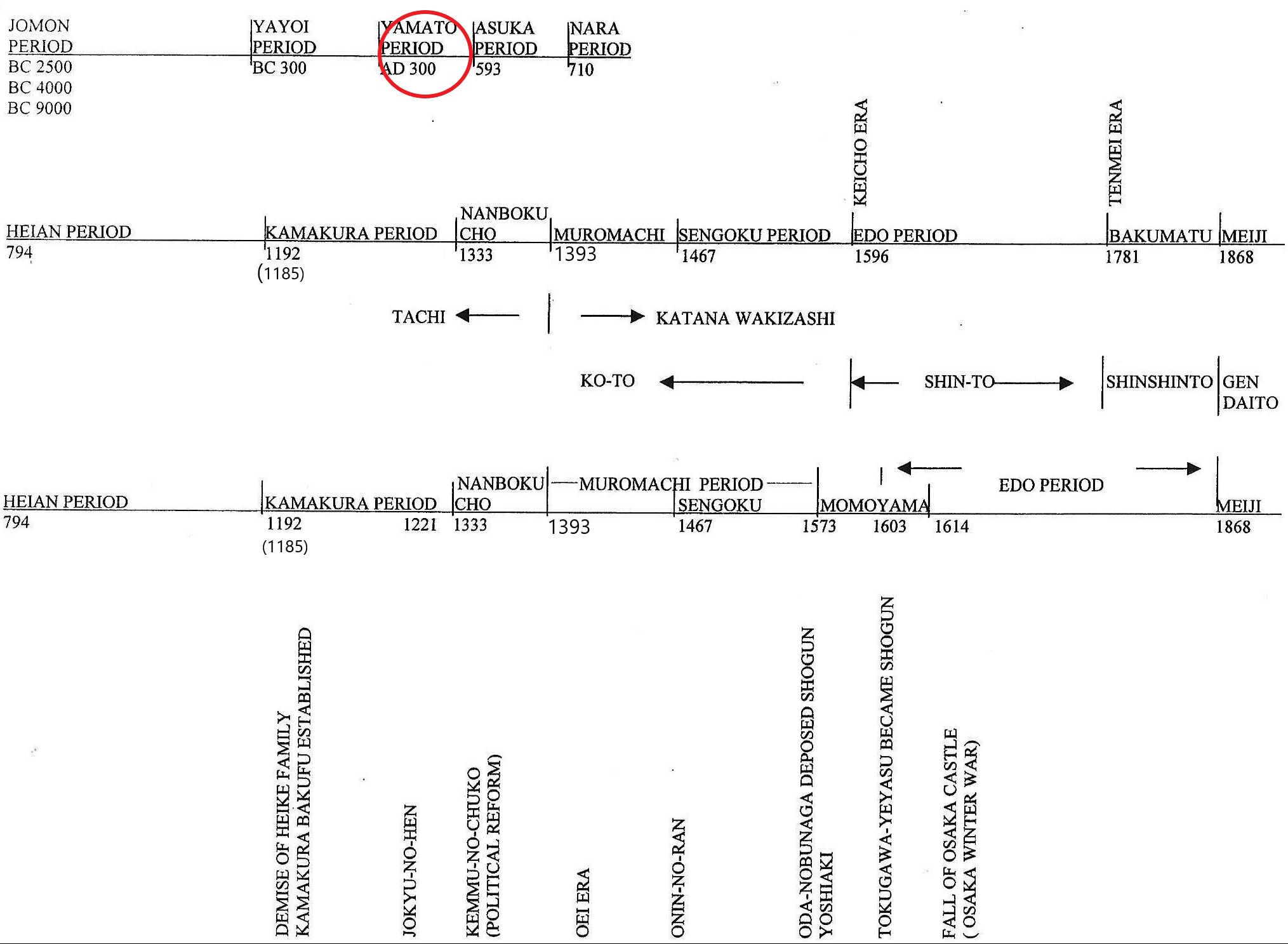

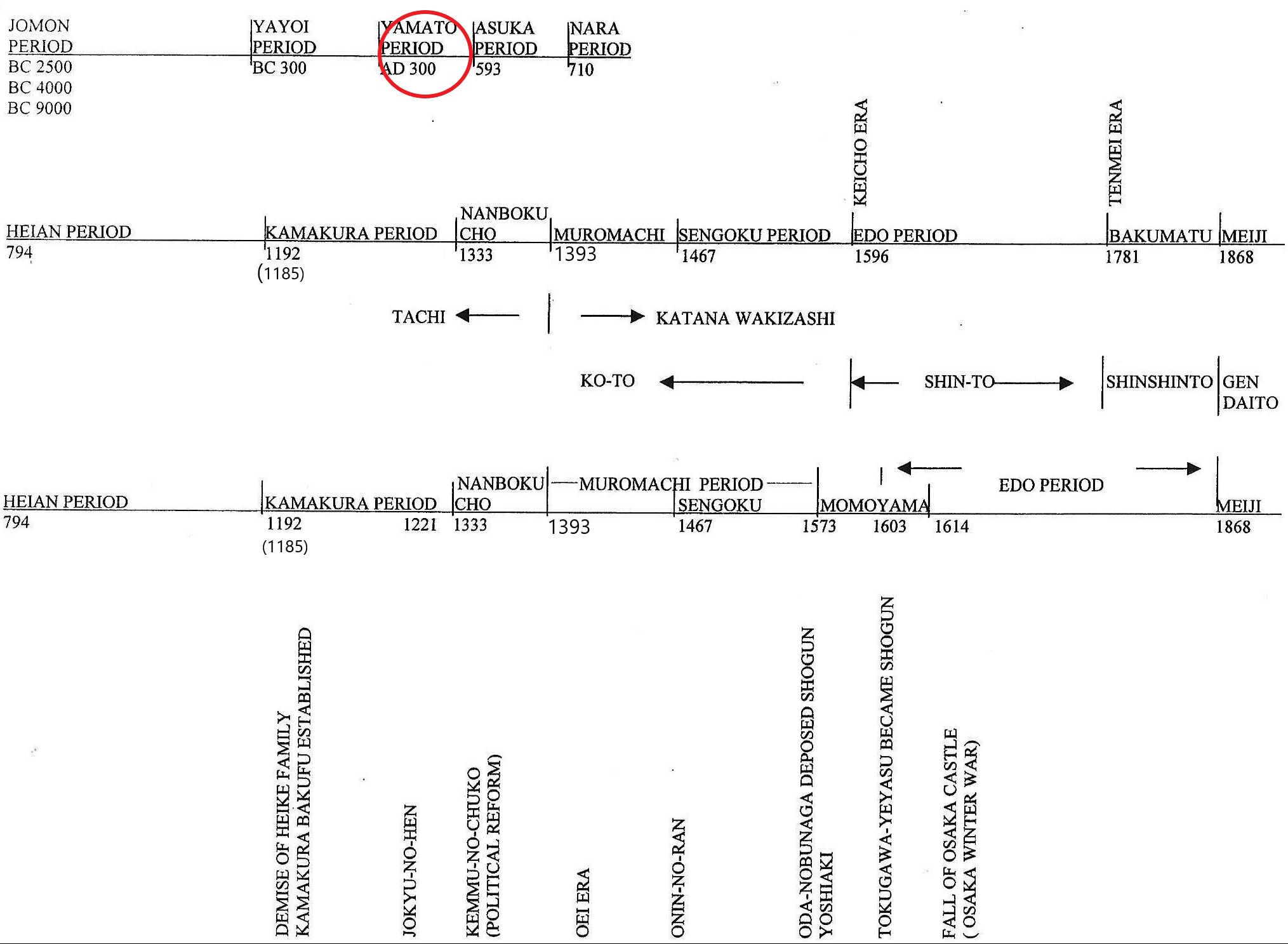

This chapter is a detailed part of Chapter 2, Joko-to (上古刀). Please read Chapter 2 before this section.

The red circle indicates the time we discuss this section.

The Kofun (古墳) culture emerged around the fourth to sixth centuries. Kofun are massive burial sites built for powerful rulers. They are often Zenpo-koen-fun (前方後円墳), meaning the front part is square, and the back is rounded. When viewed from above, their shape resembles a keyhole. The largest kofun is the Nintoku Tenno Ryo (仁徳天皇陵) in Osaka. This is the tomb of Emperor Nintoku. Its size is 480 m X 305 m, and it is roughly 35 meters high. Inside the kofun, we found swords, armor, bronze mirrors, jewelry, iron, and metal tools. Sometimes, iron itself was found. Only the ruling class owned iron because it was considered a precious item at the time. On the outskirts of the kofun, many haniwa*¹ were placed. There are several theories about the purpose of haniwa. One suggests they served as retaining walls, while others say they act as a dividing line between sacred and common areas. There are several more theories.

Originally, haniwa were simple tube shapes. Over time, they became interesting clay figurines, including smiling people, smiling soldiers, dogs with bells around their necks, women with hats, farmers, houses, monkeys, ships, and birds. Some of these were very elaborately made and very cute. Judging by their appearance, people in those times seemed to have worn elaborate clothing. Haniwa figurines are quite popular among children in Japan. We used to have a children’s TV show where haniwa was the main character.

