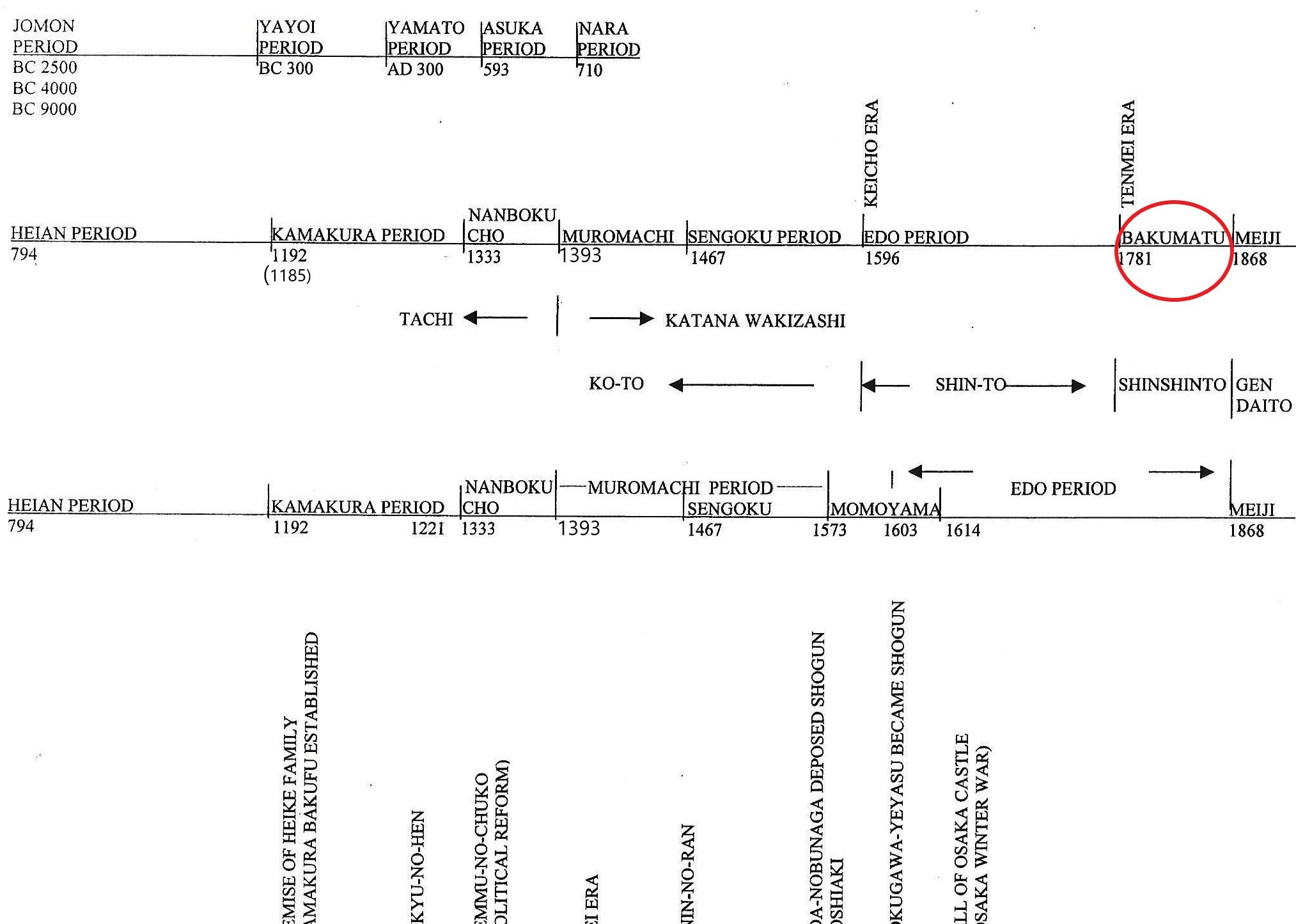

This Chapter is a detailed Chapter of the 30|Bakumatsu Period, Shin Shin-to. Please read Chapter 30 before reading this chapter.

The circle Above indicates the time we discuss in this chapter.

Swords made between the Tennmei era (天明 1781) and the end of the Keio era (慶應) are called shin shin-to. Please refer to the timeline above. This period was when Japan was moving toward the Meiji Restoration, known as the Bakumatsu era. During this time, sword-making became active again. Below are the well-known swordsmiths from the main areas.

Musashi no Kuni (武蔵の国: Tokyo today)

Suishinshi Masahide (水心子正秀) ——— When Suishinshi Masahide made Yamashiro-den style swords, their shapes resembled those of ko-to period swords; funbari, an elegant shape; chu-suguha (medium straight); komaru-boshi, with fine wood grain. When he forged in the Bizen style, he made a Koshi-zori shape, similar to a ko-to made by Bizen Osafune. Nioi with ko-choji, and katai-ha (refer to 30| Bakumatsu Period Sword 新々刀). In my old sword textbook, I noted that I saw Suishinshi in November 1970 and October 1971.

