This chapter is a detailed part of Chapter 5, Heian Period Sword. Please read Chapter 5 before this section. More sword terminology will be used in the upcoming chapters. These terms were explained in Chapters 1-31. If you encounter unfamiliar sword terms, please refer to Chapters 1 through 31.

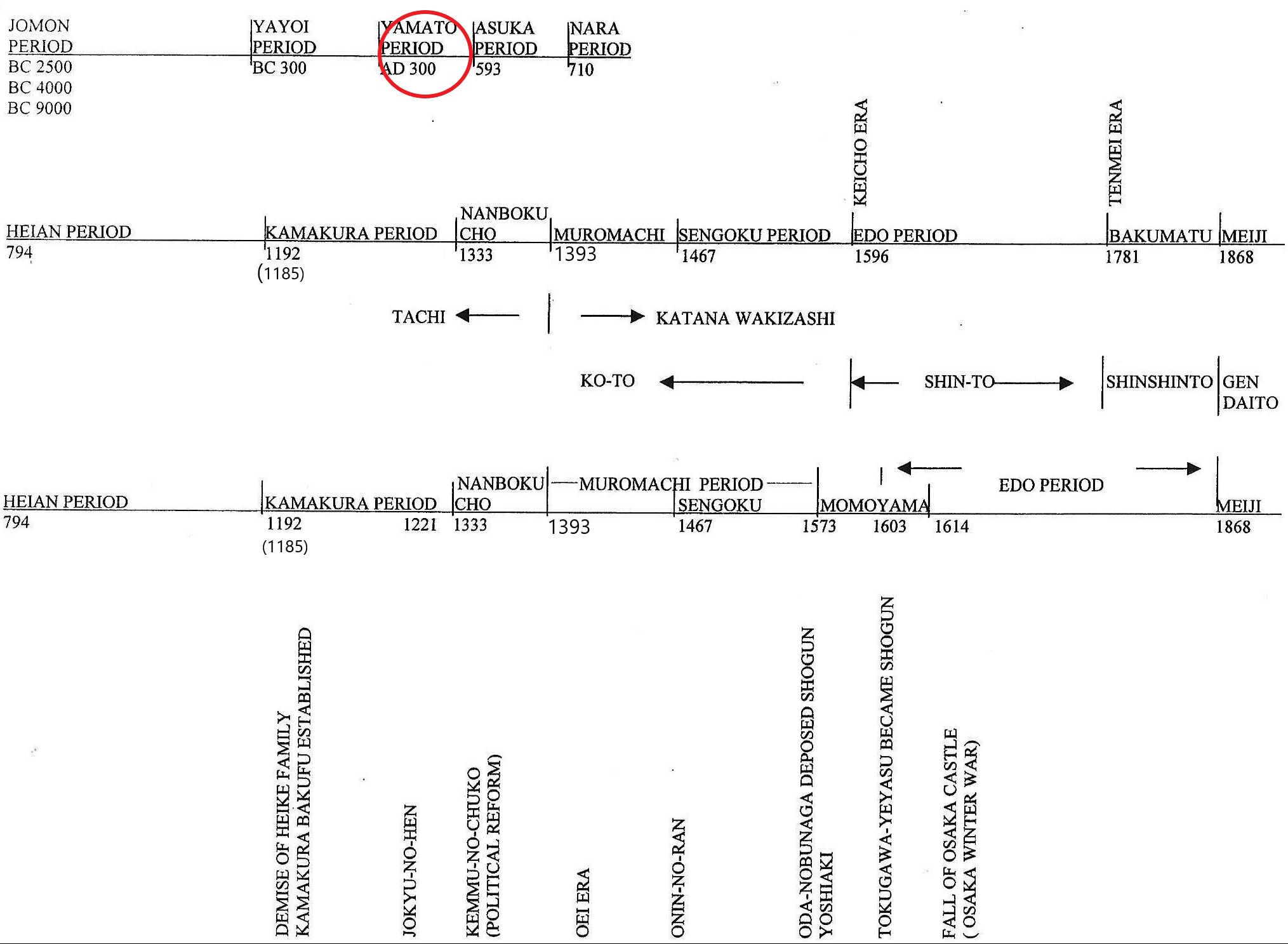

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this sect

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this sect

During the Heian period, several swordsmith schools were active. We use the word “den” to refer to these schools. These include Yamashiro-den (山城伝), Yamato-den (大和伝), and Bizen-den (備前伝). Additionally, the following regions had other active groups during the Heian period: Hoki-no-kuni (伯耆の国) and Oo-u (奥羽). Oo-u is pronounced “Oh,” and “U” as in uber.

