This chapter is a detailed part of Chapter 15, Revival of Yamato Den. Please read Chapter 15 before reading this section.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

At the end of the Kamakura period, powerful temples expanded their territories in the Yamato region. Refer to the map below for the location of the Yamato region. Several prominent temples, especially those with large territories, held political and military power to control the area at the end of the Kamakura period. These large territories were called shoen (荘園). They employed many monk soldiers known as so-hei. The demand for swords increased because of the rising number of Sohei (僧兵). This increased demand revived the Yamato–den.

Some prominent temples had their own swordsmiths within their territories. Todaiji Temple (東大寺) supported the Tegai (手掻) sword group. The Senjuin (千手院) sword group lived near Senju-do (千手堂), where Senju Kannon (千手観音) is enshrined. The Taima sword group originated from the Taima-ji Temple (当麻寺). The Shikkake group (尻懸) and the Hosho group (保昌) were also part of the Yamato-den sword groups. These five groups are known as Yamato Goha (the Yamato five groups).

General Characteristic of Yamato Den

The Yamato-den (大和伝) sword always shows masame (柾目: straight grain-like pattern) somewhere on the ji-hada, ji-gane, or hamon. Refer to Chapter 15, Revival of Yamato Den. Masame is sometimes mixed with mokume (burl-like pattern) or itame (wood-grain-like pattern). Either way, Yamato-den always shows masame somewhere. Some swords display masame across the entire blade, while others show less. Because of the masame, the hamon often shows sunagashi (a brush stroke-like pattern) or a double line called niju-ha.

Taima (or Taema) group (当麻)

- Shape ———————– Middle Kamakura period style and Ikubi-kissaki style

- Hamon ———–Mainly medium Suguha. Double Hamon. Suguha mixed with Choji. Often shows Inazuma and Kinsuji, especially Inazuma appear under the Yokote line.

- Boshi ————————- Often Yakizume. Refer Yakizume on 15| The Revival of Yamato Den(大和伝復活)

- Ji-hada ——————– Small wood grain pattern and well-kneaded surface. At the top part of the sword, the wood grain pattern becomes Masame.

Shikkake Group (尻懸)

- Shape —————- Late Kamakura period shape. Refer 14| Late Kamakura Period: Sword (鎌倉末太刀)

- Hamon ————————- Mainly Nie (we say Nie-hon’i). Medium frayed Suguha, mixed with small irregular and Gunome (half-circle pattern). A double-lined, brush-stroke-like Pattern may appear. Small Inazuma and Kinsuji may also be shown.

- Boshi ———————— Yakizume, Hakikake (bloom trace like pattern) and Ko-maru (small round)

- Ji-hada ———- Small burl mixed with Masame. The Shikkake group sometimes shows Shikkake-hada (the Ha side shows Masame, and the mune side shows burl.)

Tegai Group ( 手掻 )

- Shape —— Early Kamakura style with thick Kasane (body). High Shinogi. Koshizori.

- Hamon ————- Narrow tempered line with medium Suguha hotsure (frayed Suguha). Mainly Nie. Double tempered line. Inazuma and Kinsuji may show.

- Boshi ————————————— Yakizume (no turn back), Kaen (flame-like).

- Ji-Hada ————————————————— Fine burl mixed with Masame.

Tegai Kanenaga of Yamato. From the Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted). The illustration (called Oshigata) shows notare (wave-like hamon) and suguha-hotsure (frayed suguha pattern) with kinsuji.

My Yamato sword: Acquired at the Annual San Francisco Swords Show.

