Chapter 59 is a detailed section of Chapter 25 Edo Period History (江戸時代歴史). Please read Chapter 25 before reading this part.

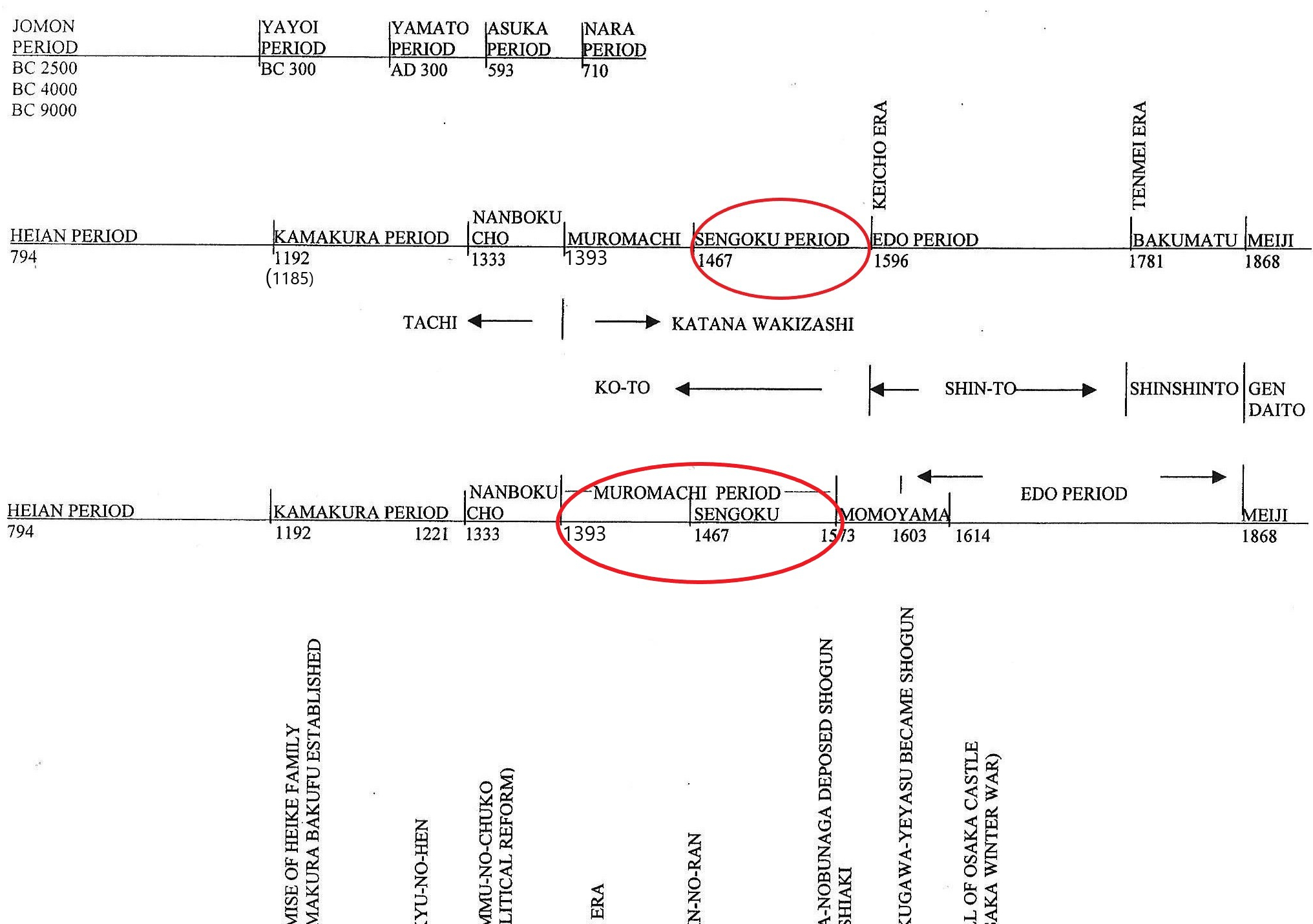

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

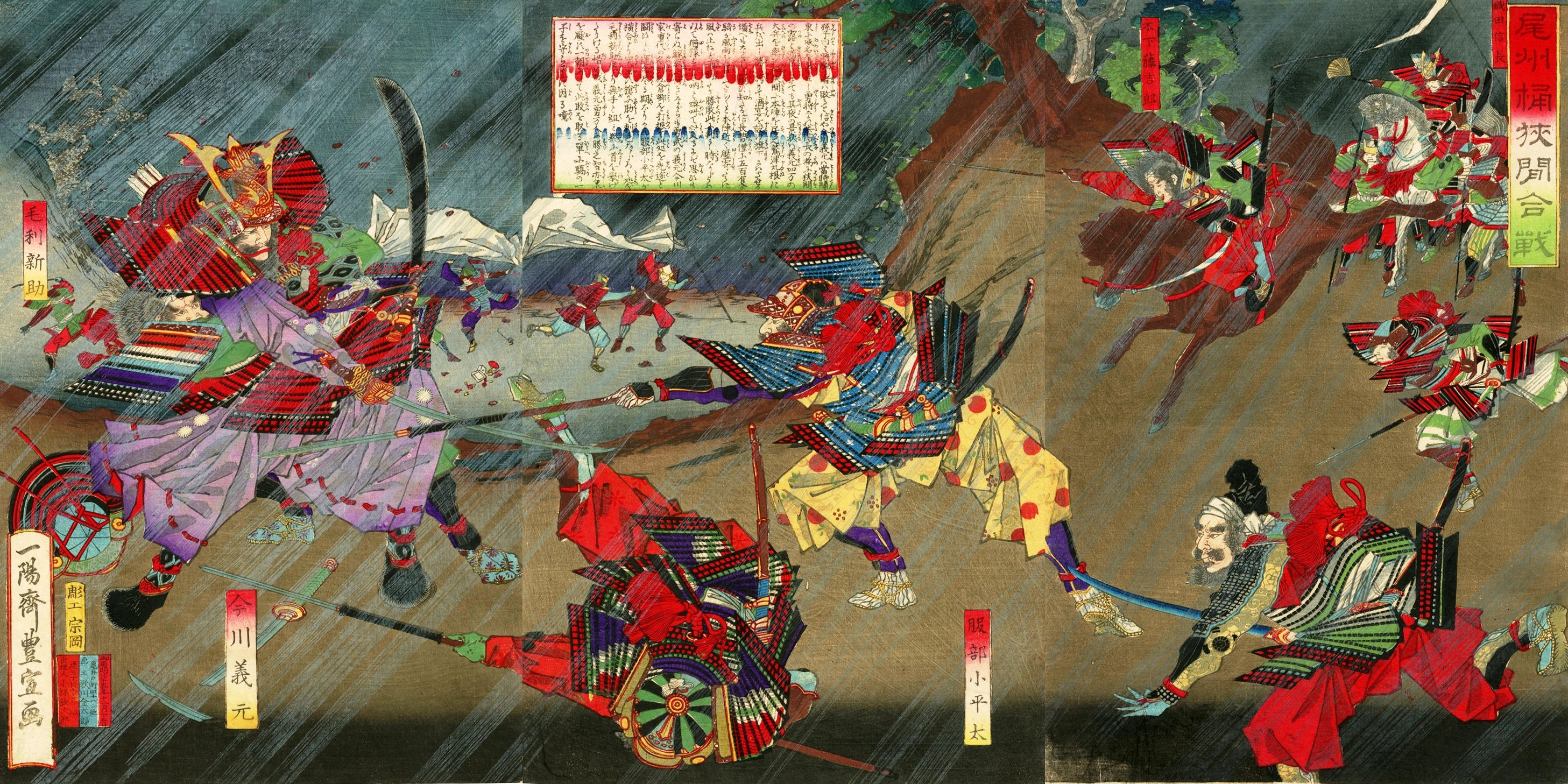

Battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原合戦)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉), the most powerful figure during the Sengoku and Momoyama periods, died in 1598. His heir, Hideyori (秀頼), was only five years old. Before his death, Hideyoshi established a council system composed of the top five daimyo to oversee Hideyori’s affairs as regents until he reached adulthood.

