Chapter 55 is a detailed section of Chapter 21, Muromachi Period Sword. Please read Chapter 21 before reading this part.

The circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

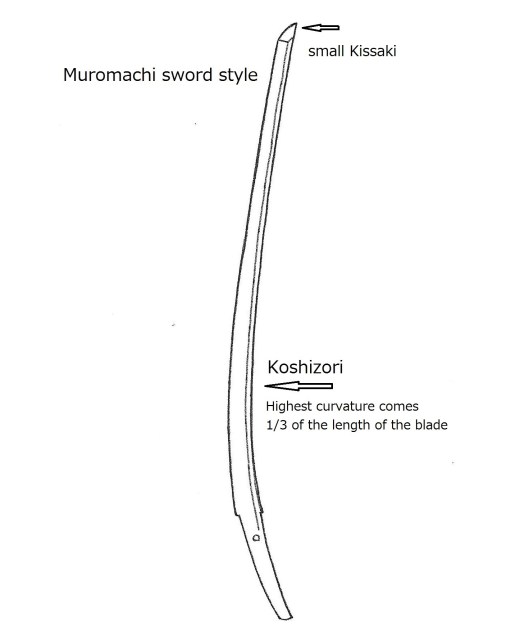

After the Muromachi period, swords shifted to katana(刀) from tachi (太刀), as described in Chapter 21, Muromachi Period Sword. Refer to Chapter 21, Muromachi Period Sword. By the end of the Nanboku-cho period, sword lengths had shortened to about 2 feet ± a few inches. The 3-to-5-foot-long swords seen during the Nanboku-cho period were no longer produced. This change occurred because, during the Nanboku-cho period, warriors mainly fought on horseback, but after the Muromachi period, infantry combat became more common.

Oei Bizen (応永備前) The pronunciation of Oei is “O” as in “Oh” and “ei” as in “A” from ABC. The Muromachi period was a declining time for sword-making. The swords made during the early Muromachi period in the Bizen area is known as Oei Bizen. Osafune Morimitsu (長船盛光), Osafune Yasumitsu (長船康光), and Osafune Moromitsu (長船師光) were the main Oei Bizen swordsmiths. Soshu Hiromasa (相州広正) and Yamashiro Nobukuni (山城信國) were also similar to the Oei Bizen style. Please refer to Chapter 21, Muromachi Period Sword, for details on the Muromachi sword shape, Hamon, Boshi, and Ji-hada.

Bishu Osafune Moromitsu (備州長船師光) from Sano Museum Catalogue ((permission granted)

Bishu Osafune Moromitsu (備州長船師光) from Sano Museum Catalogue ((permission granted)