Taikei Naotane (大慶直胤) ————————–Although Taikei Naotane was part of the Suishinshi group, he was one of the top swordsmiths. He had an exceptional ability to forge a wide range of sword styles beautifully. When he made a Bizen-den style, it resembled Nagamitsu from the Ko-to era, with nioi. Also, he did sakasa-choji as Katayama Ichimonji had done. Katai-ha appears. The notes in my old textbook indicate I saw Naotane in August 1971.

Minamoto no Kiyomaro (源清麿) ————————– Kiyomaro wanted to join the Meiji Restoration movement as a samurai; however, his guardian recognized Kiyomaro’s talent as a master swordsmith and helped him become one. It is said that because Kiyomaro had a drinking problem, he was not very eager to make swords. At age 42, he committed seppuku. Kiyomaro, who lived in Yotsuya (now part of Shinjuku, Tokyo), was called Yotsuya Masamune because he was as good as Masamune. His swords featured wide-width, shallow sori, stretched kissaki, and fukura-kereru. The boshi is komaru-boshi. Fine wood grain ji-gane.

Settsu no Kuni ( 摂津の国: Osaka today)

Gassan Sadakazu (月山貞一) ———- Gassan excelled in the Soshu-den and Bizen-den styles, but he was capable of making in any style. He was as much a genius as Taikei Naotane. You must pay close attention to notice a sword made by Gassan from genuine ko-to. He also had remarkable carving skills. His hirazukuri-kowakizashi, forged in the Soshu-den style, looks just like a Masamune or a Yukimitsu. He forged in the Yamashiro-den style, with Takenoko-zori, hoso-suguha, or chu-suguha in nie. Additionally, he forged the Yamato-den style with masame-hada.

