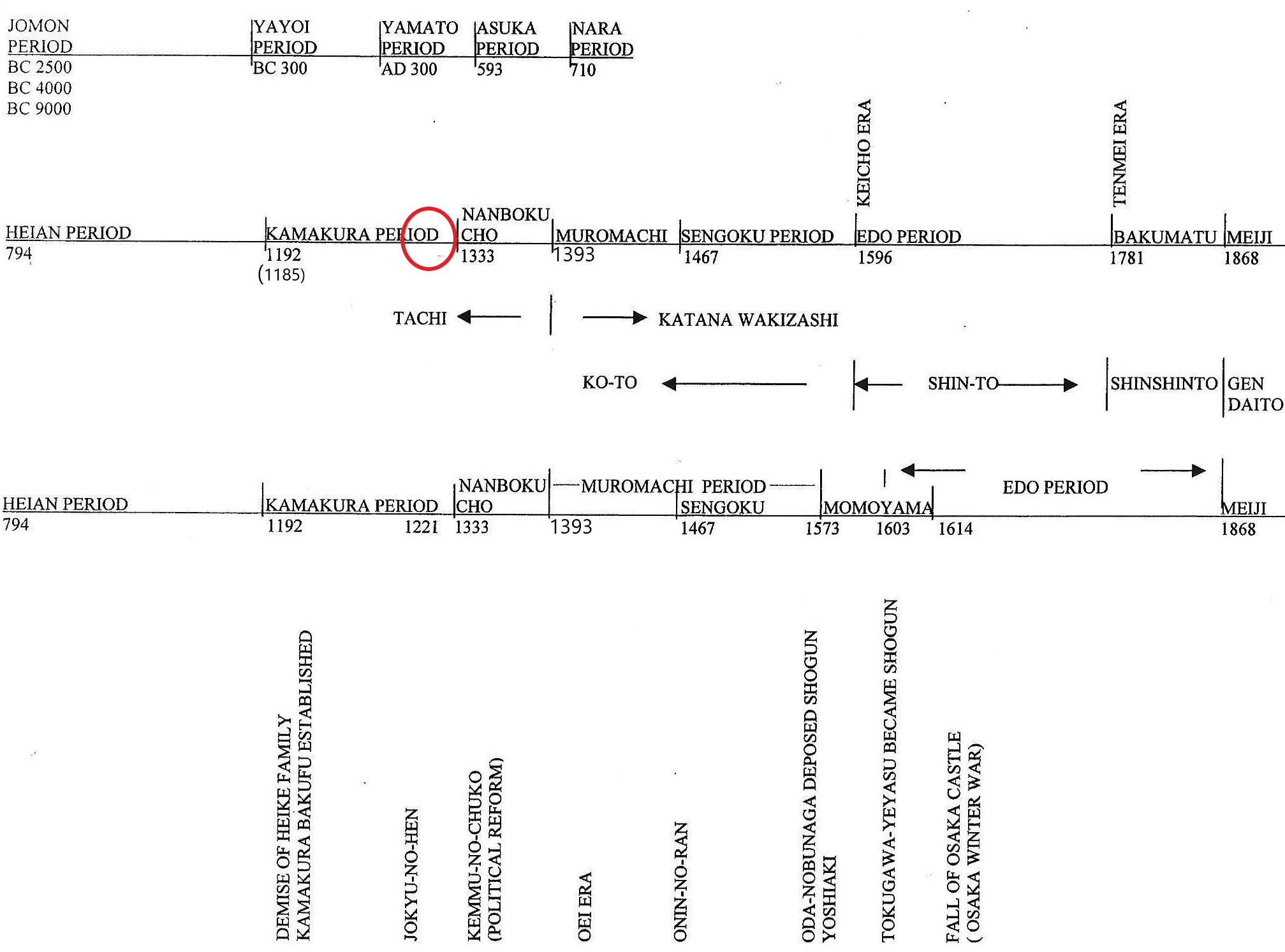

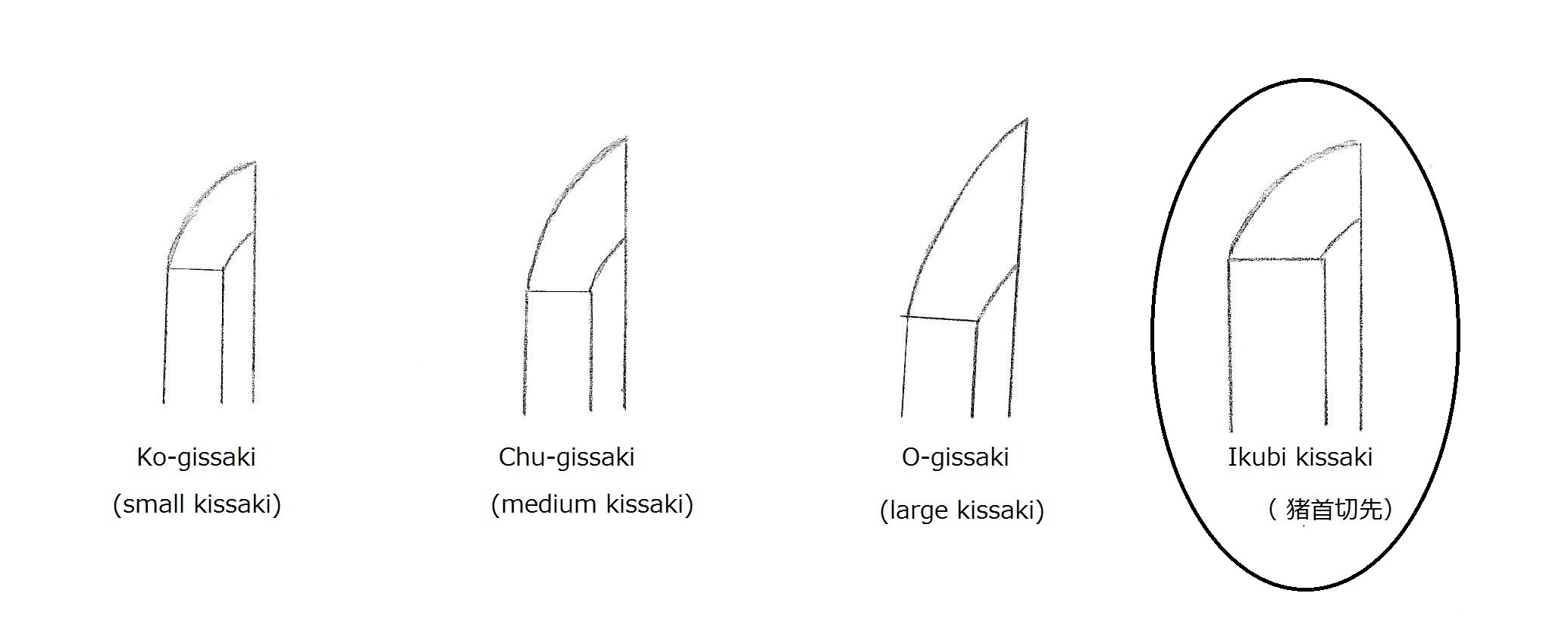

The circle indicates the time we discuss in this section

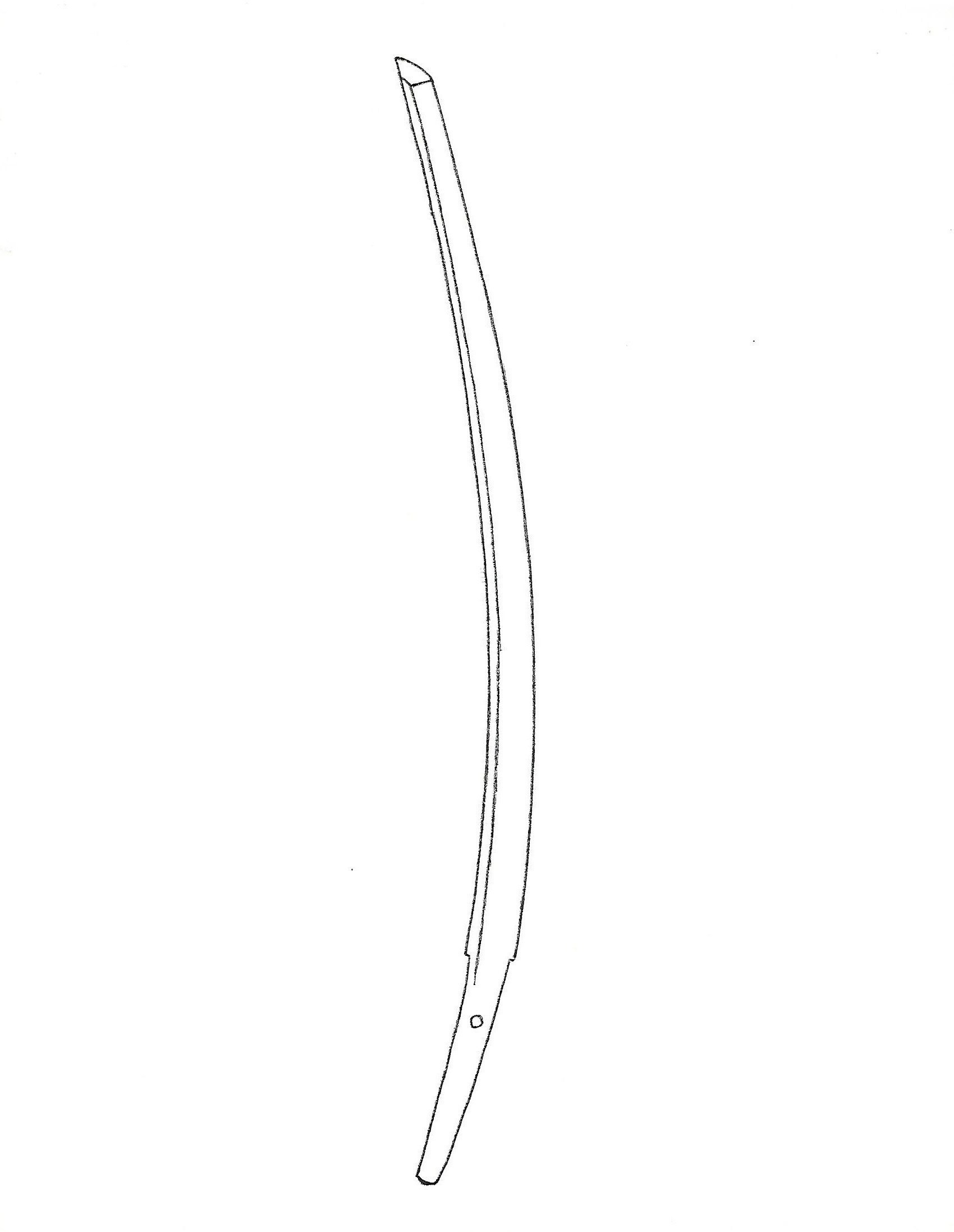

During the Nanboku-cho period, a type of tanto called hirazukuri ko-wakizashi sun-nobi tanto was made. Hirazukuri means flat swords without the yokote line or shinogi. Ko-wakizashi refers to a shorter sword. Sun-nobi tanto means longer than a standard tanto. This type is also known as Enbun Jyoji ko-wakizashi tanto because most of these tantos were created during the Enbun and Jyoji eras of the imperial period. In Japan, a new imperial era begins when a new emperor ascends to the throne. The Enbun era spanned 1356-1361, while the Jyoji period spanned 1362-1368.

Sugata (姿: shape) ————A standard tanto measure is approximately one shaku. Shaku is an old Japanese unit of measurement for length, and one shaku is roughly equal to one foot.

8.5 sun (the sun is another old Japanese measurement unit of length) is approximately ten inches. Ten inches is the standard size for a tanto, known as a josun tanto. Anything longer than a josun tanto is called a sun-nobi tanto. Anything shorter than a josun is called a sun-zumari tanto.