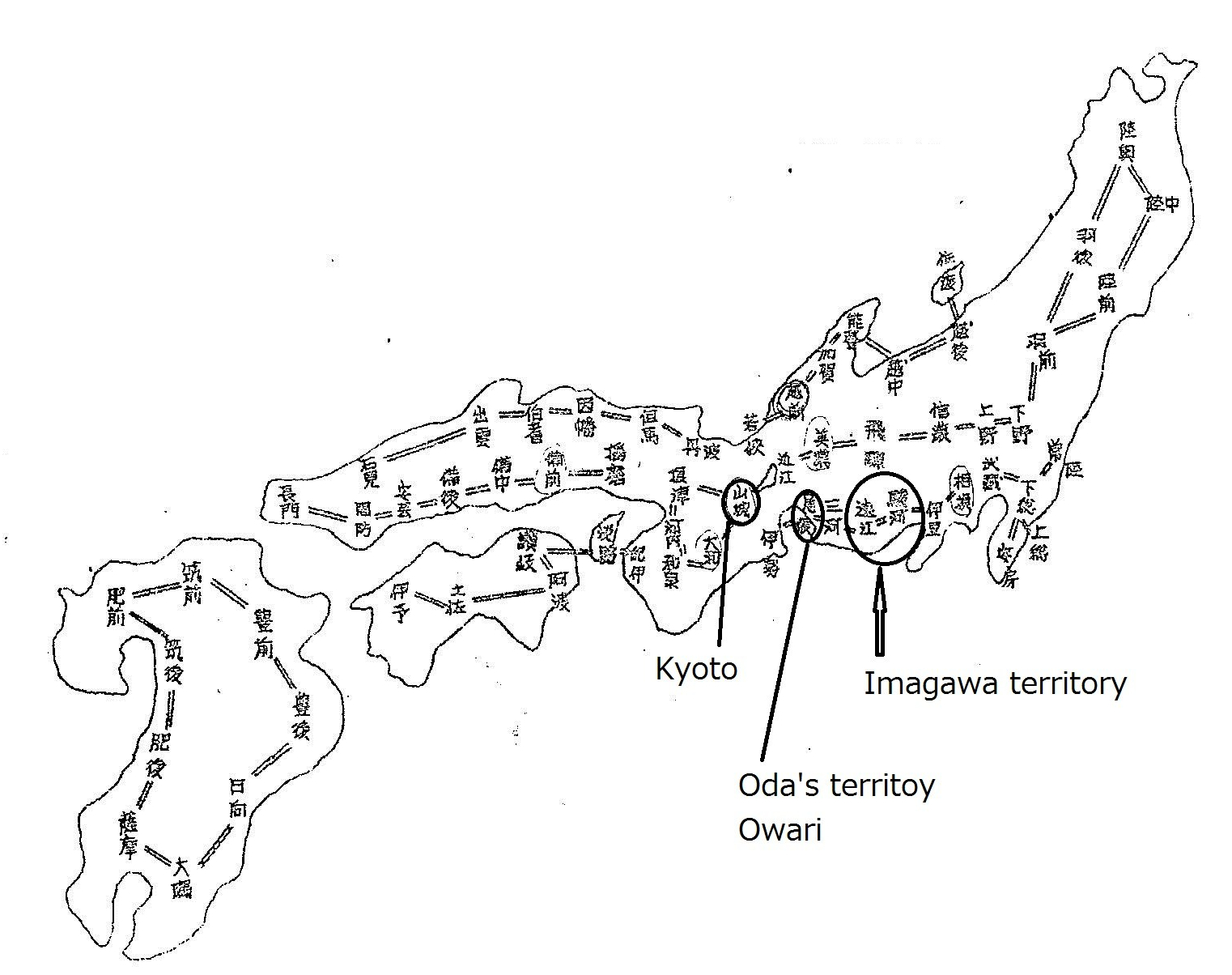

At Hideyoshi’s deathbed, all five Daimyo agreed to serve as guardians of Hideyori. However, over time, Ishida Mitsunari (石田三成) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康) began to disagree. In 1600, finally, the two main Daimyo clashed, leading to the Battle of Sekigahara. One side is called Seigun (the Western army), led by Ishida Mitsunari and the other is Togun (the Eastern army), led by Tokugawa Ieyasu. All the daimyo across the country sided either with Tokugawa or with Ishida Mitsunari. It is said that Mitsunari’s forces had 100,000 men, while Tokugawa’s forces had 70,000. Ieyasu had fewer soldiers, but he ultimately won. Ieyasu became the chief retainer of the Toyotomi clan, meaning he was virtually the top figure since Hideyori was still a child.