Haniwas suggests what people’s lives were like back then. Their facial expressions are happy and smiling. According to the old Japanese history book Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, the oldest Japanese history book completed during the Nara period), haniwa replaced martyrs, although this has not yet been proven.

At another huge kofun, Ogonzuka Kofun (黄金塚古墳) in Osaka, they discovered swords, bronze mirrors, and other artifacts. Refer to Chapter 2|Joko-to. The writing below is from my college days notebook.

My college professor explained how to determine the age of a specific item by reading partially faded characters on objects, such as a bronze mirror or a sword. For example, there was a sword with a hilt made in Japan and a blade made in China. It had a round hilt and, on it, showed some Chinese characters. It read, “中平[ ]年.” The third letter was not legible. But we knew that the 中平 year was between 184 and 189 A.D., and “年” indicated “year.” Therefore, it was made sometime between 184 and 189. This sword was found in a fourth-century tomb.

He also explained that many nested doutaku (銅鐸)*² had been excavated from various sites. They were discovered nested inside one another. Doutaku was a musical instrument used in rituals. Therefore, scholars believe that people hurriedly hid the doutaku and fled quickly when enemies attacked.

In many countries, excavation can be a time-consuming and tedious process. It often takes a long time to find anything. However, in Japan, it is not as difficult as in other countries. We often discover things. They might not be what you are looking for, but we dig up artifacts quite often.

*ᴵ腰かける巫女 (群馬県大泉町古海出土) 国立博物館蔵 Sitting Shrine Maiden (Excavated from Gunma Prefecture) Owned by National Museum, Public Domain Photo

*² 滋賀県野洲市小篠原字大岩屋出土突線紐5式銅鐸 東京国立博物館展示 Public Domain Photo Dotaku: Excavated from Shiga prefecture Displayed at Tokyo National Museum.