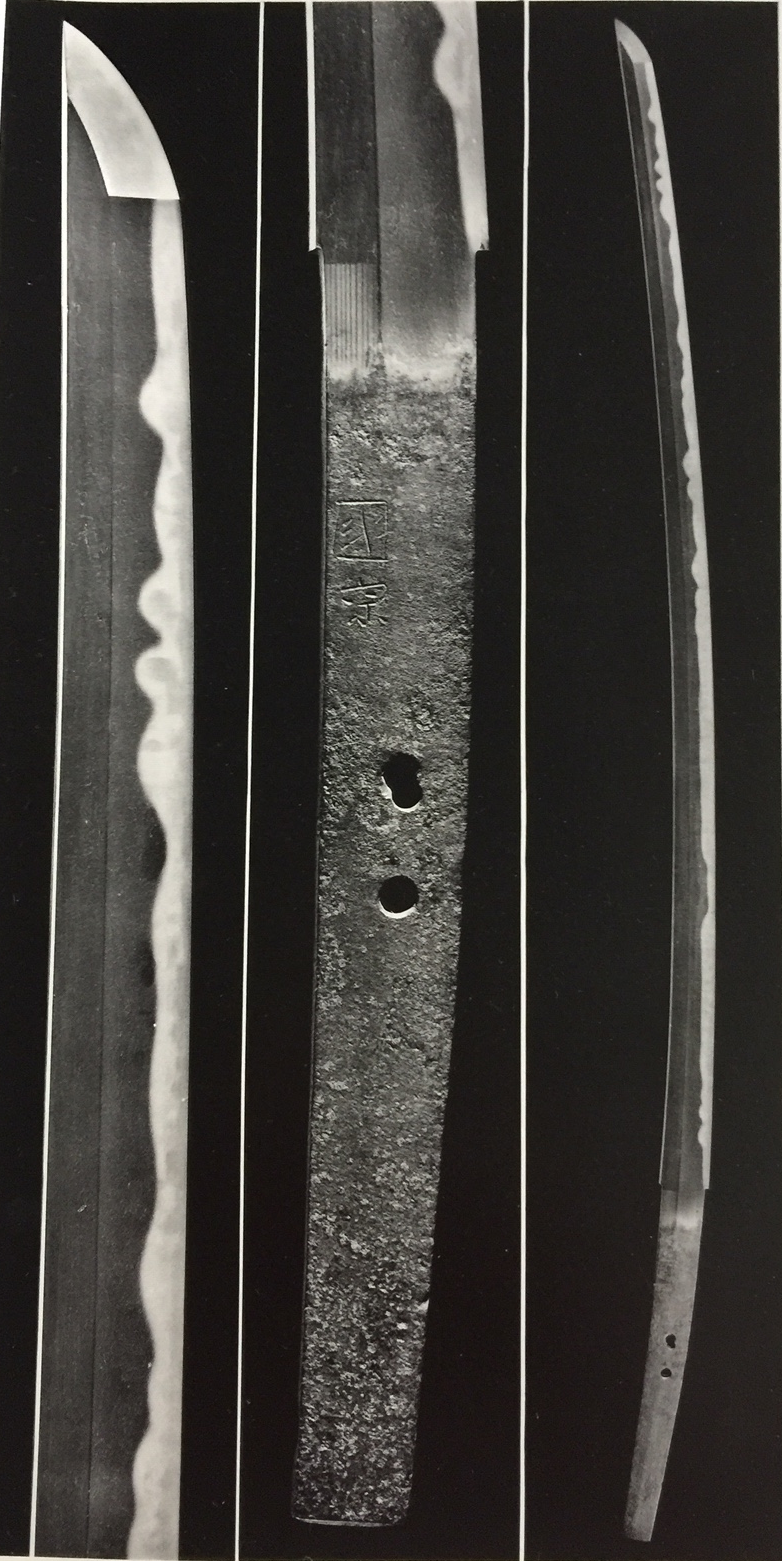

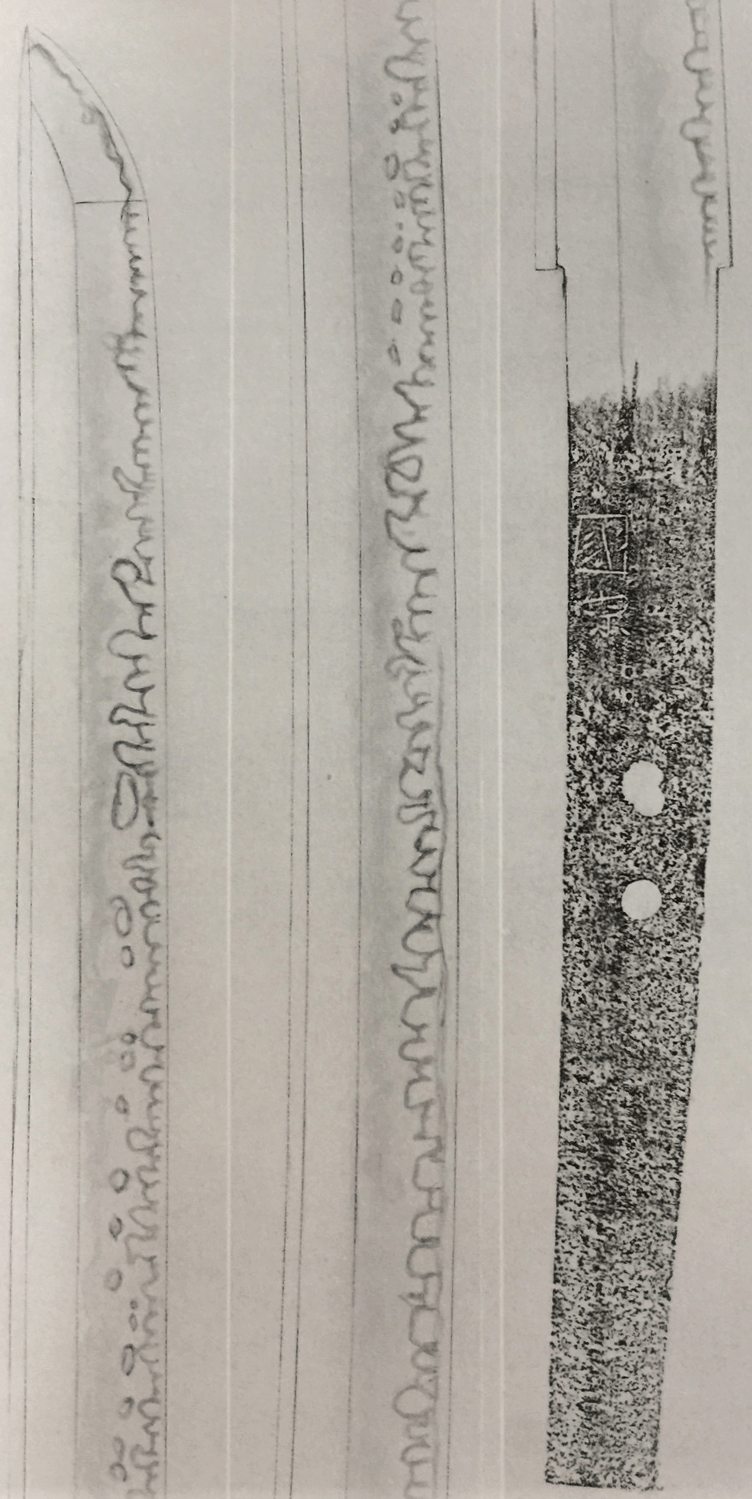

Characteristics: Munei (shortened and without signature). Yamato-den, Tegai-ha (Yamato school Tegai group). Length is two shaku, two sun, eight &1/2 bu (27 1/4 inches), small kissaki and funbari. Hamon: Niju-ba, Sunagashi. Boshi: Yakizume. Ji-hada: Itame with masame, Nie-hon’i .

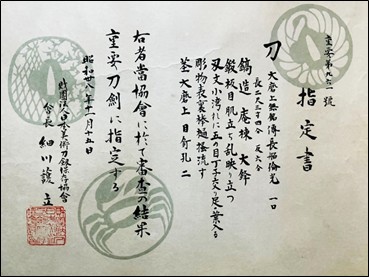

The full view of the sword and Kantei-sho (NBTHK Certification). “Tokubetsu Hozon Token”.