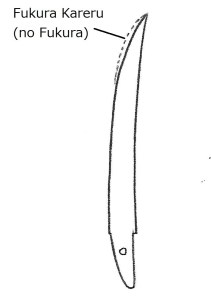

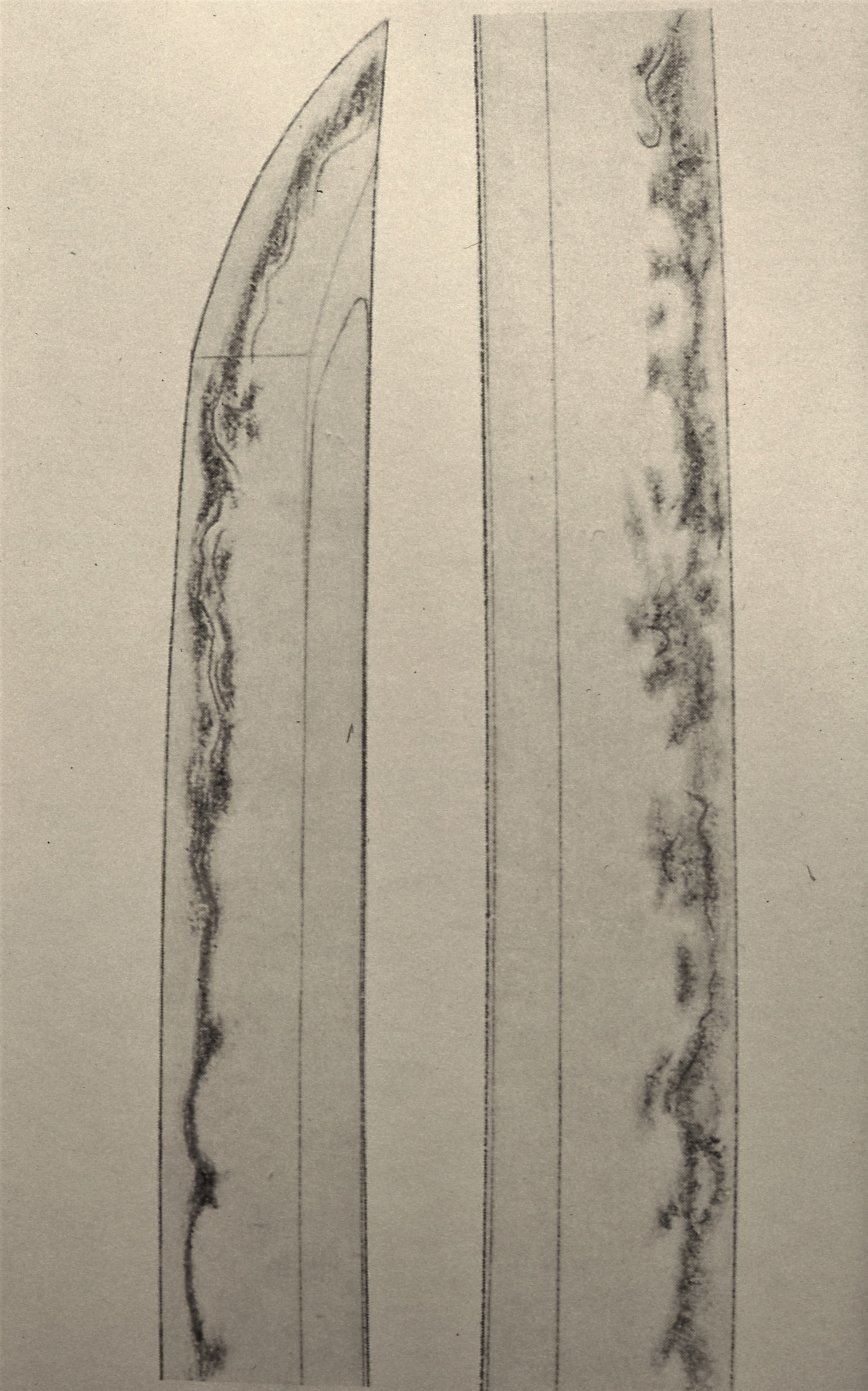

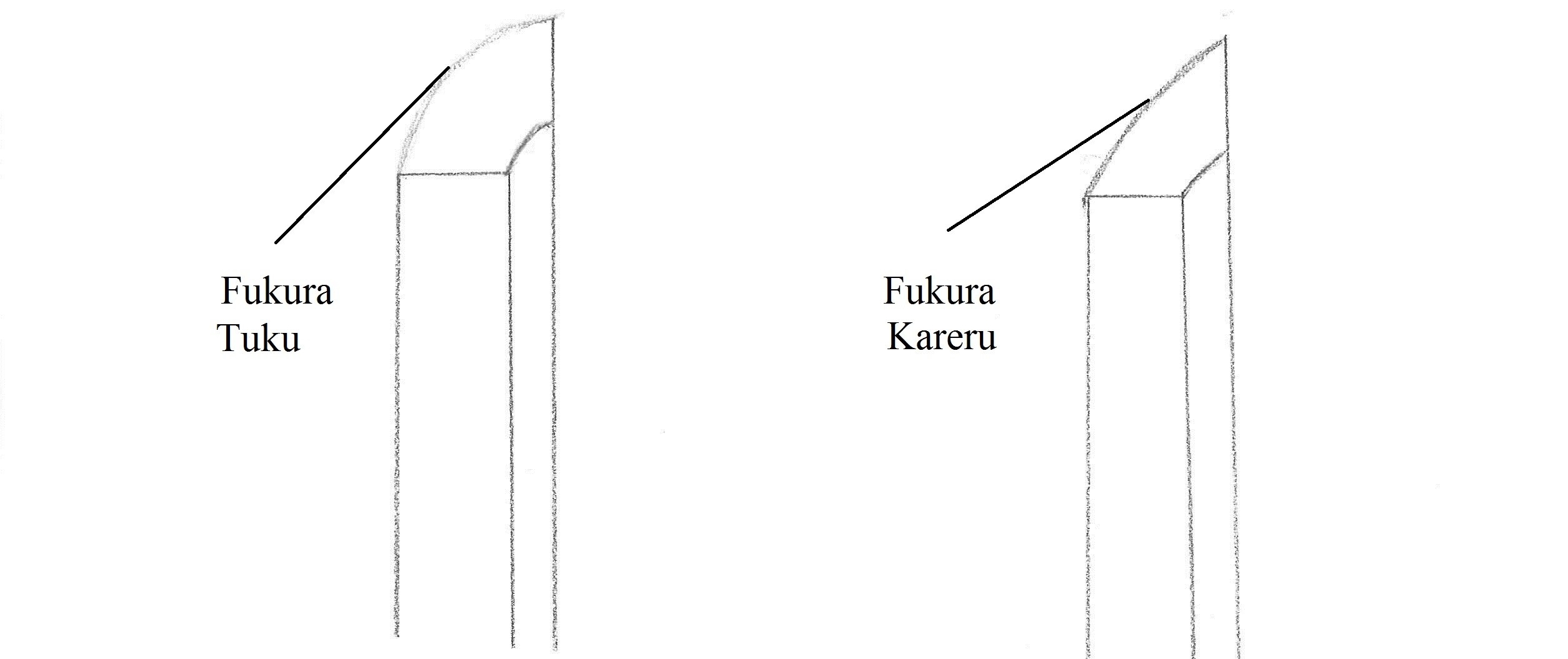

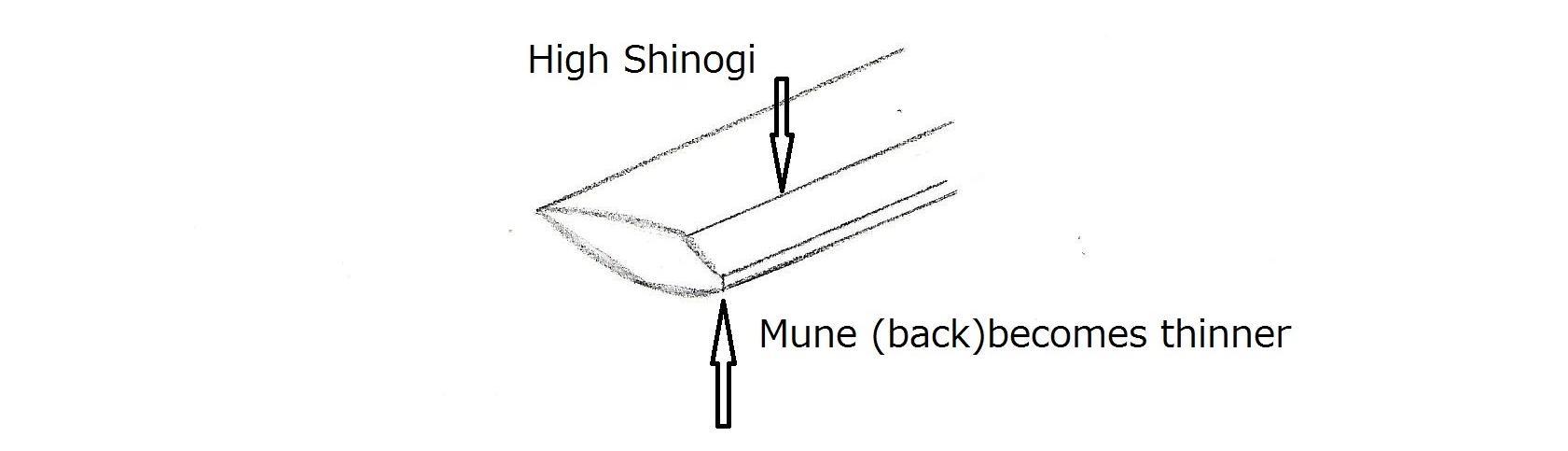

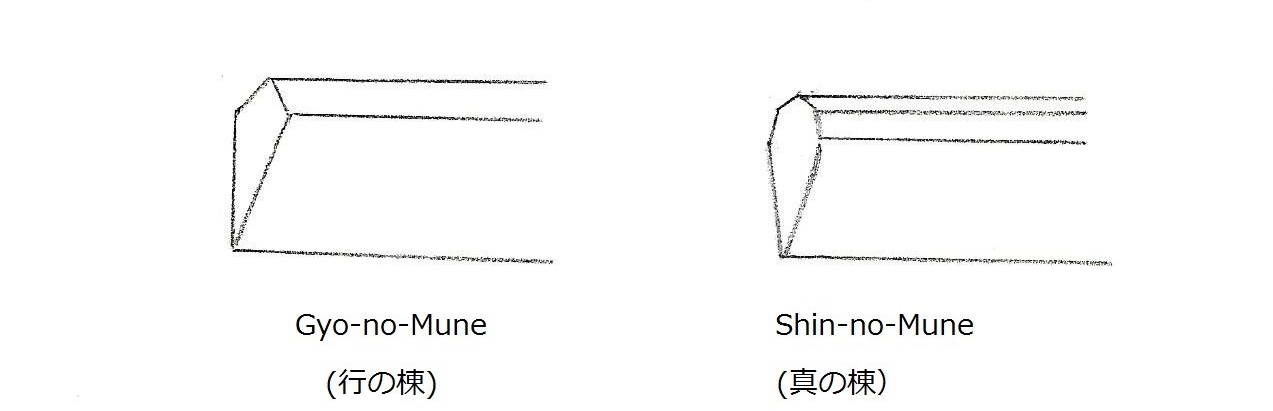

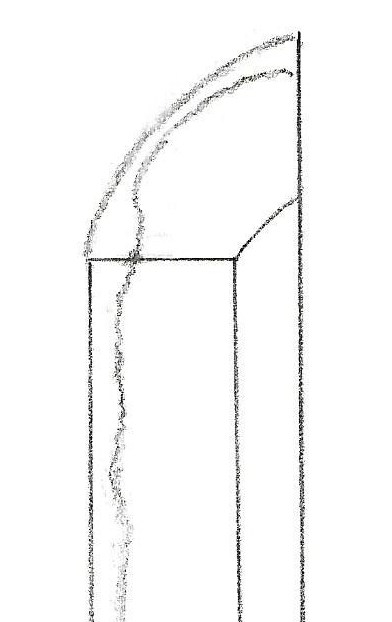

Most of the Nanboku-cho tantos are longer than a josun tanto, approximately one foot two inches. Therefore, they are called hirazukuri ko-wakizashi sun-nobi tanto. Saki-zori (curved outward at the top. See the illustration above). Wide in width and thin in body. Fukura kareru (no fukura means less arc). Shin-no-mune. See the drawing below.

