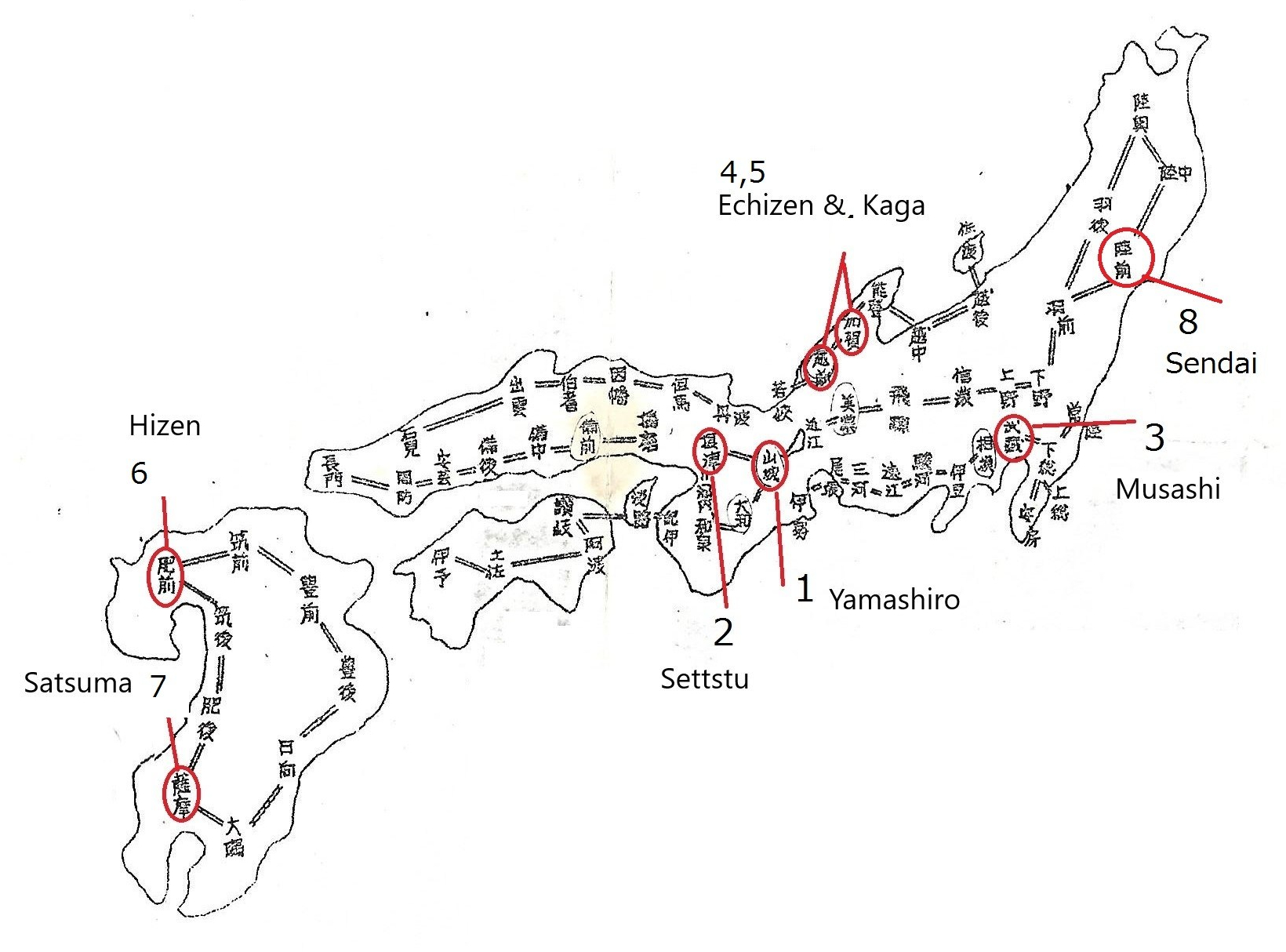

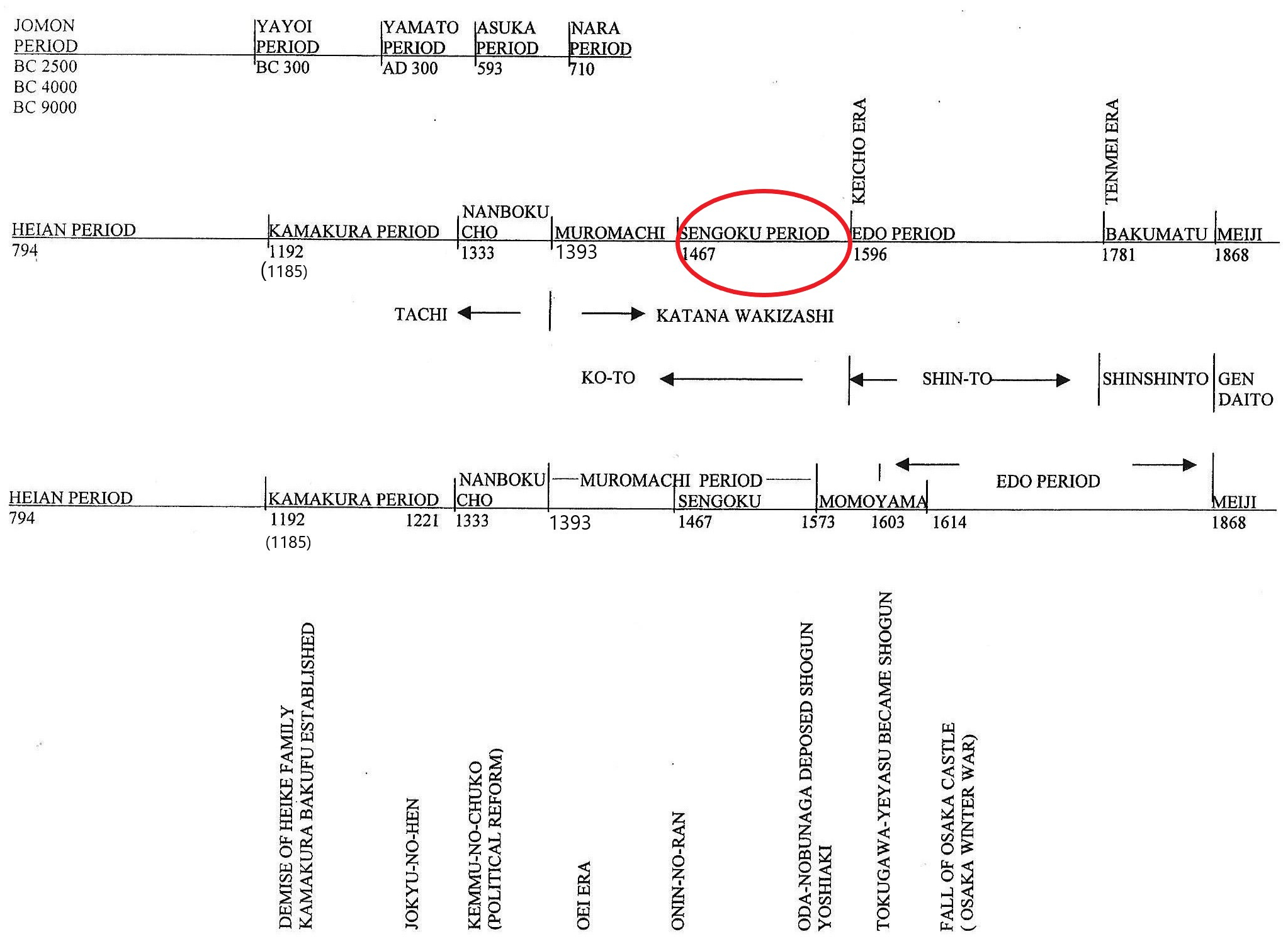

The red circle above indicate the time we discuss in this chapter