In 1603, Ieyasu became a Shogun. Now, Ieyasu took control of Japan, establishing the Tokugawa Bakufu (government) in Edo and eliminating the council system.

Toyotomi Hideyori lived with his mother, Yodo-gimi (or Yodo-dono), at Osaka Castle, which Hideyoshi had built before his death. Over time, tensions arose between Hideyori and Yodo-gimi in Osaka and Ieyasu in Edo. Yodo-gimi was a proud and headstrong person, and she had good reasons for it. She was the niece of Oda Nobunaga, the wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and the mother of Hideyori, the head of the Toyotomi clan. Later, her pride led her into trouble and contributed to the Toyotomi clan’s downfall.

Siege of Osaka: Winter (1614) and Summer ( 1615) Campaigns

During the 15 years between the Battle of Sekigahara and the Siege of Osaka Castle, tensions between the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Toyotomi clan steadily increased. Before the Battle of Sekigahara, the Toyotomi clan ruled Japan. After Sekigahara, the Tokugawa bakufu took control of Japan. The Toyotomi clan lost many key advisors and vassals in the battle. As a result, Toyotomi’s power remained centered on Yodo-gimi. By the time of the siege, Hideyori had grown into a fine young man, but Yodo-gimi had overly protected and controlled her son. She wouldn’t even let Hideyori practice kendo (the traditional Japanese swordsmanship), claiming it was too dangerous.

She persistently acted as if the Toyotomi clan still held the highest power. Tokugawa Ieyasu tried to ease tensions by arranging for his granddaughter, Sen-hime, to marry Hideyori. A few advisors suggested that Yodo-gimi should yield to Tokugawa, but she insisted that Tokugawa must subordinate himself to Toyotomi. Rumors began circulating that the Toyotomi side was recruiting and gathering many ronin (unemployed samurai) within Osaka Castle. Several key figures tried to mediate between the Toyotomi and Tokugawa clans but were unsuccessful.

Finally, Ieyasu led his army to Osaka, and in November 1614, he launched a campaign to siege Osaka Castle (the Winter Campaign). It is said that the Toyotomi side had 100,000 soldiers, though some were merely mercenaries. However, Osaka Castle was built almost like a fortress, making it very difficult to attack. The Tokugawa army attacked fiercely and fired cannons daily, but they realized the castle was so well built that it was a waste of time to keep trying.

Eventually, both sides entered peace negotiations. They agreed on several items in the treaty. One of them was to fill the outer moat of Osaka Castle. However, the Tokugawa side filled both the outer and inner moats. That angered the Toyotomi side, and they became suspicious that the Tokugawa might not keep the agreement.

Another agreement was the disarmament of the Toyotomi clan. However, the Toyotomi side kept their soldiers inside the castle. Tokugawa issued a final ultimatum to the Toyotomi side: remove all soldiers from the castle or vacate it. Yodo-gimi refused both demands.

After that, another siege started in the summer of 1615 (the Summer Campaign). It is said that the Toyotomi had 70,000 men, whereas the Tokugawa had 150,000. Both sides fought in several battles here and there, but the early battles did not go well for either side due to thick fog, delayed troop arrivals, and miscommunication. The final battle took place at Osaka Castle. The Toyotomi decided to stay inside the castle, but soon, a fire broke out from within and burned the castle down. Yodo-gimi and Hideyori hid inside a storage building, waiting for Ieyasu’s response to their pleas for mercy. They hoped their daughter-in-law could negotiate the terms of the deal. However, it was not accepted, and both died inside the storage building.