Yamashiro Den (山城伝 )

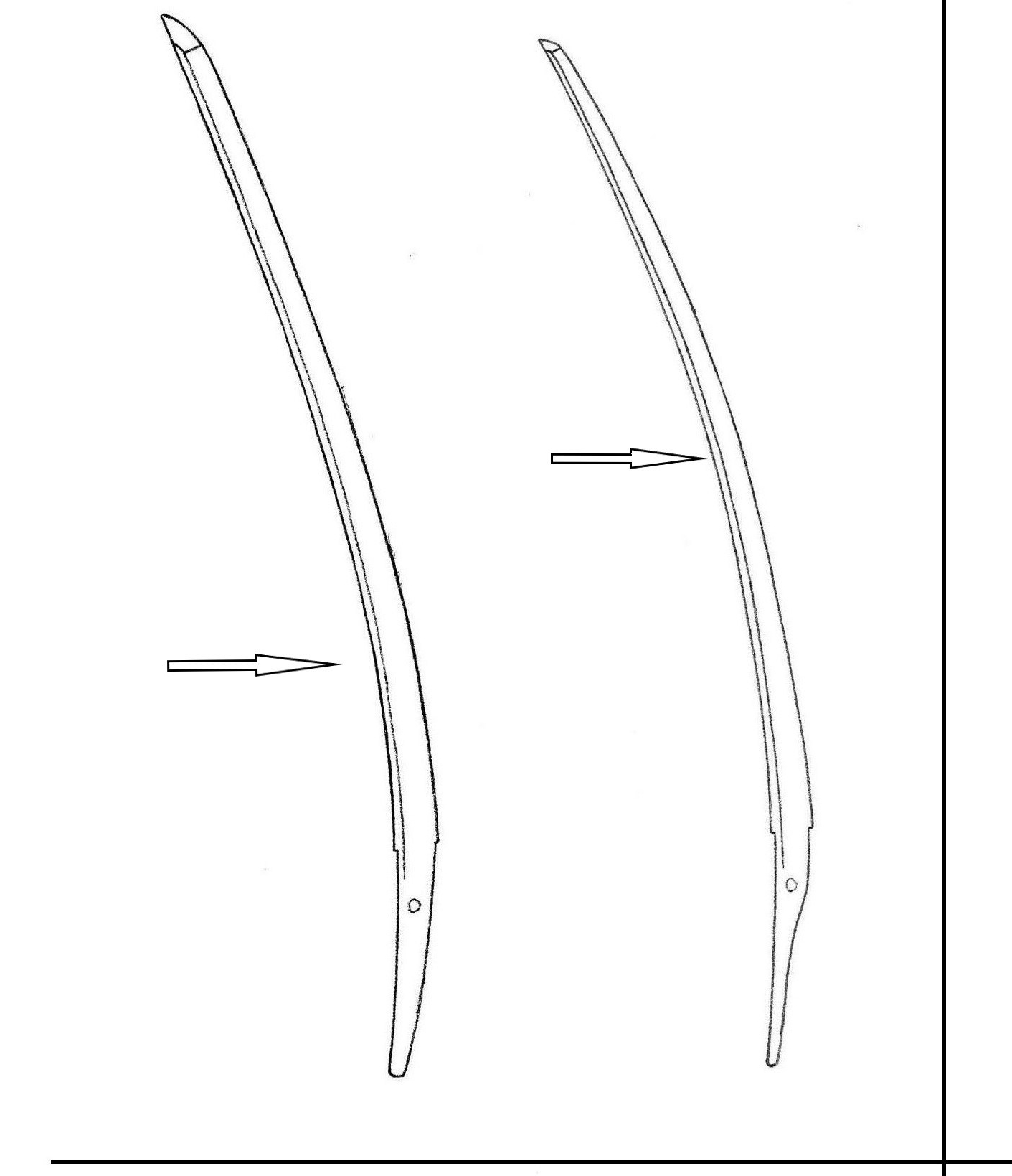

During the Heian period, among Yamashiro-den swords, the most famous sword was the “Mikazuki Munechika“ (三日月宗近) by Sanjo Munechika (三条宗近). Mikazuki means crescent. It was named Mikazuki Munechika because the crescent-shaped uchinoke (collection of Nie) pattern appears in the hamon. It has a graceful shape, a narrow body, koshi-zori, funbari, and a small kissaki. The sword shows a wood grain pattern on its surface, with suguha with nie mixed with small irregular lines, and sometimes a nijyu-ha (double hamon: 二重刃) appears. Sanjo Munechika lived in the Sanjo area of Kyoto. His sword style was passed down through his sons and grandsons: Sanjo Yoshiie (三条吉家), Gojo Kanenaga (五条兼永), and Gojo Kuninaga (五条国永). Gojo is also a district in Kyoto