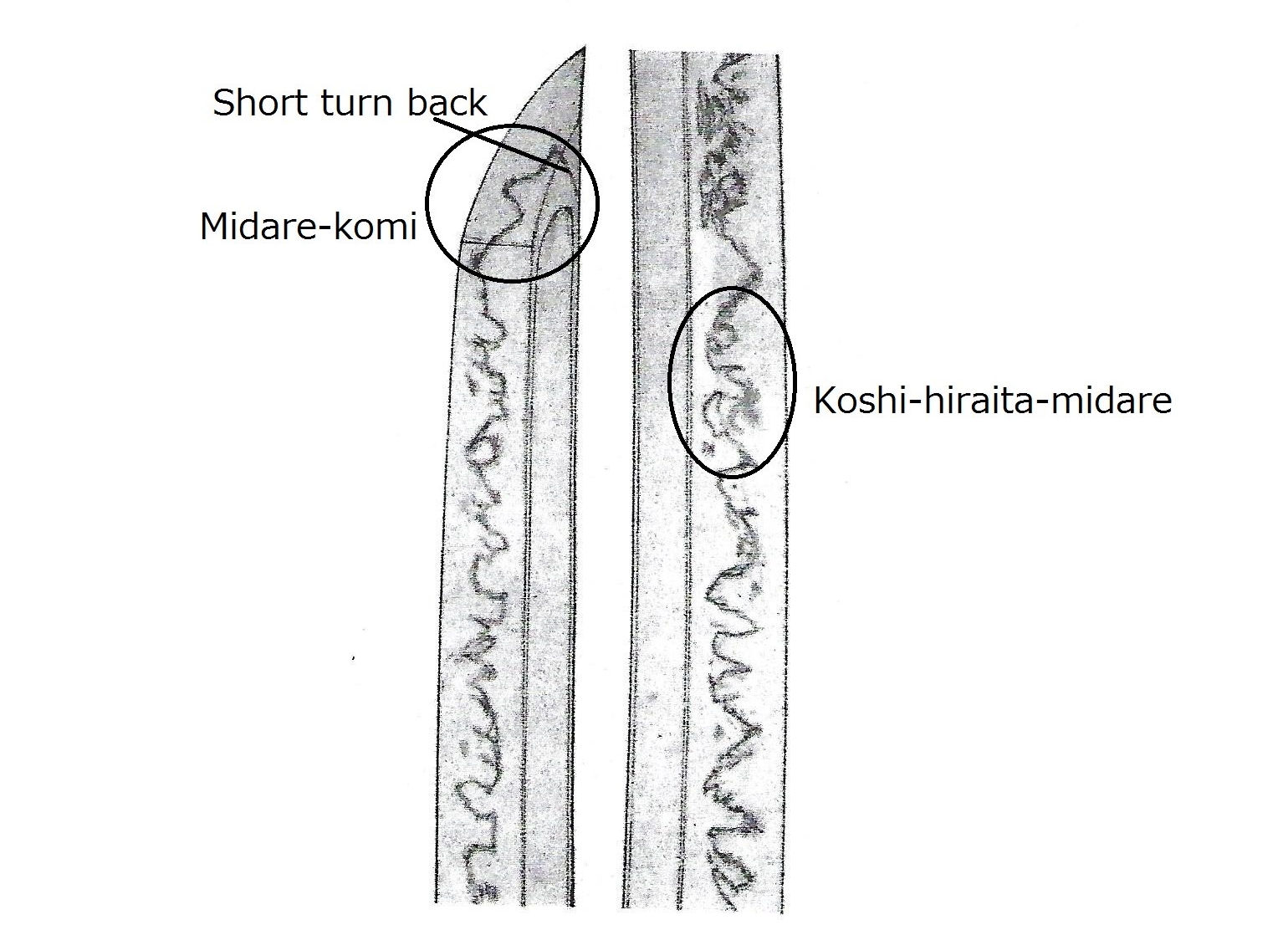

The Osafune Moromitsu sword shown above measures 2 feet 5 inches in length and has a medium kissaki. Its hamon has a small wave-like pattern with continuous gunome (a lined half-circle pattern). The boshi area shows irregular waviness with a slightly pointed tip. Very faint bo-utsuri (a soft shadow shaped like a strip of wood) appears on ji-hada. Bo-utsuri is a distinctive feature among all the Oei Bizen.

Before the Muromachi period, many swordsmith groups operated in the Bizen region. However, by the Muromachi period, Osafune (長船) was the only remaining group.

Osafune (長船) is the name of a region, but it became the surname of swordsmiths during the Muromachi period. Two other well-known swordsmiths from Oei Bizen are Osafune Morimitsu (盛光) and Osafune Yasumitsu (康光). The hamon created by Morimitsu and Yasumitsu is more detailed than that of the sword in the photo above. Chapter 21, Muromachi period swords, shows the hamon of Morimitsu and Yasumitsu and describes the typical characteristics of swords from the Muromachi period.

Hirazukuri Ko-Wakizashi Tanto

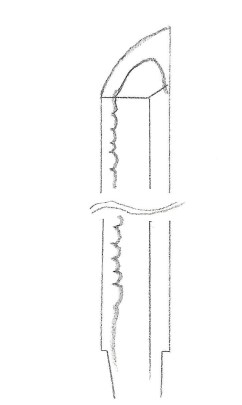

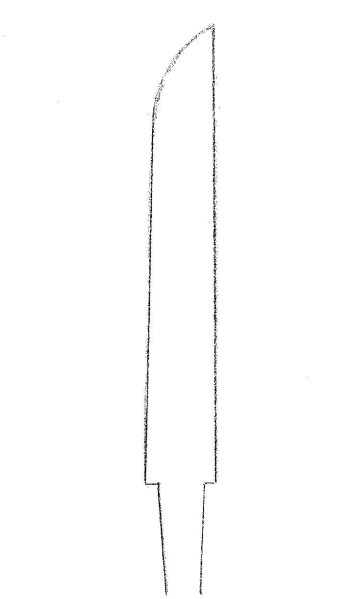

Hirazukuri Ko-Wakizashi Tanto Shape

Hirazukuri ko-wakizashi tanto was a popular style during the early Muromachi period. Swordsmiths from various regions produced tantos similar to the one shown above. However, most of these types were made by Oei Bizen swordsmiths.

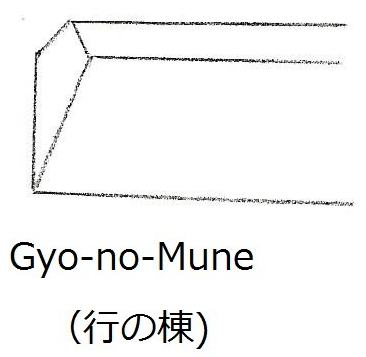

The characteristics of the Hirazukuri ko-wakizashi tanto ————-Typically about one foot and 1 or 2 inches long. No yokote line, no shinogi, and no sori (meaning no curvature, straight back). Average thickness. Narrow width. Gyo-no-mune (refer to Chapter 12, Middle Kamakura Period Tanto).