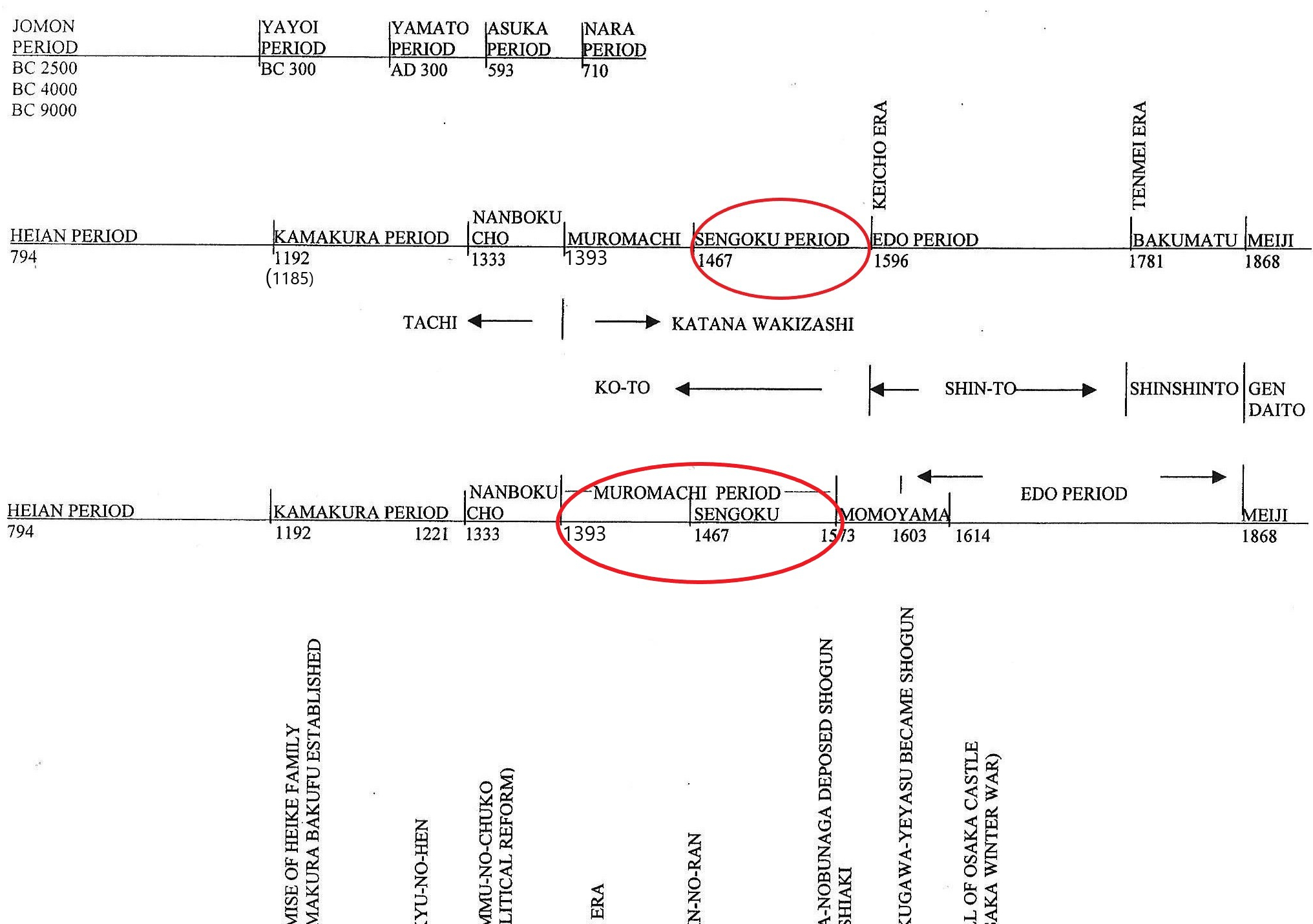

The Bakumatsu period is the last part of the Edo period in sword history. See the circle on the middle timeline above. However, political history does not divide the Edo and Bakumatsu periods, and there is no specific date that separates them.