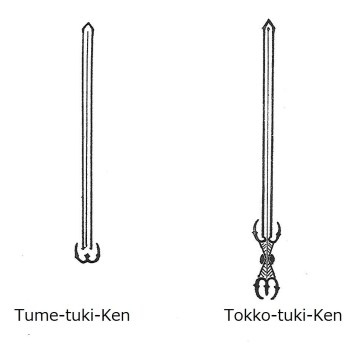

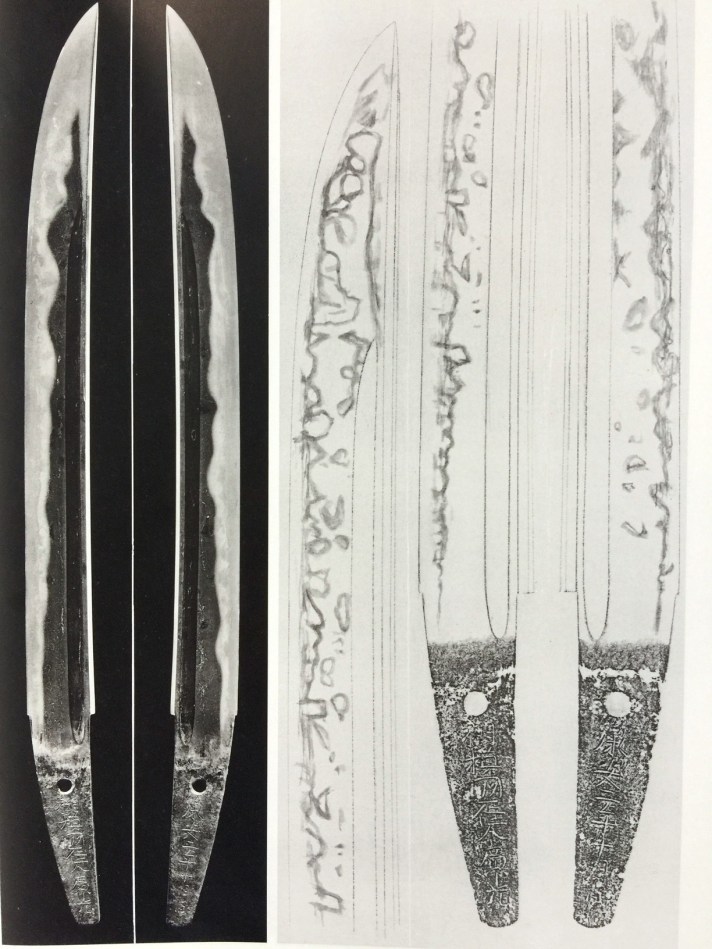

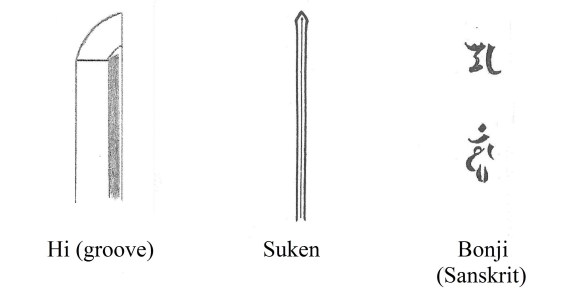

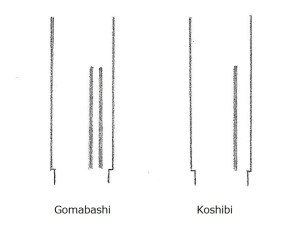

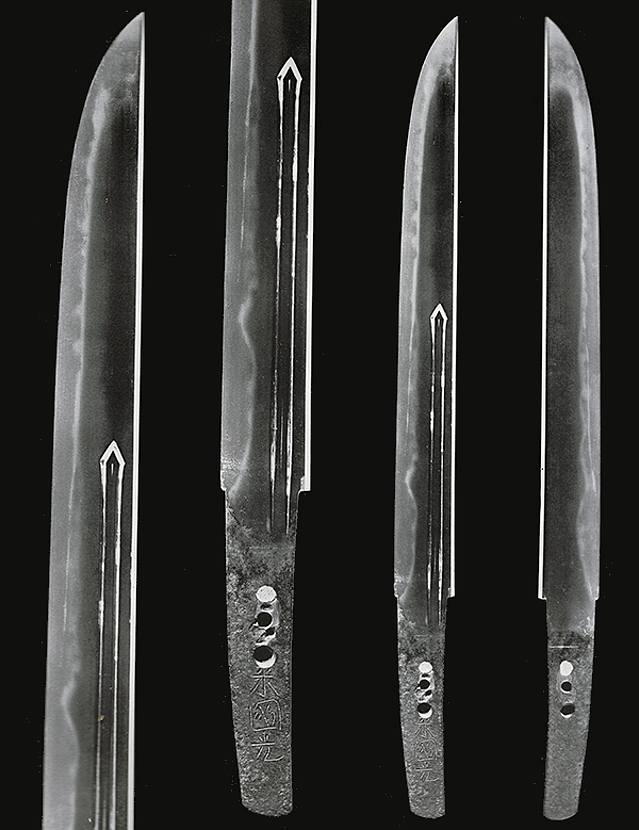

Hi, (樋: Grooves) and Horimono (彫り物: Engraving) ——- A groove or grooves on the mune side. Bonji (Sanskrit, see Chapter 16 Late Kamakura Period (Early Soshu-Den Tanto), koshi-bi (short groove), tumetuki ken, and tokko-tsuki ken (see below) appear. The ken (dagger) is curved widely and deeply in the upper part and shallower and narrower in the lower part. This is called Soshu-bori (Soshu-style carving).

