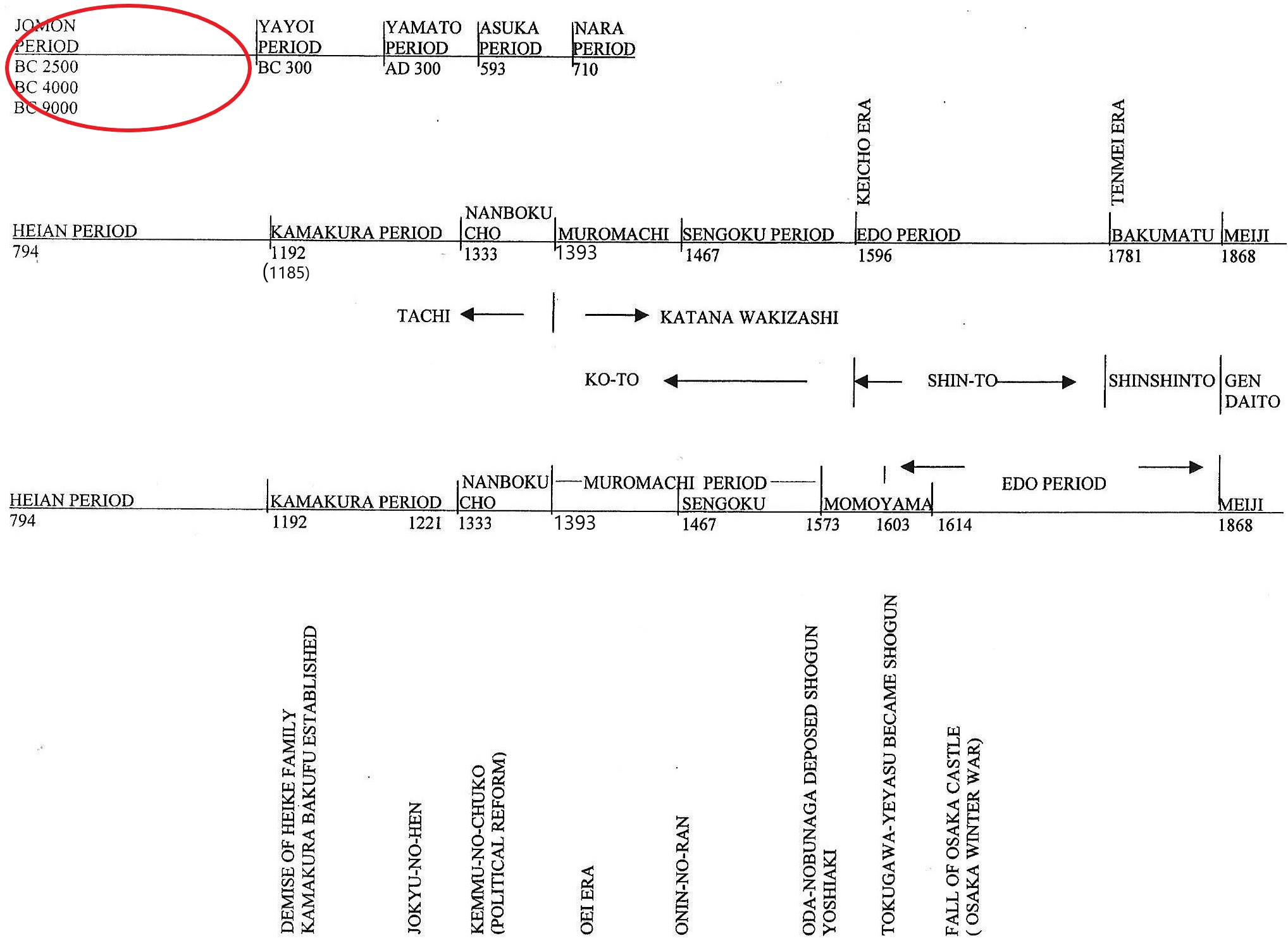

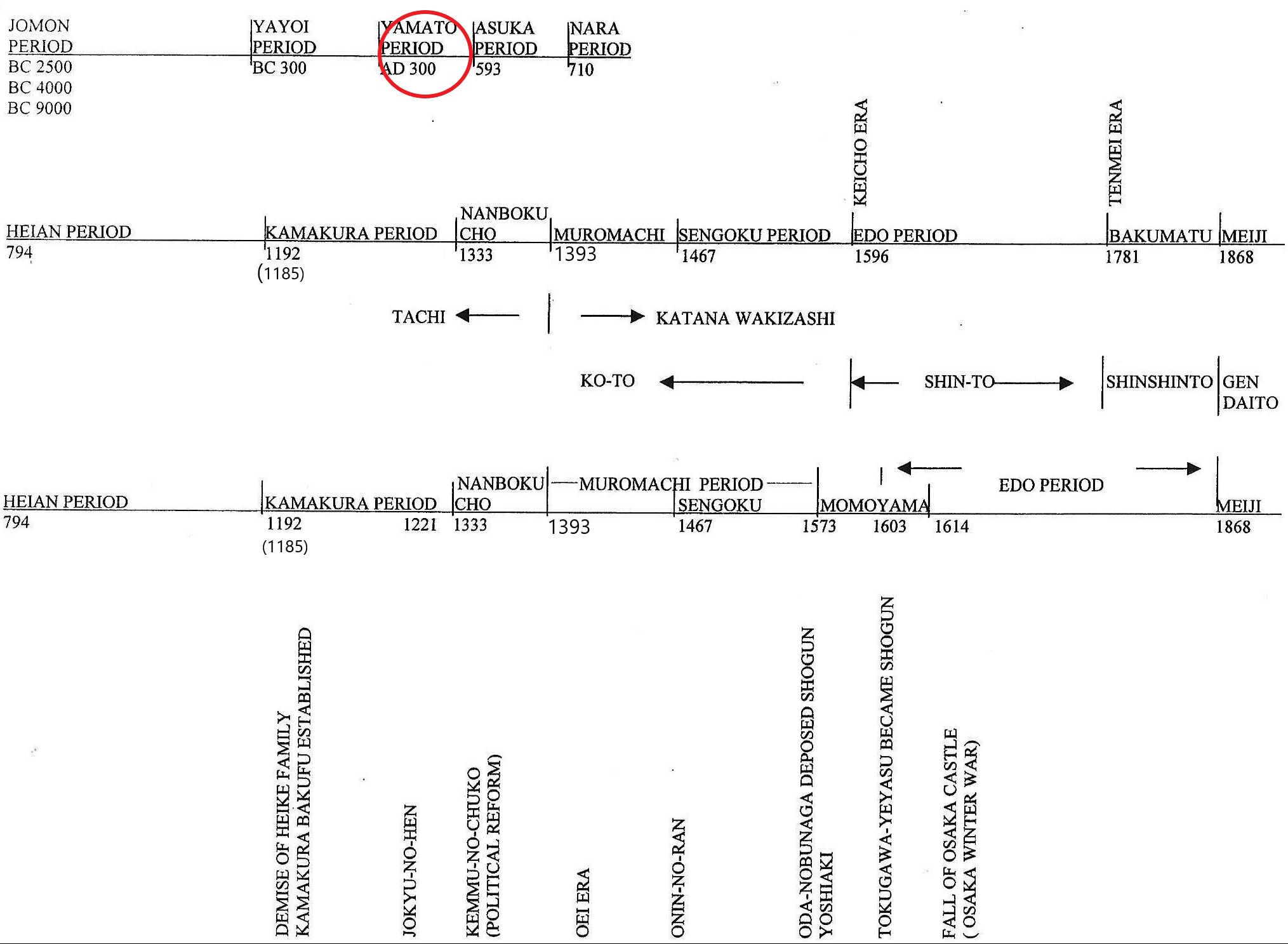

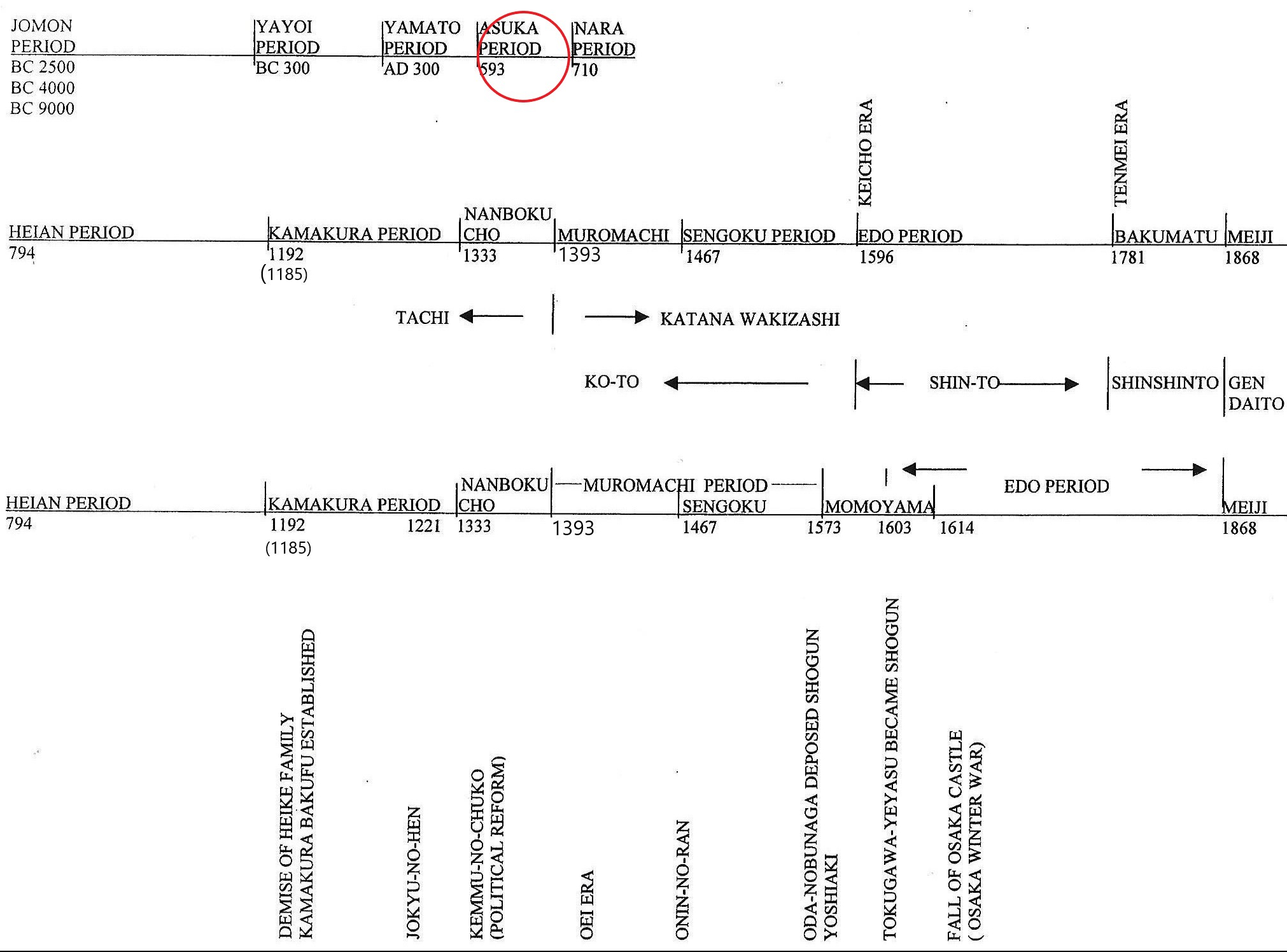

The circle indicates the time we discuss in this section

Many swordsmiths worked in the Bizen (備前) school during the early Kamakura period. However, their sword style is generally somewhat similar to the Yamashiro style. Therefore, they are called Ko-bizen (古備前), meaning old Bizen.

