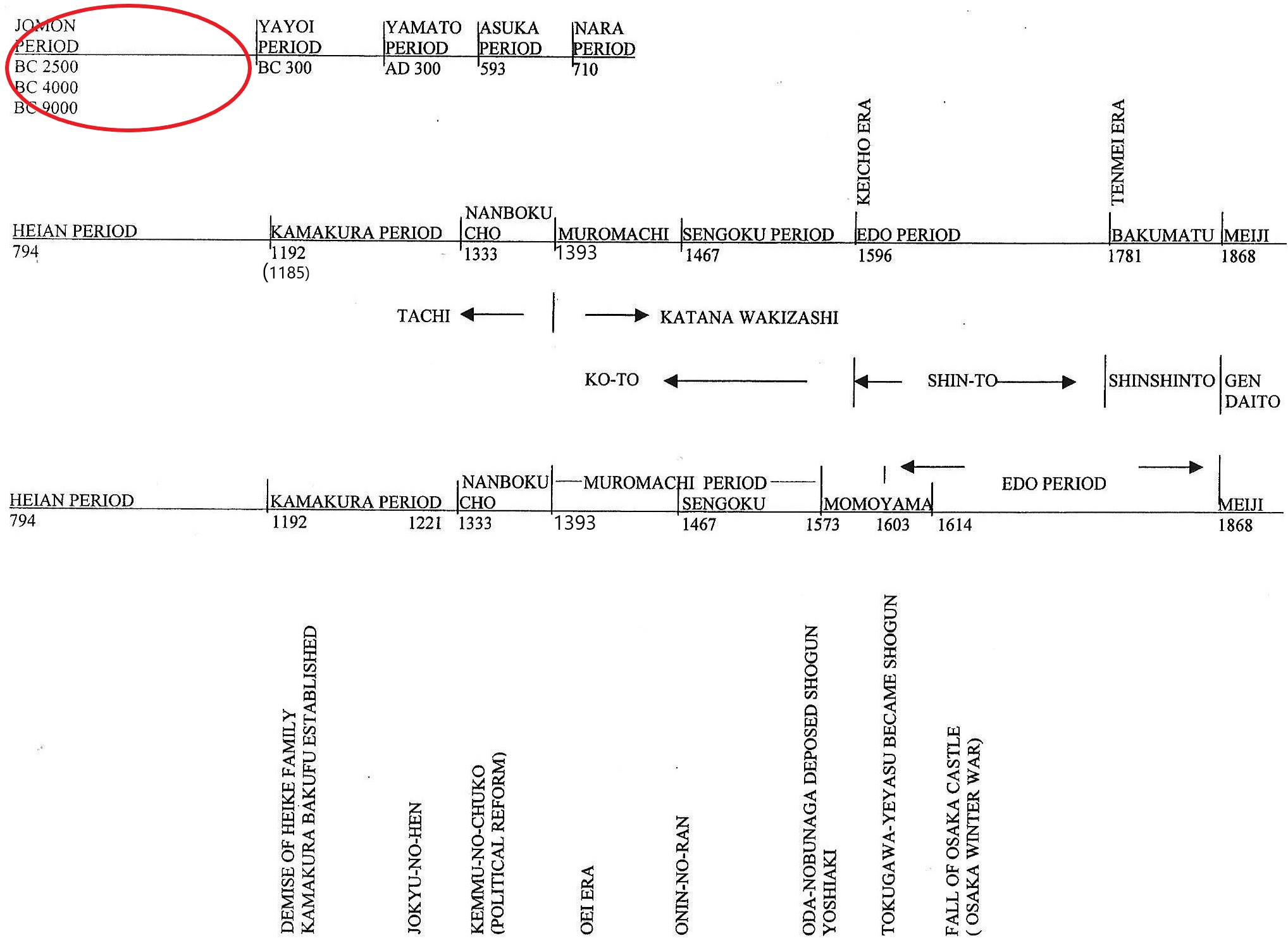

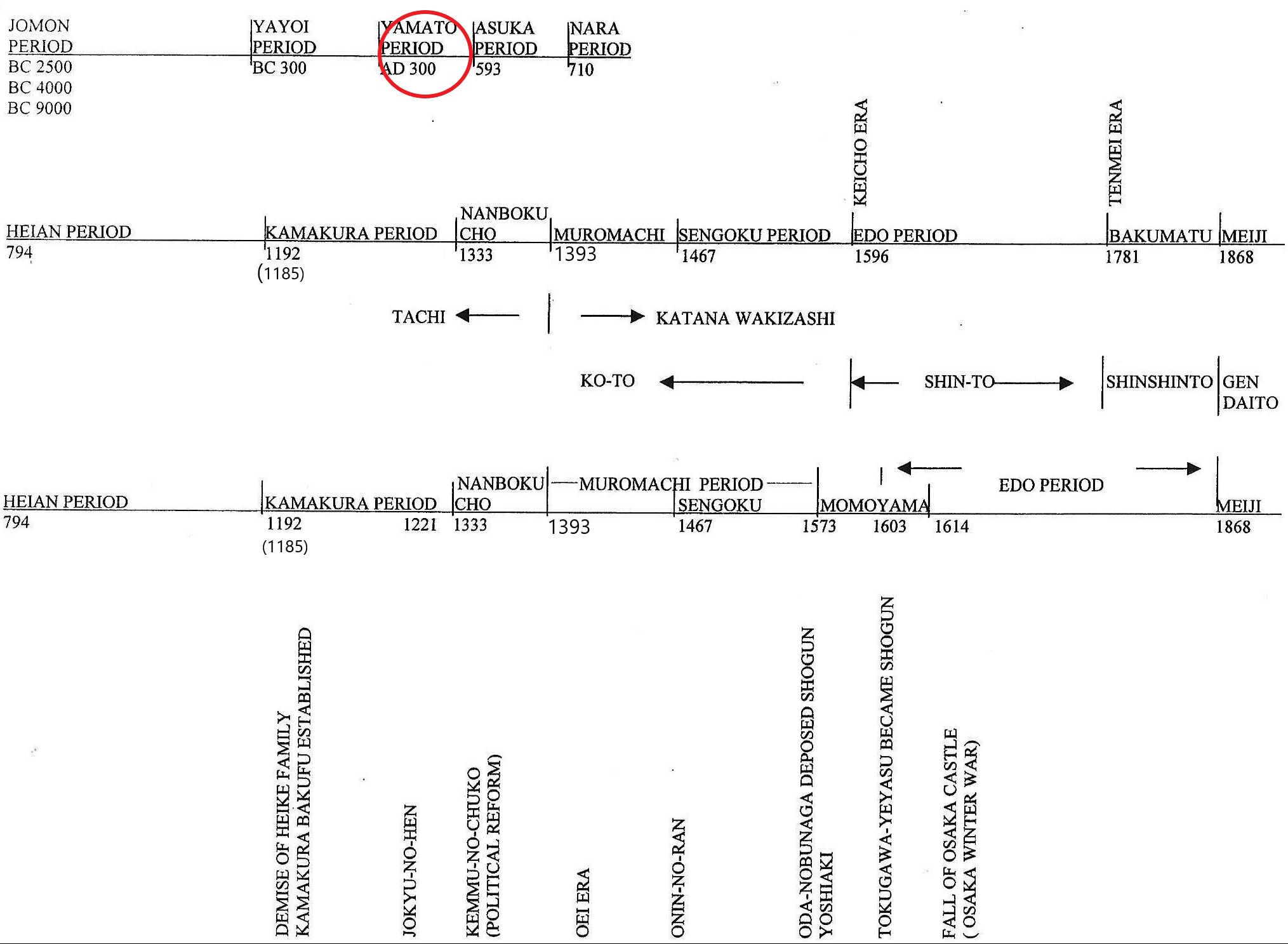

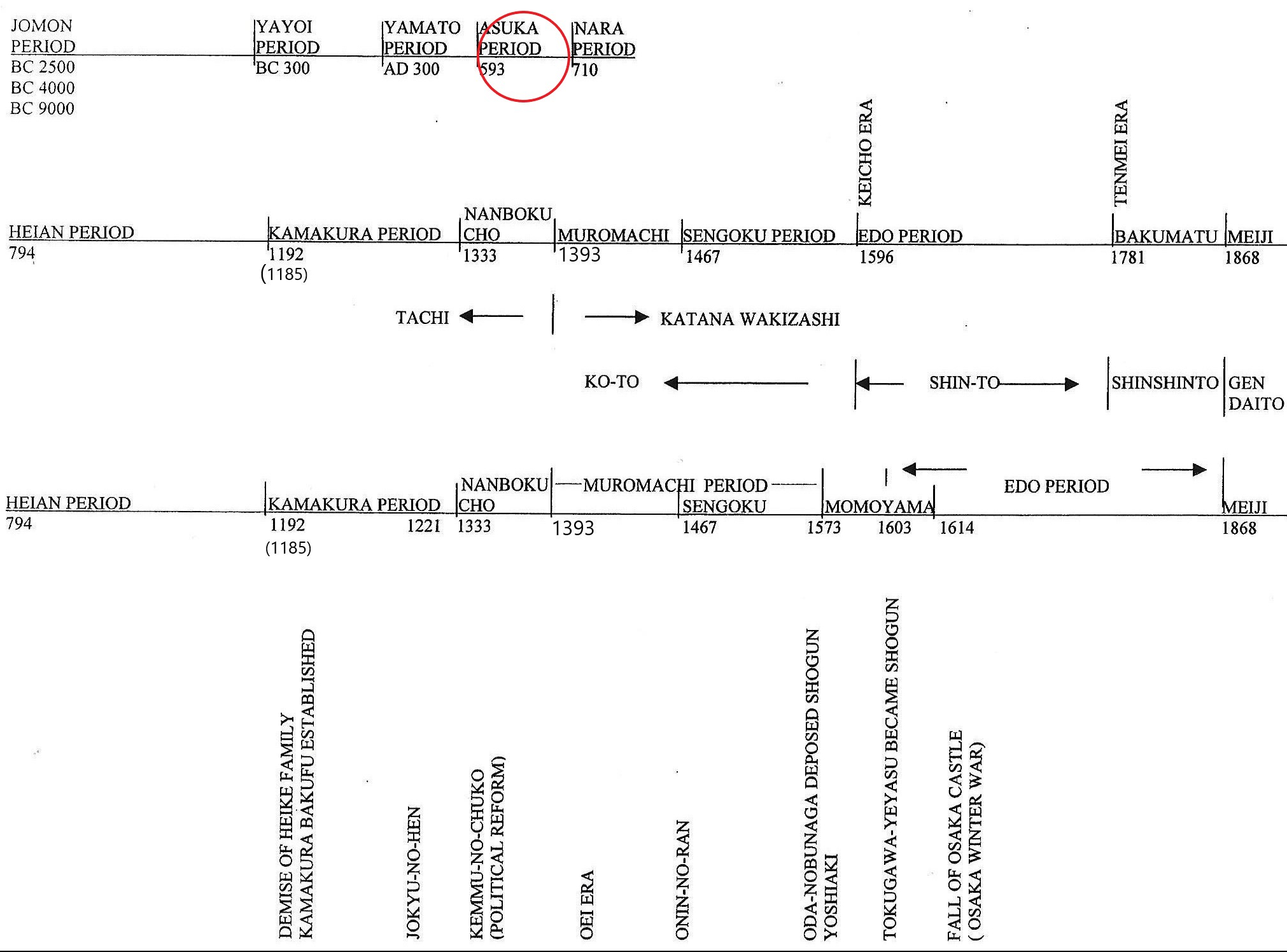

Joko-to refers to swords made before the Heian period. Joko-to is not part of sword study. The study of swords begins from the Heian period. Joko-to falls under the category of archaeology.

Jomon (縄文) period 9000 B.C.

The Jomon period dates back to 9000 B.C. This is between the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods. The characteristic of this time was the rope design (jomon 縄文) seen on their earthenware.

A stone sword from this period was discovered. It is a single piece, approximately 27 to 31 inches (70 to 80 cm) long. This is not a Neolithic scraper. This item was made for ceremonial purposes.