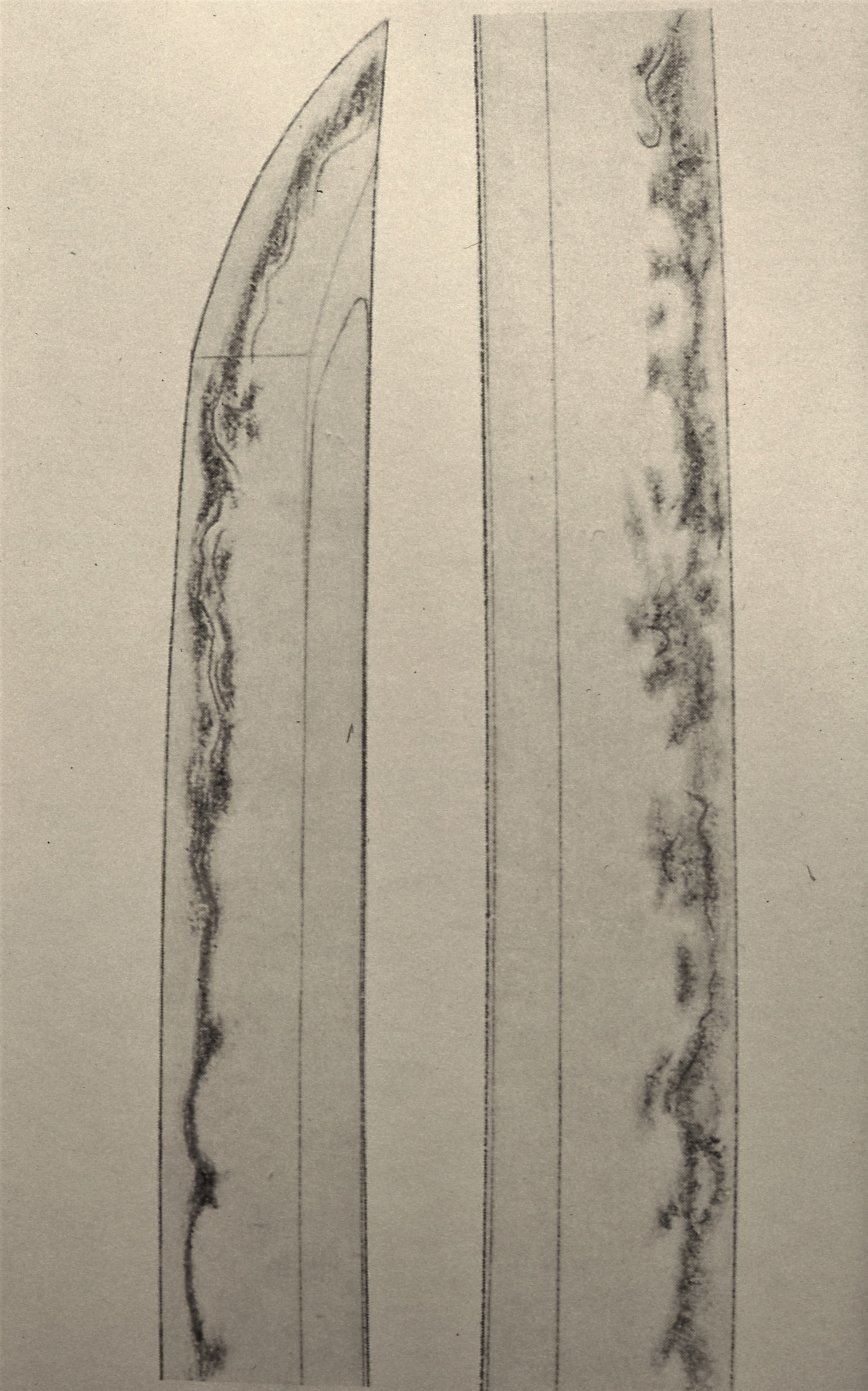

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

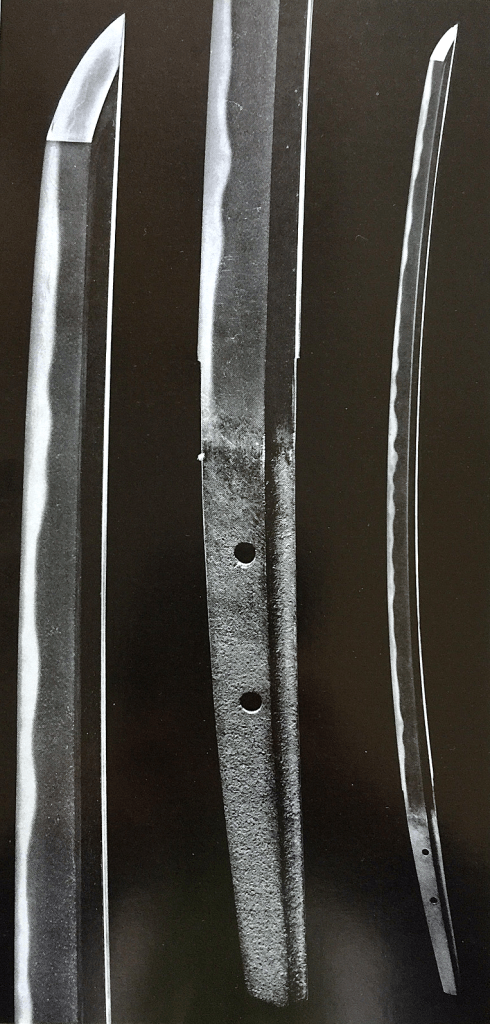

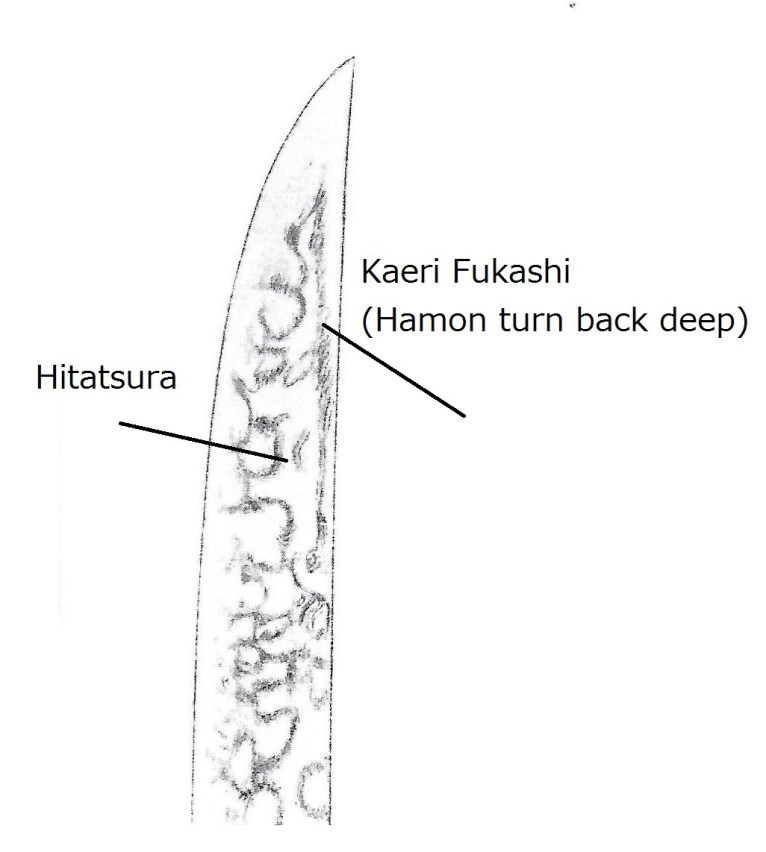

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)