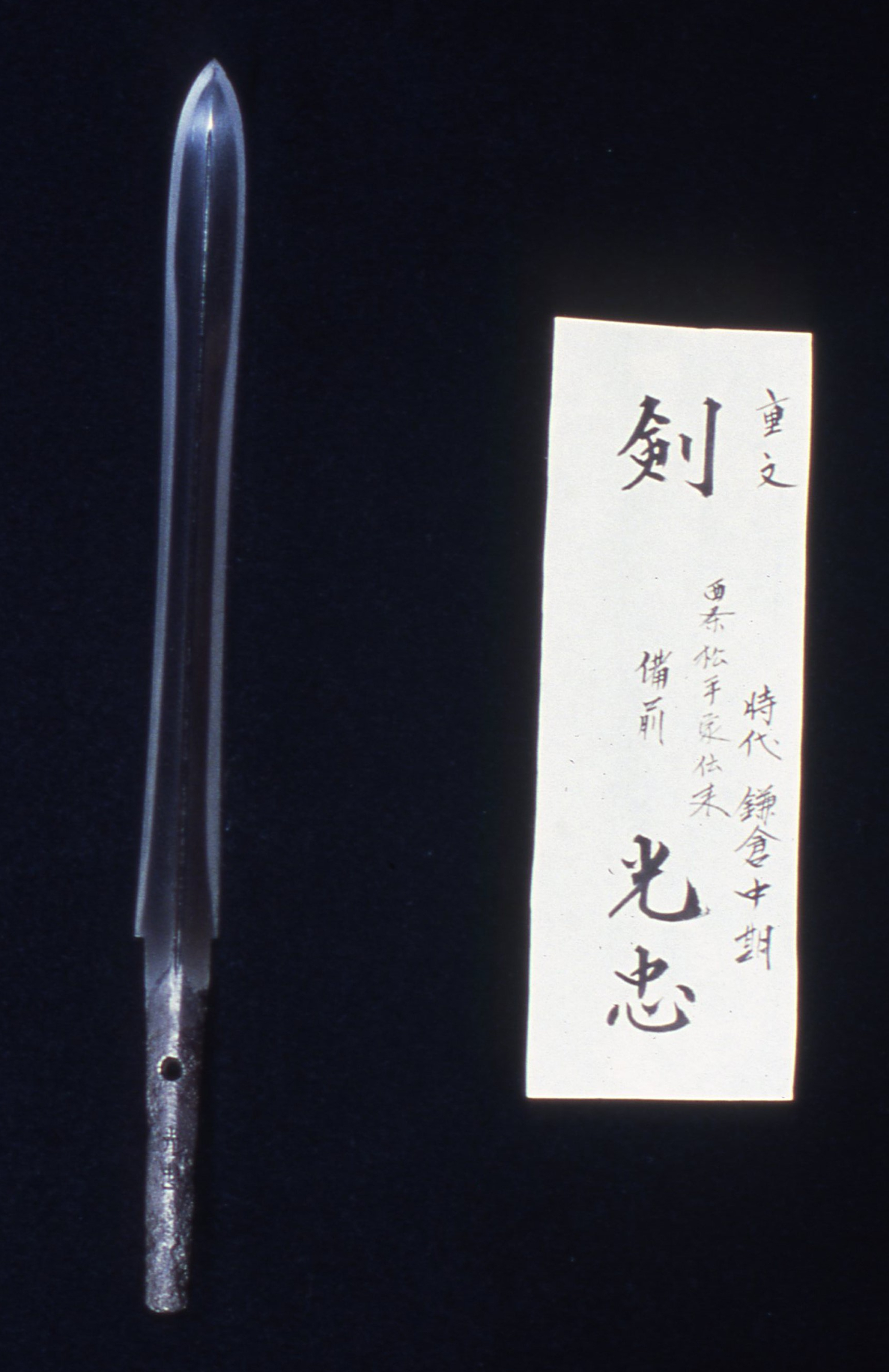

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bukazai) Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bunakzai)

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bukazai) Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Bunakzai)

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Token) Osafune Mitsutada(Juyo Bunkazai)

Osafune Mitsutada (Juyo Token) Osafune Mitsutada(Juyo Bunkazai)

The tomb of Minamoto-no-Yoritomo. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.

The tomb of Minamoto-no-Yoritomo. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.