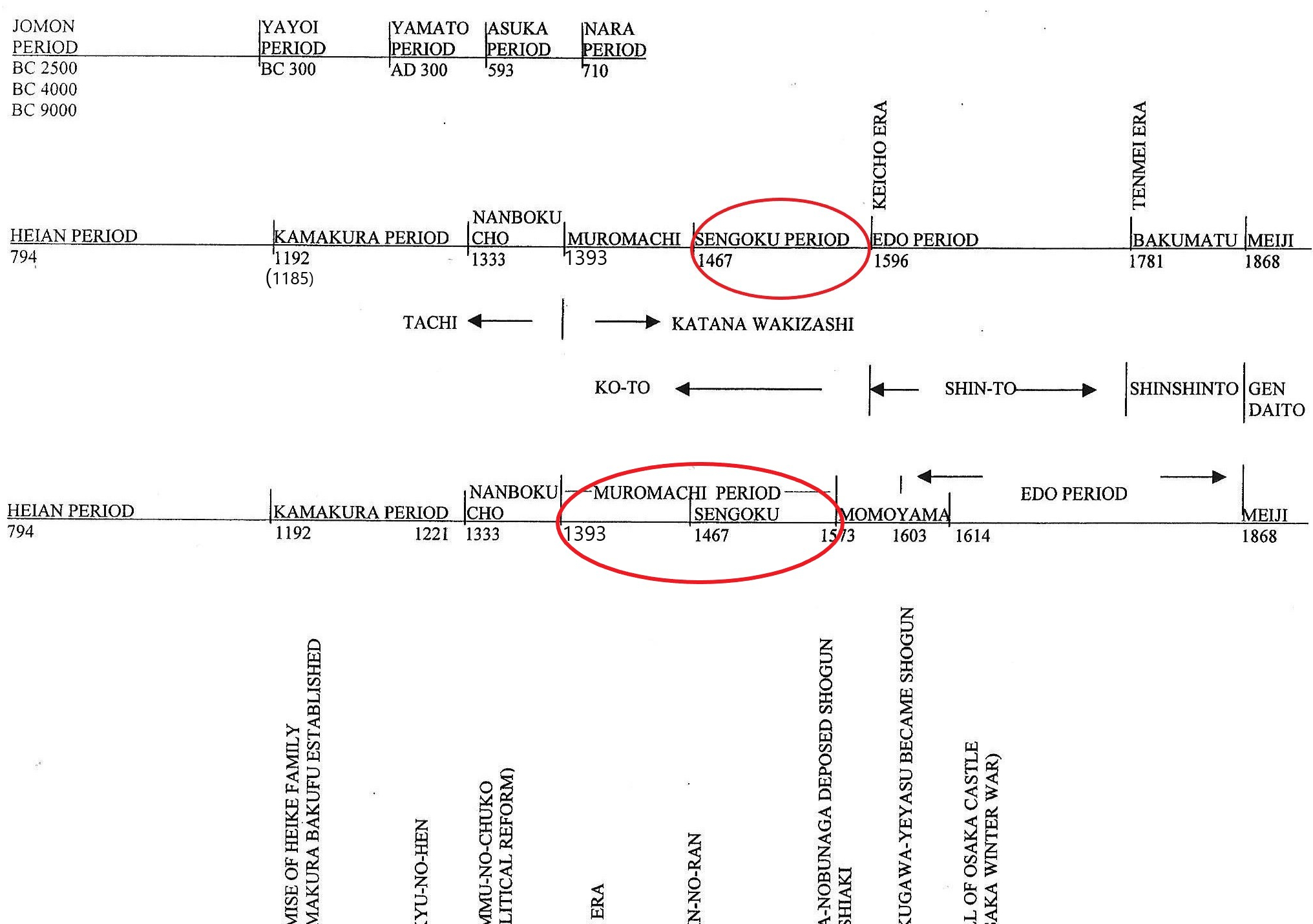

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The timeline above shows two circles. In political history, the Sengoku period (戦国時代) is part of the Muromachi period (室町), which is the lower circle. However, in sword history, we separate the Muromachi and Sengoku periods (Warring States period), the top circle. In sword history, we divide the time this way because, during those two periods, sword styles changed, and the environment of sword-making also changed.

After the Onin-no-ran (応仁の乱) began (discussed in 20|Muromachi Period History), the beautiful capital city of Kyoto (京都) was in a devastated condition. The shogun’s (将軍) power reached only over a small area. The rest of the country was divided into about thirty small independent states. The leaders of these independent states were called shugo daimyo (守護大名). They were originally government officials who were appointed and sent there by the central government.

Powerful local samurai often became the leaders of these states. They fought against each other to take over each other’s land. During the Sengoku period, vassals would kill their lords and steal their domains, or farmers would revolt against their lords. A state like this is called “gekoku-jo” (lower-class samurai overthrow the superior).

This was the time of the Warring States, known as the Sengoku period. The leader of each state was called a Sengoku daimyo (戦国大名: Warlord). The Sengoku period lasted about 100 years. Gradually, powerful states defeated weaker ones through long, fierce battles, expanding their territory. Around thirty small countries became twenty, then ten, and so on. Eventually, only a few dominant sengoku daimyo (warlords) remained. Each daimyo from those states fought their way to Kyoto and tried to become the top ruler of Japan. The first one who almost succeeded was Oda Nobunaga (織田信長). However, he was killed by his vassal, Akechi Mitsuhide (明智光秀), and soon Akechi was killed by his colleague, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉).

After Toyotomi Hideyoshi defeated Akechi Mitsuhide, his troops, and other major warlords, he nearly completed the unification of Japan. Yet, Hideyoshi still had one more rival to deal with to finish his goal. That was Tokugawa Iyeyasu (徳川家康). Now, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu are the last contenders for the top position. Both recognized that their opponents were smart and capable. Any wrong move could be disastrous. Therefore, they decided to maintain a friendly coexistence on the surface for the time being. Although Toyotomi Hideyoshi tried to make Tokugawa Ieyasu his vassal, Tokugawa Ieyasu somehow managed to avoid that. In Tokugawa Ieyasu’s mind, being younger than Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he knew he could simply wait until Hideyoshi‘s natural death, which eventually happened.

After Hideyoshi’s death, Tokugawa Ieyasu fought Hideyoshi’s vassals and won at the Battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原の戦い) in 1600. Then, in 1615, at the Battle of the Osaka Natsu-no-jin (Osaka Summer Campaign: 大阪夏の陣), Tokugawa defeated Hideyoshi’s son’s army. Following this, the Toyotomi clan was dissolved entirely, and the Edo (江戸) period began. It is called the Edo period because Tokugawa Ieyasu lived in Edo, which is now Tokyo (東京).

*The Sengoku period is frequently depicted in TV dramas and movies. People who lived through that era had a tough time, but it was also the most exciting time for creating TV shows and films. The lives of Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu are among the most popular stories in Japan. In particular, the story of Toyotomi Hideyoshi is among the most popular. His background was that of a poor farmer, but he rose to become the top ruler of Japan. That is a fascinating success story.

Portrait of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉) by Kano Mitsunobu, owned by Kodai-Ji Temple From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repositon.