This is a detailed section of Chapter 20, Muromachi Period History. Please read Chapter 20 before reading this part.

The red circleabove indicate the time we discuss in this chapter

Until the Muromachi (室町) period, the study of political history and sword history ran in parallel. The timelines above show that the middle line represents sword history, and the bottom line represents political history.

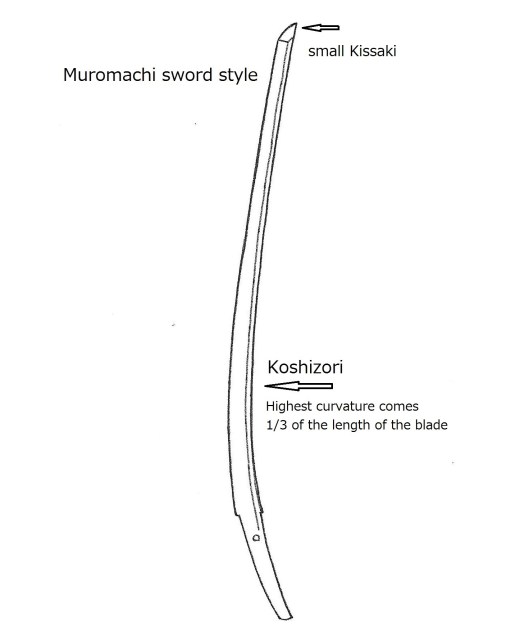

The styles of swords were distinctly different between the Muromachi and Sengoku periods (戦国時代). Therefore, for sword study, the Muromachi and Sengoku periods should be separated. Japanese history textbooks define the Muromachi period as 1393 (the end of the Nanboku-cho) to 1573, when Oda Nobunaga (織田信長) deposed Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki (足利義昭) from Kyoto (the fall of the Muromachi bakufu). In these textbooks, the Sengoku period is considered part of the Muromachi period. However, we need to distinguish between the Muromachi and Sengoku periods for the study of swords.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (足利義満)

The best period during the Muromachi era was when Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (足利義満: grandson of Ashikaga Takauji) was in power. He moved the bakufu to Muromachi (室町) in Kyoto; therefore, this era is called the Muromachi period. By the time most of the South Dynasty’s samurai had surrendered to the North Dynasty, the South Dynasty had accepted Shogun Yoshimitsu’s offer to stop fighting against the North. This acceptance established the Ashikaga family’s power within the Muromachi Bakufu.

Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu generated tremendous profits from trade with China (Ming). He built a famous resort villa in Kyoto, the Golden Pavilion (Kinkaku-ji Temple 金閣寺*). It is believed that he created the Golden Pavilion to display his power and wealth. The beautiful culture known as Kitayama Bunka (Kitayama culture 北山文化) flourished during this period.

*Golden Pavilion (金閣寺: Kinkaku-ji Temple) —– Its official name is Rokuon-ji Temple (鹿苑寺). Saionji Kintsune (西園寺公経) originally built it as his resort house during the Kamakura period. Shogun Yoshimitsu acquired it in 1397 and turned it into his villa. He also used it as an official guesthouse.

After Shogun Yoshimitsu’s death, the villa was converted into Rokuon-ji Temple. It is part of the Rinzaishu Sokoku-ji Temple, which served as the main temple of a Zen sect denomination, called the Rinzaishu Sokoku-ji group (臨済宗相国寺派). Kinkaku-ji is a reliquary hall that contains relics of the Buddha. Kinkaku-ji Temple represents the grand Kitayama Bunka (Kitayama culture). In 1994, it was designated a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site. https://www.shokoku-ji.jp/kinkakuji/

My photo May 2019,

My photo May 2019,

Ashikaga Yoshimasa (足利義政)

After the death of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (足利義満), the Muromachi bakufu became less financially stable, and its military power declined. Consequently, the daimyo (feudal lords) increased their control. A few generations after Shogun Yoshimitsu, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, the eighth Shogun, took power. His wife was the well-known Hino Tomiko (see Hino Tomiko in Chapter 20, Muromachi Period History).

It is said that Shogun Yoshimasa was not interested in his role as shogun; instead, he was more interested in art and culture. He laid the foundation for today’s Japanese art and culture, including the Japanese garden, Shoin-zukuri (書院造) interior design, the tea ceremony, flower arrangements, painting, and other art forms. His cultural influence is known as Higashiyama Bunka (Higashiyama culture (東山文化).

As described in Chapter 20, Muromachi Period History (室町時代), Shogun Yoshimasa did not have any children. His brother Yoshimi (義視) was expected to become the next Shogun. However, his wife, Hino Tomiko, gave birth to a son, Yoshihisa (義尚). Hino Tomiko sought support from Yamana Sozen (山名宗全: a powerful family) to back her son. Meanwhile, the brother, Yoshimi, was connected with Hosokawa Katsumoto (細川勝元: another powerful family). The problem was that Shogun Yoshimasa paid too much attention to his cultural pursuits and failed to address the issue he created by not being clear about who should succeed him as Shogun. He did not hand over the shogunate to either party.

In 1467, in addition to the succession problem and conflicts of interest among powerful daimyo, a civil war, known as “Onin-no-run (応仁の乱),” broke out. All daimyo were divided, siding with either the Hosokawa or the Yamana factions. Eventually, the war spread throughout Japan and lasted more than 10 years. Finally, in 1477, after the deaths of Hosokawa Katsumoto and Yamana Sozen, Shogun Yoshimasa decided to transfer the shogunate to his son Yoshihisa. As a result of this war, Kyoto was devastated, and the power of the Muromachi Bakufu declined significantly.

While all this was happening and people were suffering, Yoshimasa continued to spend money on building the Ginkaku-ji Temple (銀閣寺: The Silver Pavilion). He died before seeing the completion of Ginkaku-ji Temple. The Onin-no-ran would lead to the next Sengoku period, a 100-year-long Warring States period.

*Shoin-zukuri (書院造)———- A traditional Japanese residential interior style with Tatami mats, a nook, and shoji screens (sliding doors). This style forms the basis for interior design in modern Japanese homes.

Shoin Zukuri style Japanese room

Public Domain GFDL,cc-by-sa-2.5,2.0,1.0 file: Takagike CC BY-SA 3.0view terms File: Takagike Kashihara JPN 001.jpg

My Japanese room

My Japanese room