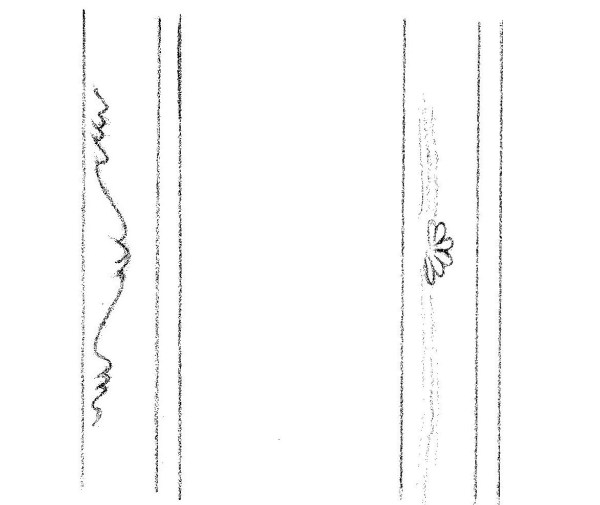

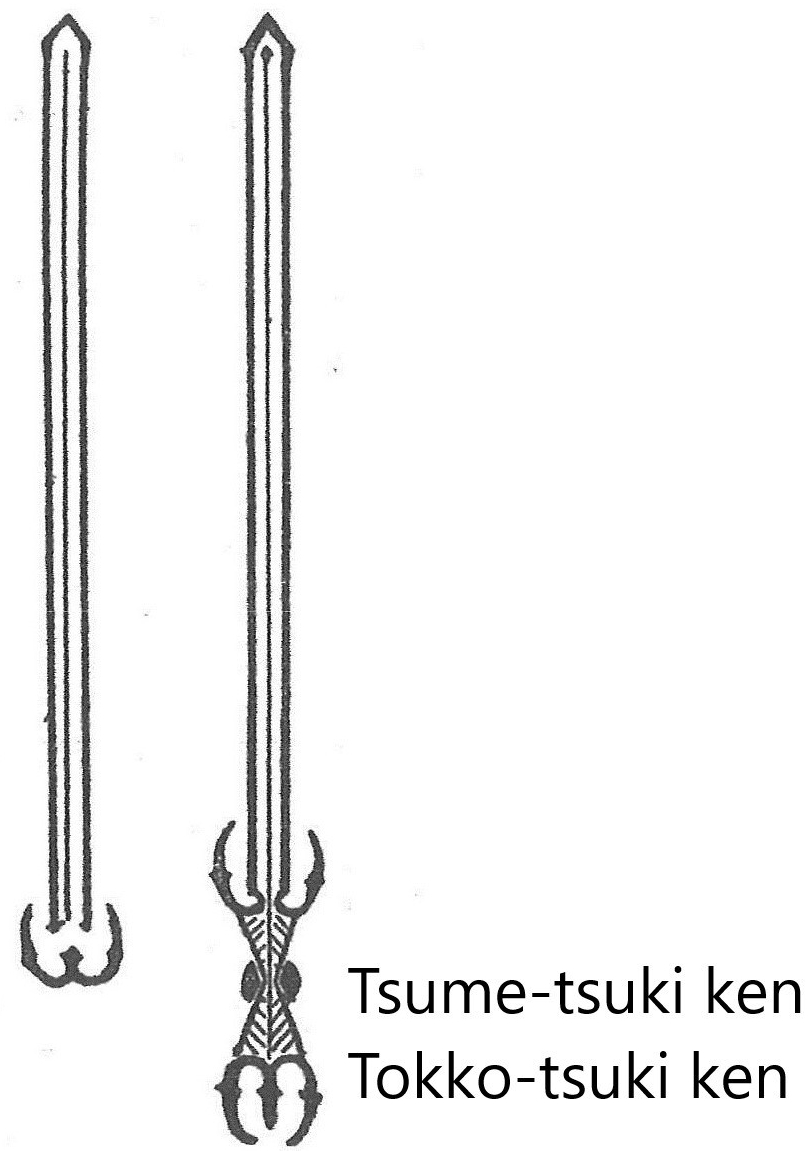

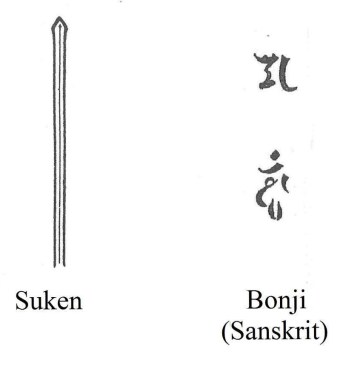

Hirazukuri Ko-wakizashi tanto often shows many engravings. Hi with soe-hi (double lines, wide and narrow side by side), Tokko-tsuki-ken, Tsume-tsuki-ken, Bonji, and more.

.

*drawings from “Nihonto no Okite to Tokucho” by Honami Koson