Finally, the revised ”Study of Japanese Swords” is on Amazon. Please visit Amazon for both softcover and hardcover.

Finally, the revised ”Study of Japanese Swords” is on Amazon. Please visit Amazon for both softcover and hardcover.

By clicking below, it will take you to that chapter directly. Part 2 is a detailed part of the corresponding chapter.

4 | Heian Period History 794 – 1192 (平安時代)

5 | Heian Period Swords (平安時代太刀)

6 | Kamakura Period History 1192 – 1333 (鎌倉時代歴史)

7 | Overview of the Kamakura Period Swords (鎌倉時代太刀概要)

8 | Middle Kamakura Period : Yamashiro Den (鎌倉中期山城伝)

9 | Middle Kamakura Period : Bizen Den (鎌倉中期備前伝)

10 | Jokyu-no-ran 1221(承久の乱)

12 | Middle Kamakura Period:Tanto (鎌倉中短刀)

13 | Late Kamakura Period : Genko (鎌倉末元寇)

14 | Late Kamakura Period Sword (鎌倉末太刀)

15 | The Revival of Yamato Den(大和伝復活)

16 | Late Kamakura period: Soshu Den Tanto (相州伝短刀)

17 | Nanboku-cho Period History 1333-1392 (南北朝歴史)

18 | Nanboku-cho Period Sword:North and South dynasty (南北朝太刀)

19 | Nanboku-Cho Tanto (南北朝短刀)

20 | Muromachi Period History (室町時代歴史)

21 | Muromachi Period Sword (室町時代刀)

22 | Sengoku Period History (戦国時代)

23 | Sengoku Period Sword (戦国時代刀)

24 | Sengoku Period Tanto (戦国時代短刀)

25 | Edo Period History 1603 – 1867 (江戸時代歴史)

26 | Over view of Shin-to (新刀) — Ko-to & Shin-to Difference

27 | Shinto Sword — Main Seven Regions (Part A : 主要7刀匠地)

28 | Shinto Sword — Main Seven Regions (part B : 主要7刀匠地)

29 | Bakumatsu Period History 1781 – 1868 (幕末歴史)

30 | Shin-Shin-To 1781-1867 (Bakumatsu Period Sword 新々刀)

32 | Japanese swords after WWII

33 | Information on Today’s Swordsmiths

35 | Part 2 of — 2 Joko-To (上古刀)

36 | Part 2 of — 3 Names of the Parts

37 | Part 2of — 4 Heian Period History 794-1192 (平安時代)

38 | Part 2 of — 5 Heian Period Sword 794-1192 (平安時代太刀)

39 | Part 2 of — 6 Kamakura Period History 192 – 1333 (鎌倉時代歴史)

40 | Part 2 of — 7 Overview of Kamakura Period Sword (鎌倉太刀概要)

41 | Part 2 of — 8 Middle Kamakura Period : Yamashiro Den (鎌倉中期山城伝)

42 | Part 2 of — 9 Middle Kamakura Period : Bizen Den (鎌倉中期備前伝)

43 | Part 2 of — 10 Jyokyu-no-Ran and Gotoba-joko (承久の乱)

44 | Part 2 of — 11 Ikubi Kissaki(猪首切先)

45 | Part 2 of — 11 Ikubi Kissaki (continued from Chapter 44)

46 | Part 2 of — 12|Middle Kamakura Period : Tanto 鎌倉中期短刀

47 | Part 2 of — 13 Late Kamakura Period : Genko (鎌倉末元寇)

48 | Part 2 of — 14|Late Kamakura Period Sword : Early Soshu Den (鎌倉末刀)

49 | Part 2 of — 15 The Revival of Yamato Den (大和伝復活)

50 | Part 2 of — 16 Late Kamakura Period: Tanto (Early Soshu-Den 鎌倉末短刀, 正宗墓)

51 | Part 2 of — 17 Nanboku-Cho Period History 1333 – 1392 (南北朝歴史)