The true Bizen school style appeared during the Middle Kamakura period. Bizen Province had many advantages for producing great swords. The area produced high-quality iron and abundant firewood. Also, its location was conveniently located for people to travel from different regions. As a result, many swordsmiths gathered there and produced large quantities of swords. Due to competition among these smiths, the quality of Bizen swords is generally higher than that of other schools. Therefore, it is often difficult to appraise Bizen swords because of the many subtle differences among the different swordsmiths.

The following three features are the most distinctive characteristics of the Bizen school.

1. Nioi-base tempered line. The Nioi-base tempered line has finer dots than the Nie-base. These dots are so small that they almost appear as a line. Technically, the tempering processes of these two are identical. See the illustration below. 2. Ji-hada (surface of the body) appears soft. 3. Reflection (utsuri) appears on the surface.

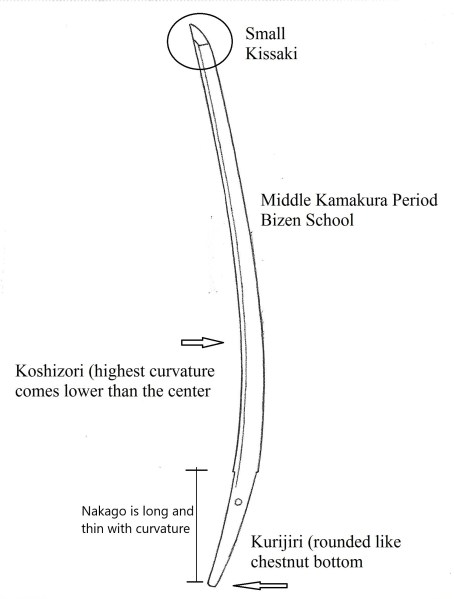

Sugata (shape) —The length is approximately 33 inches ± a few inches. The blade is slightly wide and appears sturdy. The curvature of the blade is koshizori (腰反), meaning the deepest curve is at the lower part. The body has an average thickness, and the kissaki is small.

Horimono (engraving) ——Engravings are rare. The tip of the hi extends all the way to ko-shinogi, filling the entire area.

Nakago ——– Long and thin with a curve. The end of the nakago is rounded and resembles the bottom of a chestnut (kuri). This shape is called kurijiri. Refer to the illustration of the sword above.

Hamon (tempered area pattern)—— Nioi base. The tempered area is wide and consistent width. The size of the midare (irregular wavy tempered pattern) is uniform.

Boshi ——– The same tempered pattern continues upward to the boshi area, and it often shows choji- midare (clove-shaped wavy pattern) or yakizume.

Ji-hada ———— Fine and well forged. The steel appears soft. On the steel surface, small and large wood-grain patterns are mixed. Chikei (condensation of nie) and utsuri (cloud-like reflection) appear.

Bizen School Sword Smiths during Middle Kamakura Period

- Fukuoka Ichimonji (福岡一文字) group ————-Norimune (則宗) Sukemune (助宗)

- Yoshioka Ichimonji (吉岡一文字) group ——–Sukeyoshi (助吉) Sukemitsu (助光)

- Sho-chu Ichimonji (正中一文字) group —————Yoshiuji (吉氏) Yoshimori (吉守)

- Osafune (長船) group ———–Mitsutada (光忠) Nagamitsu (長光) Kagemitsu (景光)

- Hatakeda(畠田) group ————————————-Moriie (守家) Sanemori (真守)

- Ugai (鵜飼) group ————————————————- Unsho (雲生) Unji (雲次)

Fukuoka Ichimonji (一文字) from “Nippon-to Art Swords of Japan” The Walter A. Compton Collection

![7 Taira_no_Kiyomori,TenshiSekkanMiei[1]](https://studyingjapaneseswords.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/7-taira_no_kiyomoritenshisekkanmiei1-e1576620323401.jpg?w=538)

Hilt of a Japanese straight sword. Circa 600 AD. From Wikipedia Commons, the free media repository

Hilt of a Japanese straight sword. Circa 600 AD. From Wikipedia Commons, the free media repository

The photo is from Creative Commons, a free media source for online pictures

The photo is from Creative Commons, a free media source for online pictures