The Azuchi-Momoyama period (安土桃山) falls between when Oda Nobunaga (織田信長) deposed Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki (将軍足利義昭) in 1573 until Tokugawa Iyeyasu became shogun in 1603, or when Tokugawa Iyeyasu defeated Toyotomi Hideyori (Hideyoshi’s son) during the Osaka Winter Campaign in 1615. The Azuchi-Momoyama period was a brief era during which Oda Nobunaga (織田信長), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉), and Tokugawa Iyeyasu (徳川家康) engaged in intricate political struggles. During this period, Japan experienced significant cultural and economic growth. After a long period of war, the country was finally reunited and entered a peaceful period.

The stories of Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Iyeyasu are the most popular among the Japanese. These stories are often shown on TV programs and movies. The Tokugawa family ruled Japan during the Edo period.

The Tokugawa government was called the Tokugawa Bakufu. Throughout the Edo period, the Tokugawa family’s direct descendants, usually the firstborn sons, became the shoguns. However, the emperors co-existed at the same time. Even though they did not hold political power, the imperial family still maintained imperial status.

The Edo period was peaceful. Unlike previous periods, there were no wars. Yet, later in the period, the long-lasting Edo period (which lasted about 260 years) became stagnant and began to show structural and financial problems in its rule. This is the Bakumatsu (幕末) time, the final phase of the Edo bakufu

In the previous chapter, Chapter 25, Edo Period History explained that the Edo bakufu closed the country to the outside world for most of that era. The only place in Japan with access to foreign countries was Dejima in Nagasaki (the southern part of Japan). During the Bakumatsu period, several European ships visited Japan, asking (more like demanding) that Japan open its ports to provide water and other supplies for whaling ships. Also, some countries sought to trade with Japan. Those countries were England, Russia, America, and others.

In 1792, the Russian government sent an official messenger to Japan, demanding that Japan open its ports to trade. In 1853, Commodore Perry from the U.S. arrived with four massive warships at the port of Uraga (浦賀: now in Kanagawa Prefecture) and demanded that Japan open its ports to water, fuel, and other supplies for U.S. whaling ships.

At the end of the Bakumatsu period, the Tokugawa bakufu faced political and financial difficulties in governing the country. Also, intellectuals feared that Japan might face trouble, similar to that China faced during the Opium War (1839-1842) with England. Pressures to open the country were building up. It became evident that Japan could no longer keep the country closed. At that time, Commodore Perry arrived at Uraga with four massive black warships and demanded that Japan open its ports. These warships scared the Japanese and fueled the wave of anti-bakufu sentiment. The Meiji Revolution was ready to happen, and Perry’s warships were the final push.

The Tokugawa bakufu signed treaties with several foreign countries and opened a few ports for trade. The bakufu’s authority weakened, and Japan was divided into several political groups. While they fought chaotically, the Meiji Restoration movement continued. In 1868, the Tokugawa bakufu vacated Edo Castle in Edo (now Tokyo), and the Meiji Emperor moved in. The Meiji Shin Seifu (Meiji’s new government) was formed, centered around the Meiji Emperor, and the Tokugawa bakufu came to an end.

File:Commodore-Perry-Visit-Kanagawa-1854.jpg From ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/黒船 Public Domain

File:Commodore-Perry-Visit-Kanagawa-1854.jpg From ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/黒船 Public Domain

Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s visit of Kanagawa, near the site of present-day Yokohama on March 8, 1854. Lithography. New York: E. Brown, Jr.