52 | Part 2 of — 18 Nanboku-Cho Period Swords (南北朝太刀)

53 | Part 2 of — 19 Nanboku-Cho Tanto (南北朝短刀)

54 | Part 2 of — 20|Muromachi Period History (室町歴史)

55 | Part 2 of — 21 Muromachi Period Sword (室町時代刀)

56 | Part 2 of — 22 Sengoku Period History (戦国時代歴史)

57 | Part 2 of — 23 Sengoku Period Sword (戦国時代刀)

58 | Part 2 of — 24 Sengoku Period Tanto (戦国時代短刀)

59 | Part 2 of — 25 Edo Period History 1603 – 1867 (江戸時代歴史 )

60 | Part 2 of — 26 Overview of Shin-To (新刀概要)

61 | Part 2 of — 27 Shin-to Main 7 Regions (part A)

62 | Part 2 of — 28 Shin-To Main 7 Region (part B)

63 | Part 2 of — 29 Bakumatsu Period History (幕末時代)

64 | Part 2 of — 30 Shin-Shin-To : Bakumatsu sword (新々刀 )

65 | The Sword Observation Process

This Chapter is a detailed Chapter of the 30|Bakumatsu Period, Shin Shin-to. Please read Chapter 30 before reading this chapter.

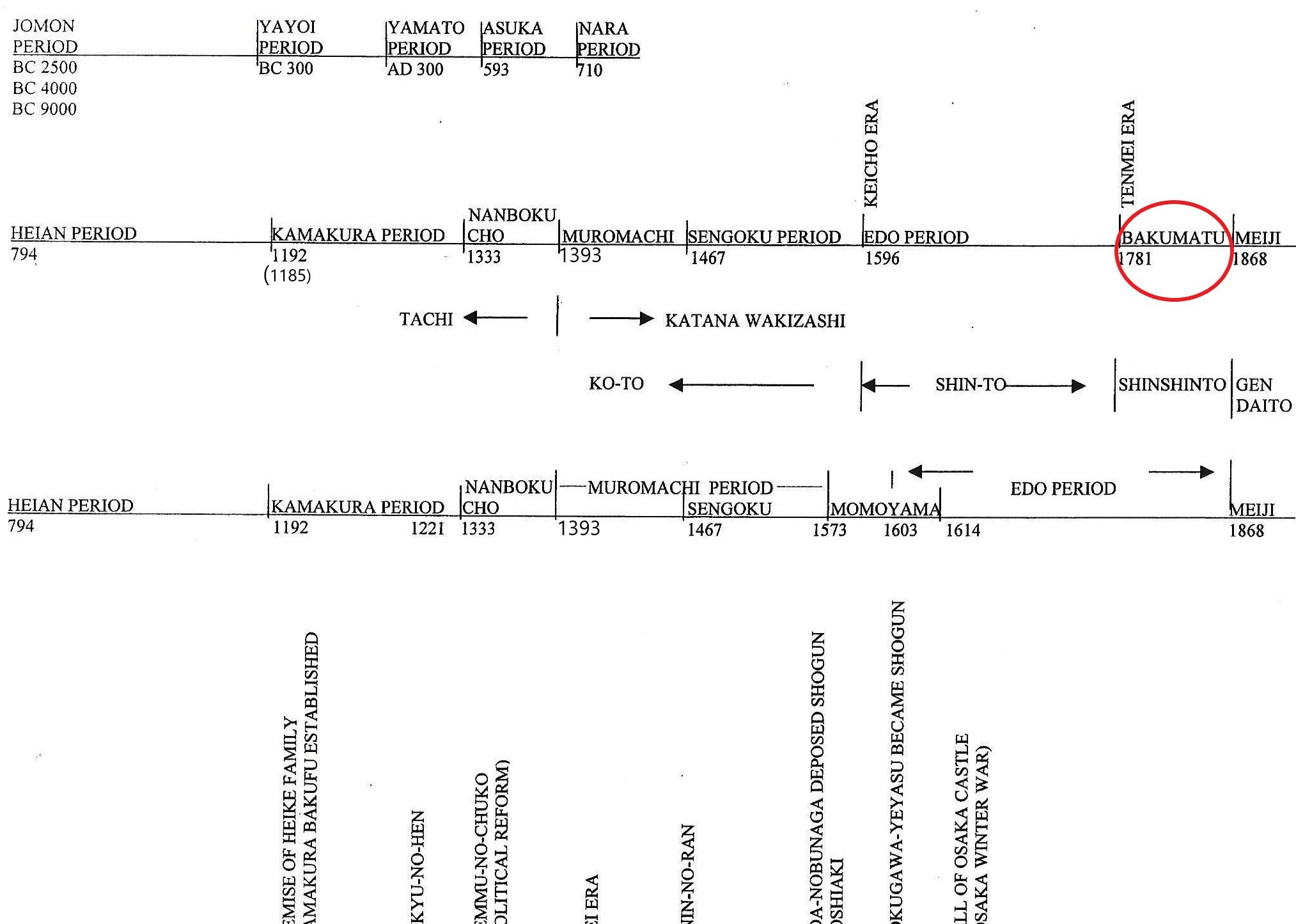

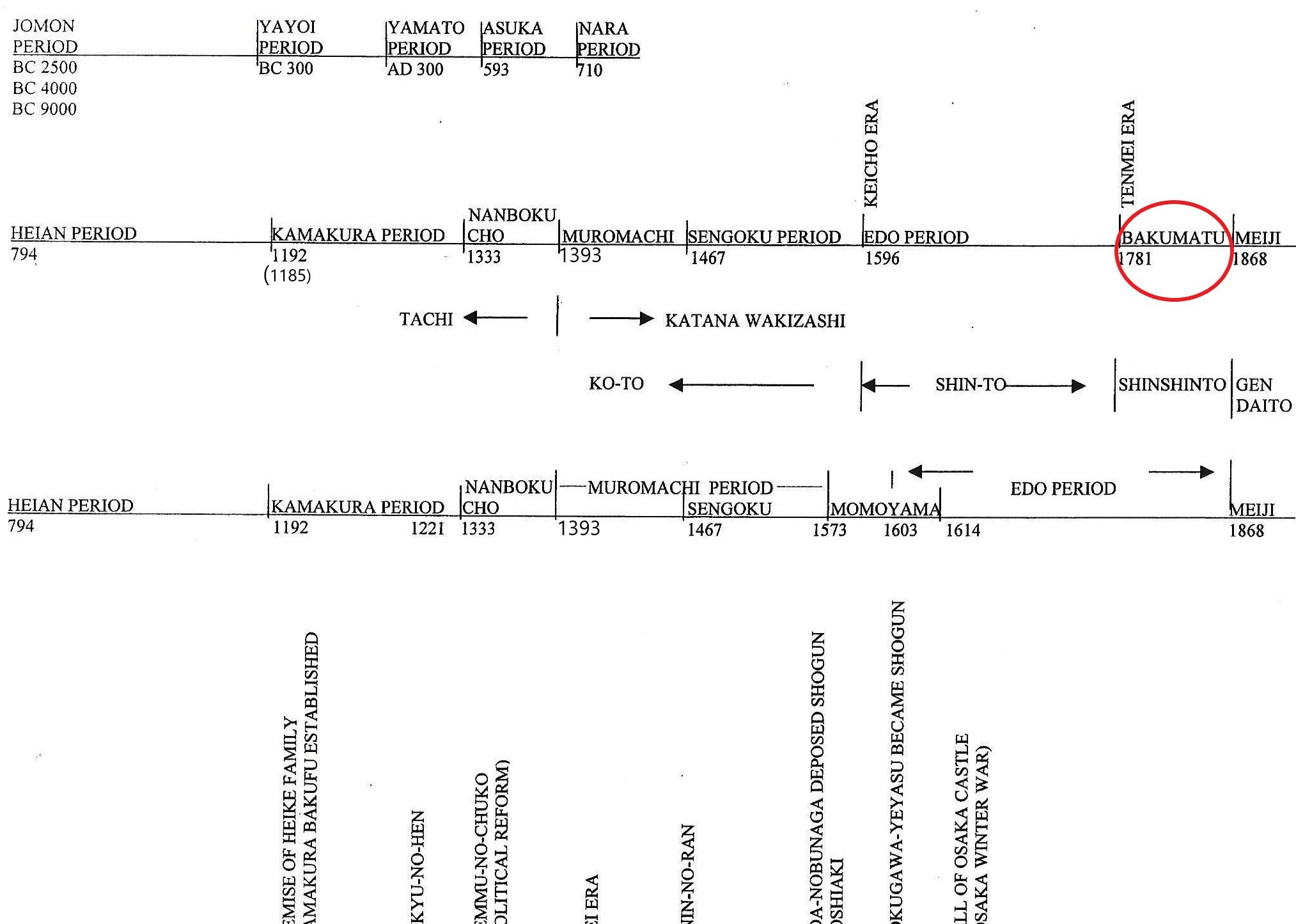

Swords made between the Tennmei era (天明 1781) and the end of the Keio era (慶應) are called shin shin-to. Please refer to the timeline above. This period was when Japan was moving toward the Meiji Restoration, known as the Bakumatsu era. During this time, sword-making became active again. Below are the well-known swordsmiths from the main areas.