Nene and Yodo-gimi

Nene was the lawful wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. She was a bright and wise person, despite not being of noble birth. Everyone respected her, including Tokugawa Ieyasu. Even Hideyoshi often valued her opinions on political matters. She helped Hideyoshi rise through the ranks. However, Nene was unable to have children. Toyotomi Hideyoshi sought out other women everywhere, hoping to produce an heir, but none could have his child except Yodo-gimi. Naturally, rumors circulated about who the real biological father was. Speculation pointed to several men, one of whom was Ishida Mitsunari.

伝 淀殿画像(possibly of Yodo-dono, but not confirmed)Owned by the Nara Museum of Art, Public Domain: Yodo-dono cropped.jpg from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.

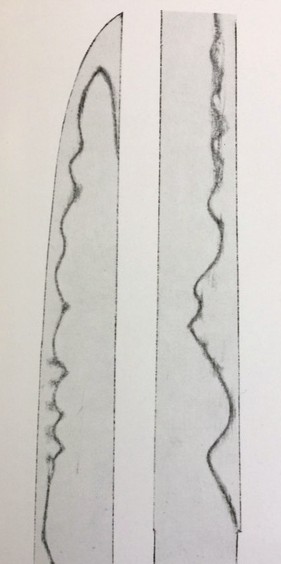

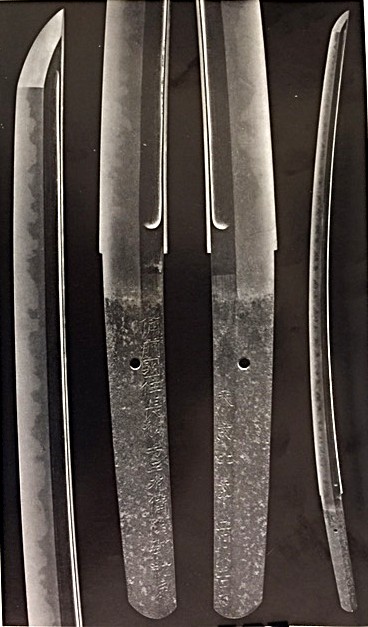

Bizen Osafune Yosozaemon Sukesada (備前国住長船与三左衛門尉祐定) from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted).

Bizen Osafune Yosozaemon Sukesada (備前国住長船与三左衛門尉祐定) from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted).

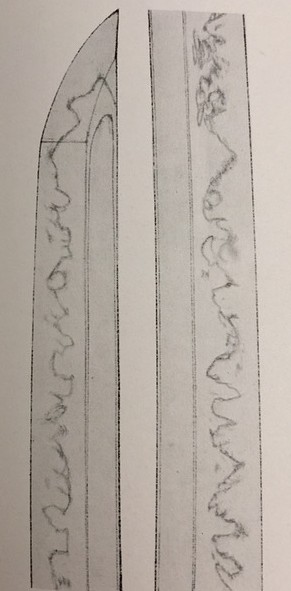

Izuminokami Fujiwara Kanesada (和泉守藤原兼㝎) from Sano Museum Catalog

Izuminokami Fujiwara Kanesada (和泉守藤原兼㝎) from Sano Museum Catalog

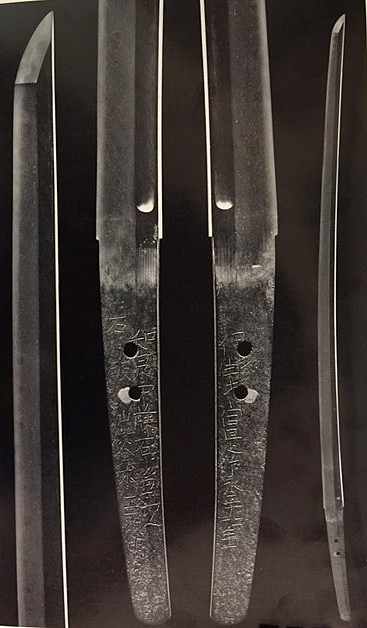

Bizen Osafune Norimitsu (備前長船法光) from Sano Museum Catalog, permission granted.

Bizen Osafune Norimitsu (備前長船法光) from Sano Museum Catalog, permission granted.

My photo May 2019,

My photo May 2019,

My Japanese room

My Japanese room