My sword: acquired at Dai Token Ichi (大刀剣市)Bizen Osafune Tomomitsu (備前長船倫光) Length: 2 feet 4 inches, Shape: Shinogi zukuri, Hada:itame midare-utsuri, Hamon: konotare gunome choji

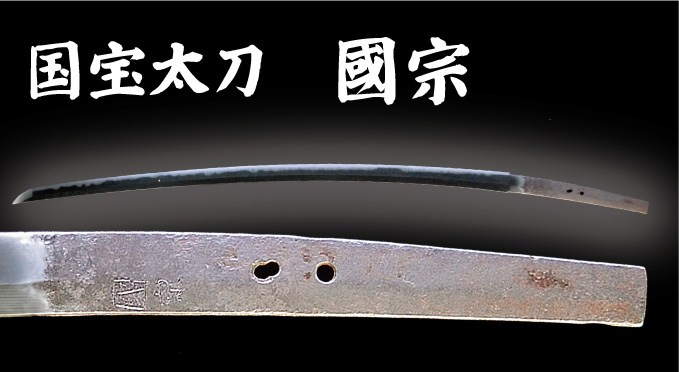

Bizen Saburo Kunimune (備前三郎国宗) Photo from “Nippon-to Art Sword of Japan, ” The Walter A. Compton Collection. National Treasure

Bizen Saburo Kunimune (備前三郎国宗) Photo from “Nippon-to Art Sword of Japan, ” The Walter A. Compton Collection. National Treasure The above photo is from the official website of the Terukuni Jinja Shrine in Kyushu.

