Chapter 57 is a detailed section of Chapter 23, Sengoku Period Sword. Please read Chapter 23, Sengoku Period Sword, before reading this part.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

During the Sengoku period (Warring States era), the Mino-den and Bizen Osafune groups were the leading sword makers. For nearly 100 years during the Warring States period, all daimyo needed numerous swords. Having suppliers nearby was more advantageous. Many Sengoku daimyo (戦国大名: warlords) could easily access the Mino region because of its central location. Since the Heian period, Mino swordsmiths have been producing swords there. One of the well-known swordsmiths of Mino-den at the end of the Kamakura period was Shizu Kane’uji (志津兼氏). He was one of the Masamune juttettu (正宗十哲)*. However, the true peak of the Mino-den came during the Sengoku period. During the Sengoku period, the Shizu and Tegai groups from the Yamato region, and swordsmiths from the Yamashiro area, moved to Mino. Mino became the busiest center for sword-making, producing practical swords for feudal lords.

*Masamune Juttetsu (正宗十哲) ———-The original meaning of Masamune Juttetsu was the top 10 Masamune students. However, the term was later used more broadly. Masamune Juttetsu (正宗十哲):https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/7194/

Three examples of Sengoku period swords

The three swords listed below are examples of swords from the Sengoku period. Note that each sword is unique. Even when the same swordsmith forged swords, each one is different. Please refer to Chapter 23, Sengoku Period Sword, for the key characteristics of swords made during the Sengoku period.

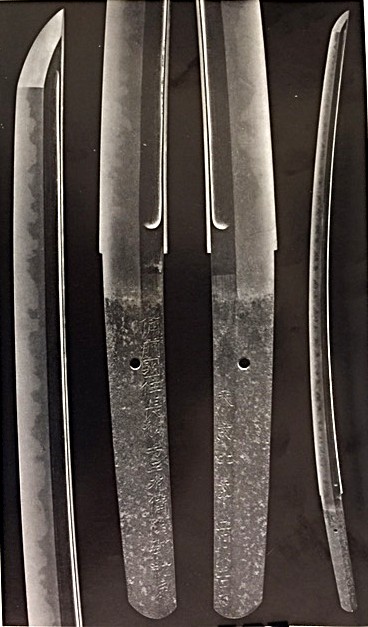

Bizen Osafune Yosozaemon Sukesada (備前国住長船与三左衛門尉祐定) from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted).

Bizen Osafune Yosozaemon Sukesada (備前国住長船与三左衛門尉祐定) from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted).

Characteristis on the sword above

Hamon is Kani-no-tsume (crab-claw pattern; see the hamon above). The Kani-no-tsume pattern hamon never appeared during the Heian, Kamakura, or Nanboku-cho periods. This type of hamon is one of the key factors in determining whether a sword is from the Sengoku Period. Marudome-hi (the end of the groove is rounded) often appears on Bizen-den swords during the Sengoku period. Wide tempered area. The midare-komi boshi (where the hamon on the body and the boshi share the same pattern) has a long turn-back that stops abruptly. The hamon has a nioi base, and most Bizen swords feature nioi, though a few exceptions exist.

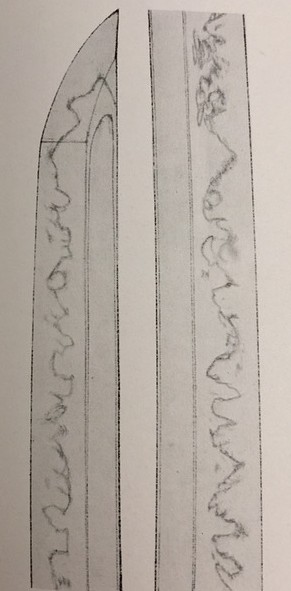

Izuminokami Fujiwara Kanesada (和泉守藤原兼㝎) from Sano Museum Catalog

Izuminokami Fujiwara Kanesada (和泉守藤原兼㝎) from Sano Museum Catalog

Characteristic on the sword above

The last character of the kanji (Chinese characters) in the swordsmith’s name above is “㝎.” We use this uncommon character instead of the standard “定” for him. Because there are two Kanesada. To distinguish him from the other Kanesada (兼定), we use the character “㝎 “and call him Nosada “のさだ.”

Izuminokami Fujiwara Kanesada (AKA Nosada) was the leading swordsmith of Mino-den during that time. The sword’s shape is typical of the Sengoku period: shallow curvature, a chu-gissaki (medium-sized kissaki), and a pointed gunome hamon. The hamon width can be wide and narrow. Nosada and other Mino-den swordsmiths often exhibit wood-grain patterns with masame on the ji-hada. Nioi base, mixed with coarse nie.

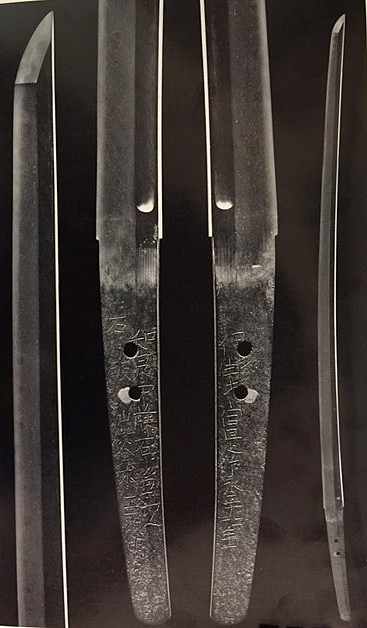

Bizen Osafune Norimitsu (備前長船法光) from Sano Museum Catalog, permission granted.

Bizen Osafune Norimitsu (備前長船法光) from Sano Museum Catalog, permission granted.

Characteristic of the sword above

Shallow curvature. Sturdy appearance. Marudome-hi (the hi ends are rounded). The pointed hamon is called togari-ba (尖り刃). Nioi base, mixed with nie. Slight masame and wood grain patterns on Ji-hada.

Part of the Burke Album, a property of Mary Griggs Burke (Public Domain). Paintings by Mitsukuni (土佐光国), 17th century. The scenes are based on “The Tales of Genji.“

Part of the Burke Album, a property of Mary Griggs Burke (Public Domain). Paintings by Mitsukuni (土佐光国), 17th century. The scenes are based on “The Tales of Genji.“