Musashi no Kuni (武蔵の国: Tokyo today)

Suishinshi Masahide (水心子正秀) ——— When Suishinshi Masahide made Yamashiro-den style swords, their shapes resembled those of ko-to period swords; funbari, an elegant shape; chu-suguha (medium straight); komaru-boshi, with fine wood grain. When he forged in the Bizen style, he made a Koshi-zori shape, similar to a ko-to made by Bizen Osafune. Nioi with ko-choji, and katai-ha (refer to 30| Bakumatsu Period Sword 新々刀). In my old sword textbook, I noted that I saw Suishinshi in November 1970 and October 1971.

Taikei Naotane (大慶直胤) ————————–Although Taikei Naotane was part of the Suishinshi group, he was one of the top swordsmiths. He had an exceptional ability to forge a wide range of sword styles beautifully. When he made a Bizen-den style, it resembled Nagamitsu from the Ko-to era, with nioi. Also, he did sakasa-choji as Katayama Ichimonji had done. Katai-ha appears. The notes in my old textbook indicate I saw Naotane in August 1971.

Minamoto no Kiyomaro (源清麿) ————————– Kiyomaro wanted to join the Meiji Restoration movement as a samurai; however, his guardian recognized Kiyomaro’s talent as a master swordsmith and helped him become one. It is said that because Kiyomaro had a drinking problem, he was not very eager to make swords. At age 42, he committed seppuku. Kiyomaro, who lived in Yotsuya (now part of Shinjuku, Tokyo), was called Yotsuya Masamune because he was as good as Masamune. His swords featured wide-width, shallow sori, stretched kissaki, and fukura-kereru. The boshi is komaru-boshi. Fine wood grain ji-gane.

Settsu no Kuni ( 摂津の国: Osaka today)

Gassan Sadakazu (月山貞一) ———- Gassan excelled in the Soshu-den and Bizen-den styles, but he was capable of making in any style. He was as much a genius as Taikei Naotane. You must pay close attention to notice a sword made by Gassan from genuine ko-to. He also had remarkable carving skills. His hirazukuri-kowakizashi, forged in the Soshu-den style, looks just like a Masamune or a Yukimitsu. He forged in the Yamashiro-den style, with Takenoko-zori, hoso-suguha, or chu-suguha in nie. Additionally, he forged the Yamato-den style with masame-hada.