The above photo is from the official website of the Terukuni Jinja Shrine in Kyushu.

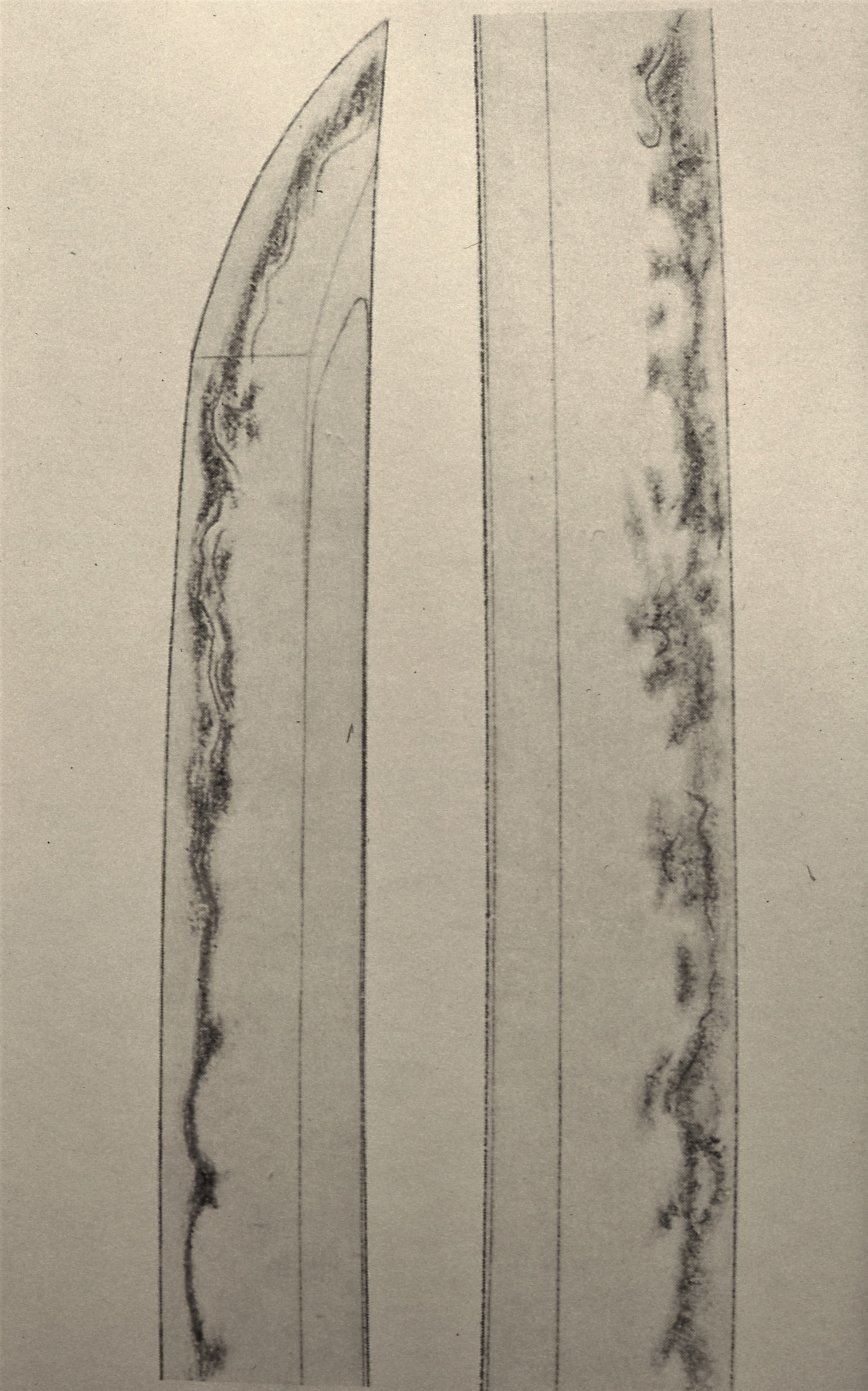

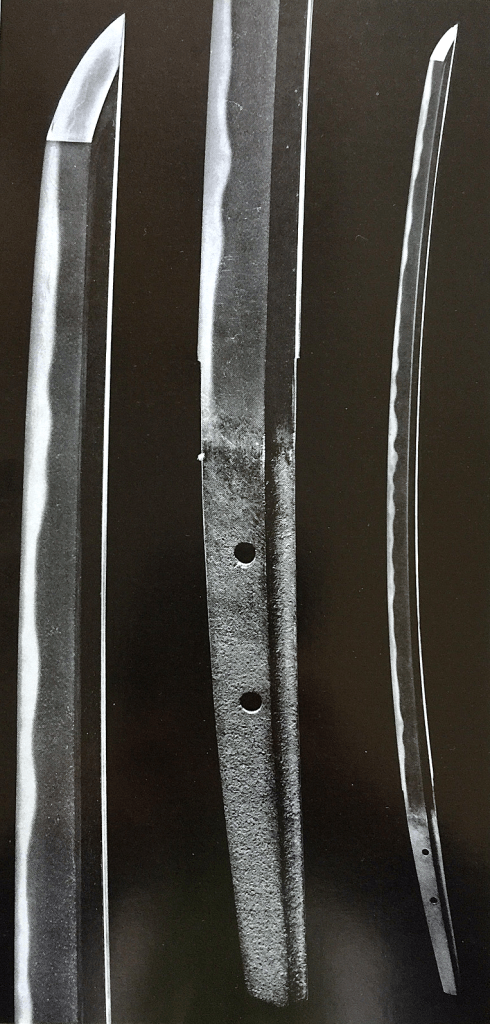

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Masamune