Yayoi (弥生) period 300B.C to 300A.D (approximately)

Around 300 B.C., the Yayoi culture replaced the Jomon culture. Characteristics of the Yayoi culture are shown on their earthenware. They were rounder, smoother, and softer in design, and their techniques had greatly improved since the Jomon period. They are called the Yayoi culture because objects from this era were unearthed in the Yayoi-cho area (the name of the place) near Tokyo University in Tokyo. They also discovered bronze artifacts, including a bronze sword (doken 銅剣), a bronze pike (do-hoko 銅矛), bronze mirrors (do-kyo 銅鏡), and bronze musical instruments (do-taku 銅鐸). These items were imported from China and Korea, but the Japanese began making their own bronze items in the late Yayoi period. Although iron artifacts are rarely found, evidence indicates that iron objects already existed at that time.

Himiko(卑弥呼)

It is said that, according to the Chinese history book “Gishi Wajinden” (魏志倭人伝), around 300 A.D., there was a country called Yamataikoku (邪馬台国) that controlled about thirty small domains in Japan. The country’s leader was a female figure named Himiko (卑弥呼), a shaman maiden. She sent a messenger to the Chinese dynasty in 239 A.D., and she was given the title of head of Japan (親魏倭王), along with a bronze mirror and a long sword (five feet long). Today, we still do not know the exact location of Yamataikoku. This Chinese history book, “Gishi Wajinden” (魏志倭人伝), explains how to reach Yamataikoku, but if we follow the book’s directions exactly, we end up in the middle of the ocean, south of Kyushu (九州). We still have a big debate over the exact location of Yamataikoku.

Yamato (大和) period 300 A.D. — 593 A.D

At the end of the Yayoi period, Japan was divided into small regions. These regions were ruled by local clans called Go-zoku(豪族). Around 400 A.D., the most powerful Go-zoku united the country and named it Yamato-chotei (大和朝廷). This was the first Japanese imperial court, the origin of the current Japanese imperial family. They were powerful enough to construct the enormous tombs called kofun (古墳) for themselves. One of the famous kofun, Ogonzuka kofun (黄金塚古墳) in Osaka, contained swords among other items. The sword’s hilt was made in Japan, while the blades were made in China. On the surface of the hilt, they depicted a house design. Other items found in the kofun include armor, mirrors, iron tools, and jewelry. Outside the kofun, it was common practice to place haniwa (clay figurines). These haniwa included smiling people, animals, houses, soldiers with swords, and sometimes simple tube-shaped haniwa (埴輪). We believe they placed haniwa as retaining walls or as a dividing line for the sacred area. Based on the writings on the backs of mirrors and swords, kanji (Japanese characters) were used around the fifth to sixth century.

Asuka (飛鳥) period 593 —710

At the end of the Yamato period, after a long power struggle, Shotoku Taishi (聖徳太子) became regent in 593 (beginning of the Asuka period). Shotoku Taishi established the political system and created Japan’s first constitution (憲法17条). He promoted and encouraged Buddhism and built the Horyuji Temple (法隆寺) in Nara. The image of Shotoku Taishi appeared on 10,000-yen bills for many years. During the Asuka period, we see kanto tachi (環頭太刀), characterized by a ring-shaped hilt. Kan (環) means ring, and to (頭) means head. Also, on the ring-shaped hilt, there are inscriptions, such as the emperor’s name, the location, and numerals. The numbers indicate the years when the specific emperor was enthroned. All of these were straight swords.

Hilt of a Japanese straight sword. Circa 600 AD. From Wikipedia Commons, the free media repository

Hilt of a Japanese straight sword. Circa 600 AD. From Wikipedia Commons, the free media repository

Nara (奈良) period 710 —794

In 710, the capital city was moved to Nara, known as Heijo-kyo (平城京). The shape of the Joko-to was straight, usually measuring 25 inches (60 –70 cm) in length. It was suspended from a waist belt. Some swords originated from China, while others were made in Japan. Many swords were found in Kofun and Shoso-in (正倉院) during the Nara period. Shoso-in is a storage building where Emperor Shomu’s (聖武天皇) belongings were stored. Among other items, 55 swords were found there. These swords are called warabite-tachi. Warabi (Bracken) is the name of an edible wild plant native to Japan. These swords are called warabite-tachi because the shape of the hilt resembles warabi, whose stem curls up at the top.

The photo is from Creative Commons, a free media source for online pictures

The photo is from Creative Commons, a free media source for online pictures