This chapter is a detailed part of Chapter 29, Bakumatu Period History. Please read Chapter 29 before reading this chapter.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The final period of the Edo period, roughly the Tenmei era (天明), from 1781 to 1868, is known as the Bakumatsu. During this period, Japan’s economy started to stagnate.

Several Tokugawa shoguns across generations attempted to implement financial reforms, each with some success, but none resolved the core economic problems.

The Tokugawa Bakufu mainly tried to impose fiscal restraint on the government, forcing people to lead frugal lives and even banning small luxuries. This only shrinks the economy and worsens the situation. Additionally, they raised the prevailing interest rate, believing it might resolve the problem. It was a typical non-economist solution. The interest rate should be lowered in situations like this. As a result, lower-level samurai became more impoverished, and farmers often revolted. Additionally, many natural disasters affected agricultural areas. The famous Kurosawa movie “Seven Samurai” was set around this time. As we all know, “Magnificent Seven” is a Hollywood version of “Seven Samurai.”

Gradually, a small cottage industry emerged alongside increased farming productivity, led by local leaders. Merchants became wealthier, and city residents grew richer. However, the gap between the rich and the poor widened. The problem of ronin (unemployed samurai) has become serious and almost dangerous to society.

The Edo Towns-people’s Culture

During this time, novels were also written for everyday people, not just for the upper class. In the past, paintings were associated with religion and were only accessible to the upper class. Now, they are for the general public.

The Bakumatsu period was a golden age for “ukiyo-e (浮世絵).” Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿1753-1800) was well-known for his portraits of women. Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎1760-1849) and Ando Hiroshige (安藤広重1797-1858) were famous for their landscape woodblock prints. Maruyama Okyo (円山応挙) painted using European perspective techniques. Katsushika Hokusai’s daughter also drew some of her paintings with perspective. Her name is “Ooi, 応為. ” Only a few of her works remain today. It is said that even her genius father was surprised by her drawing ability.

Although the number was small, some people learned Dutch. The Netherlands was one of only two countries allowed to enter Japan. These individuals translated a European medical book into Japanese using French and Dutch dictionaries, and they wrote a book titled “Kaitai Shinsho (解体新書).” Following this translation, books on European history, economics, and politics were translated. These books inspired new ideas and influenced intellectual thought.

Schooling thrived in society. Each feudal domain operated its own schools for the sons of the daimyo’s retainers. Townspeople’s children attended schools called terakoya (寺子屋: unofficial neighborhood schools) to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Pressure from the Outside World

Although Japan was under the Sakoku policy (鎖国: national isolation policy), people were aware of events outside Japan. Since the early 17th century, Russian messengers had come to Japan to demand trade (in 1792 and 1804). In 1808, English ships arrived in Nagasaki. In 1825, the Tokugawa bakufu ordered the firing of guns on any ships that came close to Japan. In 1842, following England’s victory in the Opium War against the Qing dynasty, the Bakufu decided to supply foreign ships with food and fuel. They feared facing the same fate as the Qing. In 1846, the U.S. sent a fleet commander to Japan to establish diplomatic relations, but the Bakufu refused. The U.S. needed Japan to open its ports to get supplies of food, water, and fuel for its whaling ships in the Pacific Ocean.

In 1853, Fleet Commander Perry* arrived at Uraga (浦賀: a port in Japan) with four warships, demonstrating American military power to open the country. The Tokugawa bakufu had no clear policy for handling such a situation and recognized that it was difficult to maintain the isolation policy any longer.

In 1854, the “Japan-U.S. Treaty of Amity and Friendship” was signed. After that, Japan made treaties with England, Russia, France, and the Netherlands. This ended more than 200 years of Sakoku (the national isolation policy), and Japan opened several ports to foreign ships.