from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

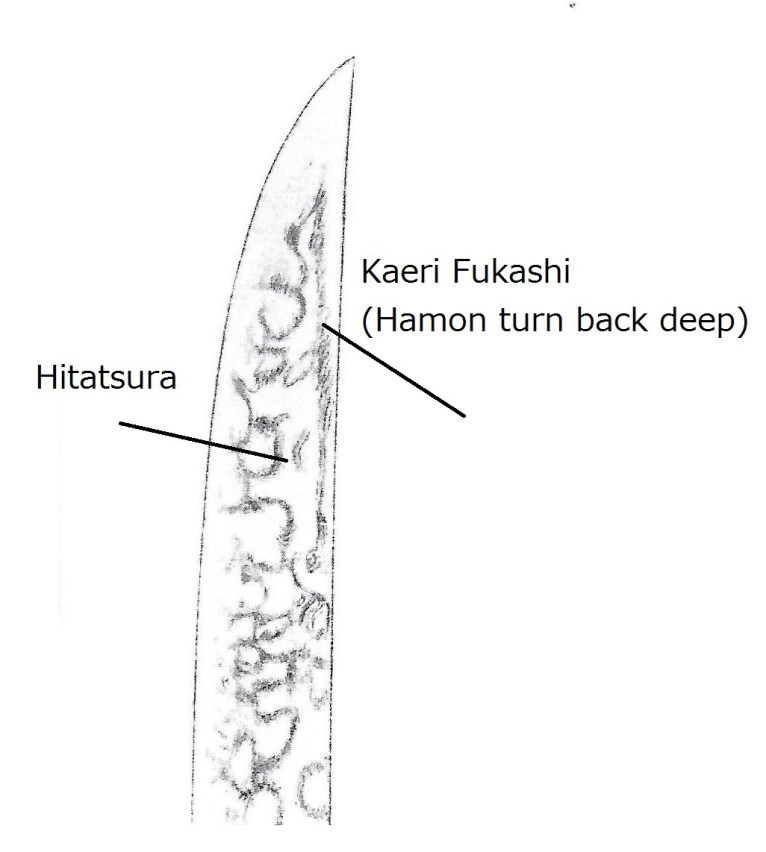

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)

Hiromitsu from Sano Museum Catalog (permission granted)