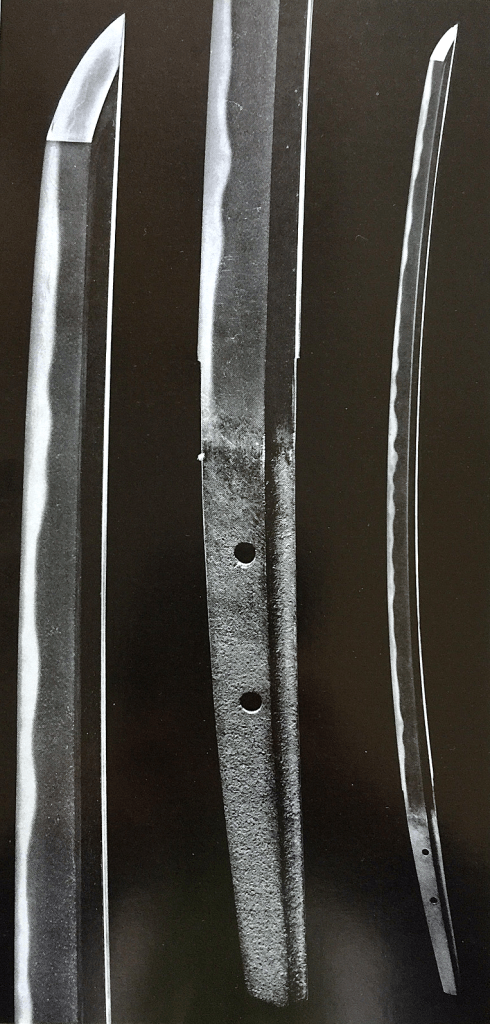

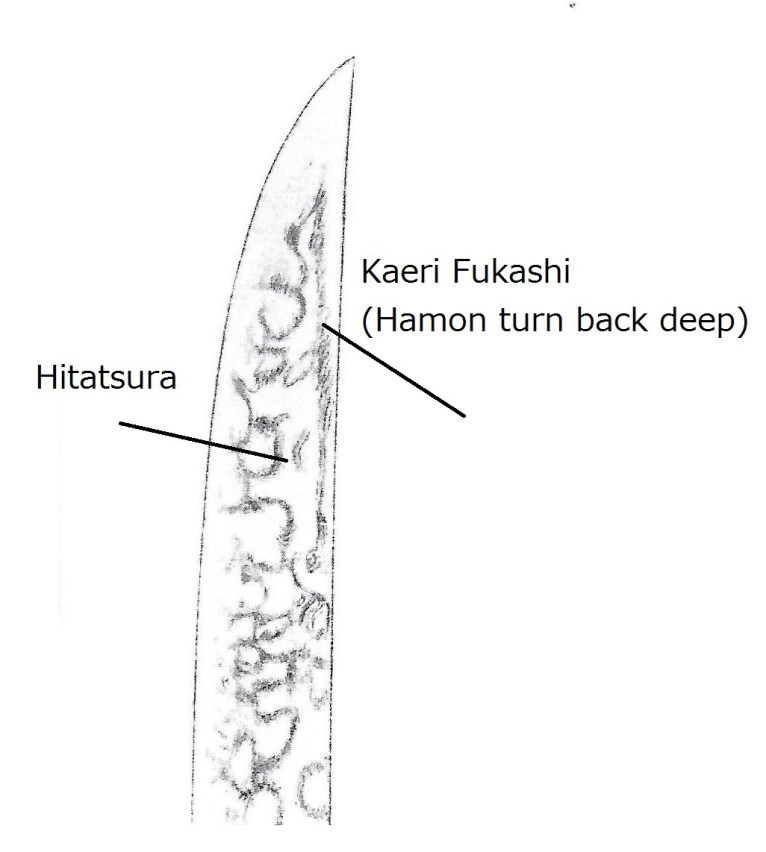

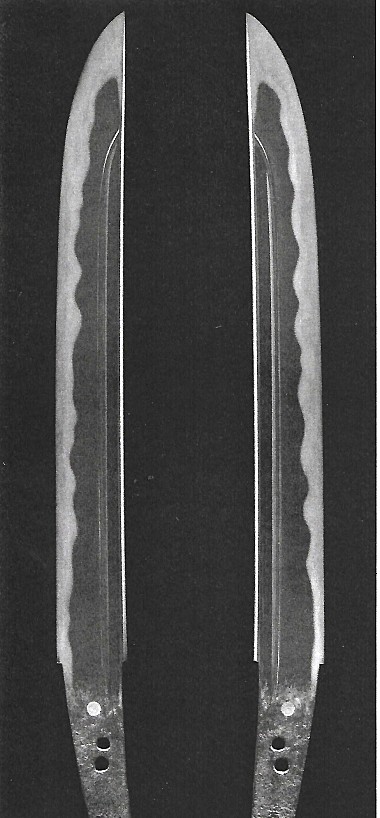

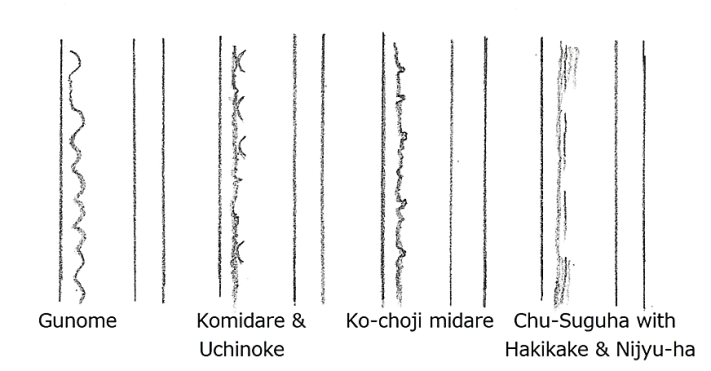

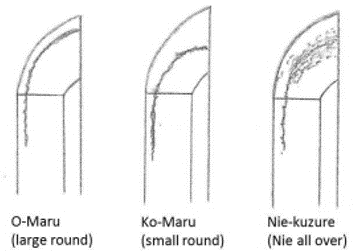

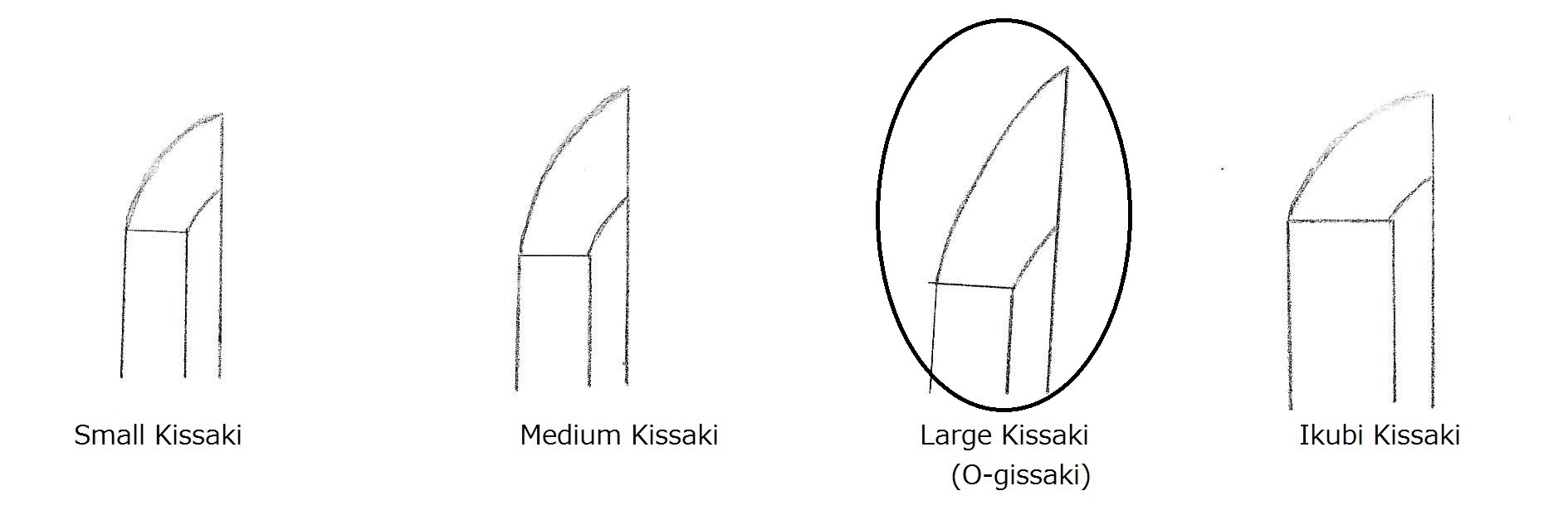

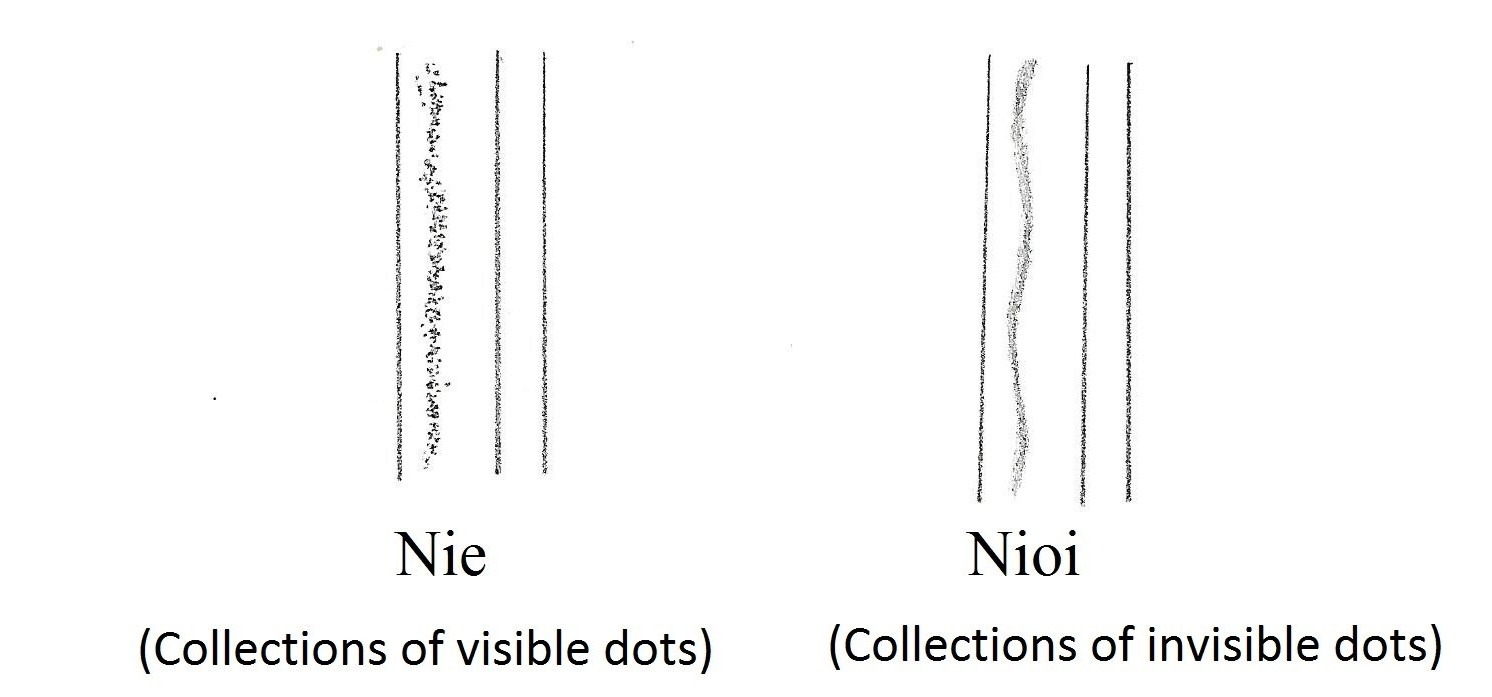

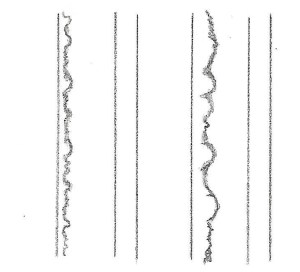