三日月宗近 Mikazuki Munechika 東京国立博物館蔵 Tokyo National Museum Photo from “Showa Dai Mei-to Zufu 昭和大名刀図譜” published by NBTHK

Houki -no-Kuni (伯耆の国)

Houki-no-kuni is the area now called Tottori Prefecture. It is known for producing high-quality iron. The sword, “Doujigiri Yasutsuna” (童子切安綱), made by Hoki-no-yasutsuna (伯耆の安綱), was one of the most famous swords of its time.

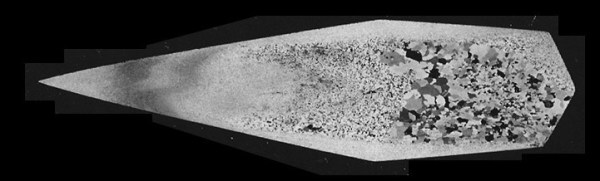

The characteristics of Yasutsuna’s sword ——- It has a graceful shape with a small kissaki, a narrow hamon (often suguha with ko-choji), coarse nie in the hamon area, and a large wood grain pattern mixed with masame on the ji-hada. The hamon area often shows inazuma and kinsuji. The boshi area is yakizume, and the kaen (pronounced ka as in calf, en as in engineer) has a slight turn back.

伯耆の安綱 (Hoki no Yasutsuna) 佐野美術館図録 (Sano Musem Catalogue) Permission to use granted

Bizen Den (備前伝 )

Bizen is in Okayama Prefecture today. It is known for producing high-quality iron. From the Heian period to the present, Bizen has been famous for its sword-making tradition. The sword-making group in this area during the Heian period was called the Ko-bizen group. The most famous swordsmiths in the Ko-bizen group included Bizen Tomonari (備前友成), Bizen Masatsune (備前正恒), and Bizen Kanehira (備前包平).

Ko-bizen group’s characteristics ———- A graceful, narrow body, a small kissaki, and a narrow-tempered line with ko-choji (small irregular) with inazuma and kin-suji. The ji-hada displays a small wood-grain pattern.

Bizen Kanehira (備前包平) Sano Museum Catalogue (佐野美術館図録) (Permission to use granted)

I saw Ko-bizen Sanetsune (真恒) at Mori Sensei’s house. That was one of the kantei-to of that day. I received a dozen*ᴵ. The book written by Hon’ami Koson was used as our textbook. Each time I saw a sword at Mori Sensei’s house, I recorded the date next to the swordsmith’s name in the book we used. It was Nov. 22, 1970. It had a narrow body line, a small kissaki (Ko-bizen komaru), kamasu*2 (no fukura), and suguha. Kamasu is a condition in which the fukura (arc) is much less than usual. Looking back, it is amazing that we had the opportunity to study such famous swords as our study materials.

Kantei-Kai

Kantei-kai is a study meeting. Usually, several swords are displayed, with the nakago area covered. Attendees try to guess the sword maker’s name and submit their answer sheets to the judge. Below are the grades.

Atari —– If your answer is the exact correct name, you get Atari. That is the best answer.

Dozen —— The second best is a dozen. It means nearly a correct answer. The subject sword was made by the family or clan of the right den. A dozen is considered very good. It indicates that the student has solid knowledge of the particular group.

Kaido Yoshi —– This means it is correct regarding the line, but not about the family.

Jidai Yoshi — it means the time or period is correct. Each Kantei-kai has its own grading system. Some may not have a “Jidai Yoshi” grade.

Hazure——– the wrong answer.

Once all answer sheets are submitted, they are graded and returned. The judge reveals the correct answer and explains why.

*1 Dozen: Almost the same as the correct answer. *2 Kamasu: A name of a fish that has a narrow, pointed head.

Part of the Burke Album, a property of Mary Griggs Burke (Public Domain). Paintings by Mitsukuni (土佐光国), 17th century. The scenes are based on “The Tales of Genji.“

Part of the Burke Album, a property of Mary Griggs Burke (Public Domain). Paintings by Mitsukuni (土佐光国), 17th century. The scenes are based on “The Tales of Genji.“