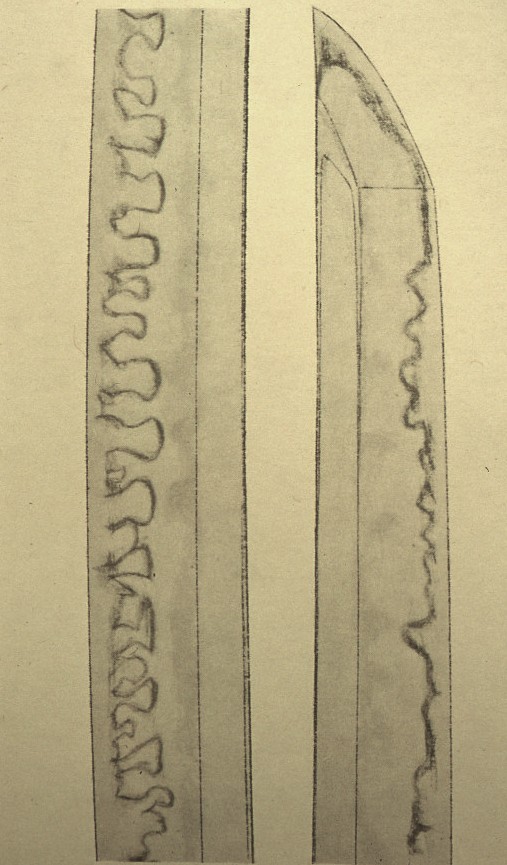

Hamon (刃: Tempered line) ——- The narrowly tempered section at the lower part gradually widens toward the top. A similar wide hamon pattern extends into the boshi area. The hamon in the kissaki area is kaeri-fukashi (deep turn back). See the illustration below. Coarse nie. O-midare (large irregular hamon pattern).

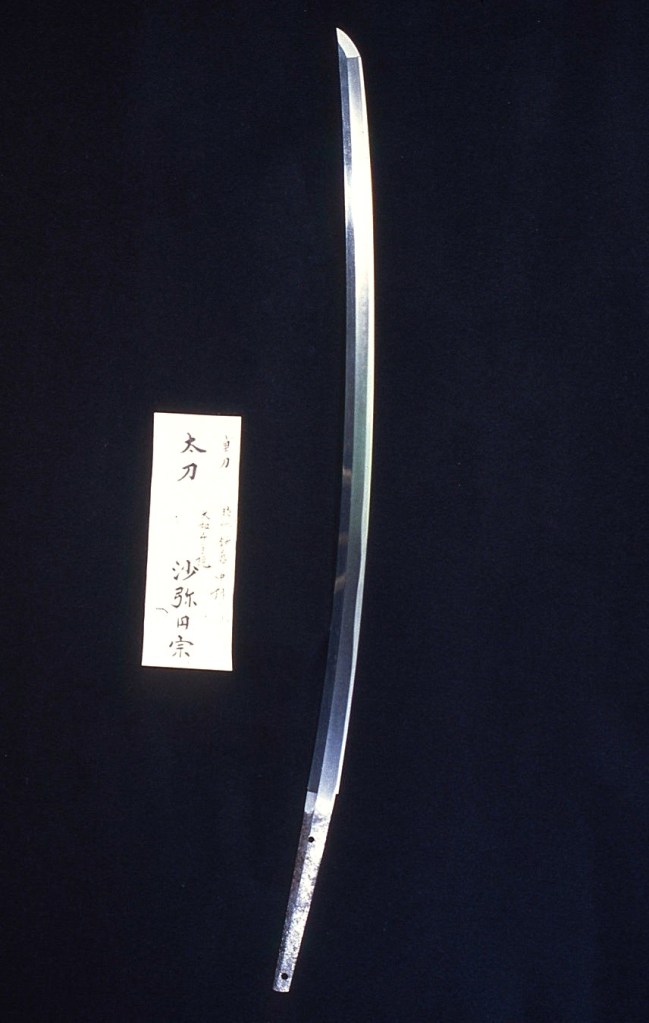

From Sano Museum Catalogue

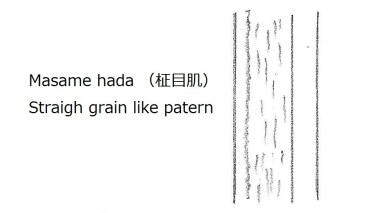

Ji-hada (地肌: the area between shinogi-ji and the tempered line) ——– a loose wood grain pattern called itame. Yubashiri (see Chapter 16, Late Kamakura Period) and tobiyaki (irregular patchy tempered spots) appear. Dense tobiyaki is called hitatsura (see the drawing above).

Nakago (茎: Tang) —- Short tanago-bara. Tanago-bara refers to the shape of the belly of a Japanese fish called tanago (bitterling).

Tanto Swordsmiths during the Nanboku-Cho Period

Soshu Den ———————————————————-Hiromitu( 広光) Akihiro (秋広) Yamashiro Den ————————————————–Hasebe Kunishige (長谷部国重) Bizen Den ——————————————————— Kanemitu (兼光) Chogi (長義 )

Soshu Hiromitsu “Nippon-To Art Sword of Japan “ The Walter A. Compton Collection

Soshu Hiromitsu “Nippon-To Art Sword of Japan “ The Walter A. Compton Collection

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted) The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

来国光(Rai Kunimitsu)

来国光(Rai Kunimitsu)

Kawazuko-choji O-choji Ko-choji Suguha-choji (tadpole head) (large clove) (small clove) (straight and clove)

Kawazuko-choji O-choji Ko-choji Suguha-choji (tadpole head) (large clove) (small clove) (straight and clove)

Sansaku-boshi

Sansaku-boshi

Osafune Nagamitsu(長船長光) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Osafune Nagamitsu(長船長光) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

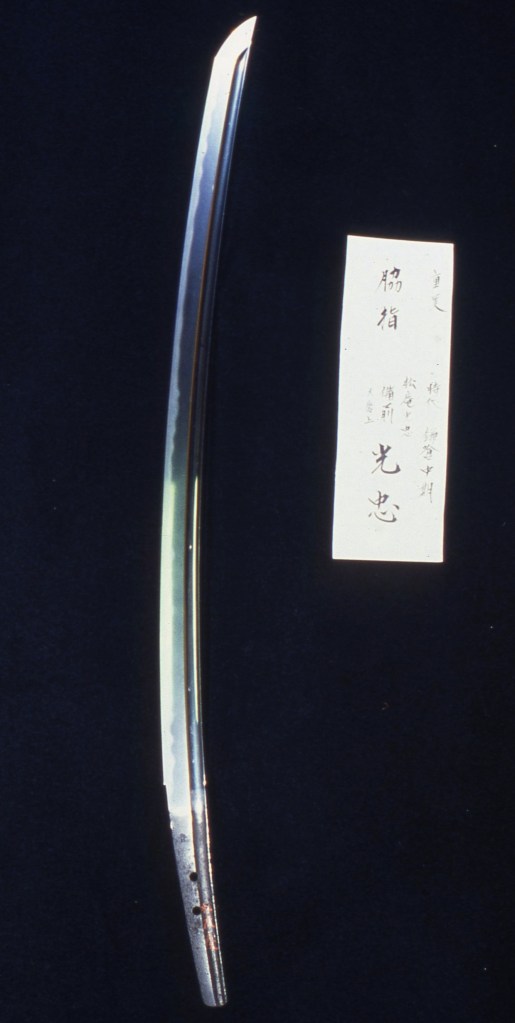

Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠) Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠)

Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠) Osafune Mitsutada(長船光忠)

The tomb of Minamoto-no-Yoritomo. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.

The tomb of Minamoto-no-Yoritomo. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.