However, these treaties caused many problems. The treaties were unfair, leading to shortages of everyday necessities; as a result, prices rose. Also, a large amount of gold flowed out of Japan. This was due to differences in the gold-to-silver exchange rate between Japan and Europe. In Japan, the exchange rate was 1 gold coin to 5 silver coins, whereas in Europe it was 1 gold coin to 15 silver coins.

In addition to these issues, there were more problems: who should succeed the current shogun, Tokugawa Yesada (徳川家定), since he had no heir. During this chaotic period, many feudal domains opposed one another, seeking a shogun whose political ideas aligned with their own. Many conflicts had already led to major battles among the domains, and there were additional reasons for them to oppose the bakufu.

Now, the foundation of the Tokugawa Bakufu has begun to fall apart. The Choshu-han (Choshu domain) and the Satsuma-han (Satsuma domain) were the main forces opposing the Tokugawa bakufu. At first, they opposed each other. However, after several tense incidents, they decided to reconcile and work together against the Bakufu, realizing it was not the time to fight among themselves. England, recognizing that the Bakufu no longer held much power, began to align more closely with the emperor’s side, whereas France sided with the Tokugawa. England and France almost went to war over Japan.

In 1867, Tokugawa Yoshinobu issued the “Restoration of Imperial Rule (Taisei Hokan, 大政奉還).” In 1868, the Tokugawa clan vacated Edo Castle, and the Meiji Emperor moved in. This site is now Kokyo (皇居: Imperial Palace), where the current Emperor resides.

Many prominent political figures actively participated in the overthrow of the Tokugawa bakufu. Among them are Ito Hirobumi (伊藤博文), Okubo Toshimichi (大久保利通), Shimazu Nariakira (島津斉彬), and Hitotsubashi Yoshinobu (一橋慶喜). They established a new system of government, the Meiji Shin Seifu (明治新 ), with the emperor at its core.

Today, the original Edo-jo (Castle) was destroyed by a large fire. However, the original moat, the massive stone walls, and a beautiful bridge called Nijyu-bashi (二重 橋, below) still remain. Large garden areas are open to the public. This area is famous for its beautiful cherry blossoms. The Imperial Palace is located in front of and within walking distance of the Marunouchi side of Tokyo Station.

Today, Japanese people enjoy historical dramas set during the Meiji Ishin (Restoration), and we often see these on TV and in movies. These stories feature Saigo Takamori (西郷隆盛), Sakamoto Ryoma (坂本龍馬), and the Shinnsen-gumi (新撰組). Although fictional, the film The Last Samurai is set during this period, featuring Saigo Takamori.

Imperial Palace (From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository ).

*Perry

Commodore M.C. Perry visited Japan twice with four warships. In 1853, he carried a sovereign diplomatic letter from the President of the U.S. The following year, he returned to demand a response to the letter. After the expedition, Perry wrote a book about his journey, “Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, Under the Command of Commodore M.C. Perry, United States Navy by Order of the Government of the United States.” In this book, he describes Japan very favorably —its beautiful scenery, the ingenuity of its people, and the lively, active women — through his drawings.

Although it was a long, tough negotiation between the Edo Bakufu and Perry, there were several enjoyable moments. Perry gifted Japan a 1:4-scale model steam locomotive, a sewing machine, and more. The Japanese arranged a sumo match and offered gifts, such as silk, lacquerware, and other items. The Japanese prepared elaborate banquets for the American diplomats, and Perry invited Japanese officials to his feast. The highlight was when Perry served a dessert at the end of the dinner. Perry printed each guest’s family crest on a small flag and placed it on the dessert.

Before starting his expedition, he expected tough negotiations ahead. Therefore, he researched what the Japanese would enjoy and found that they enjoyed parties a lot. He brought skilled chefs and loaded the ship with livestock for future parties. He entertained Japanese officials with whiskey, wine, and beer. Initially, the U.S. wanted Japan to open five ports, while the Bakufu was willing to open only one. Ultimately, both sides agreed to open three ports.

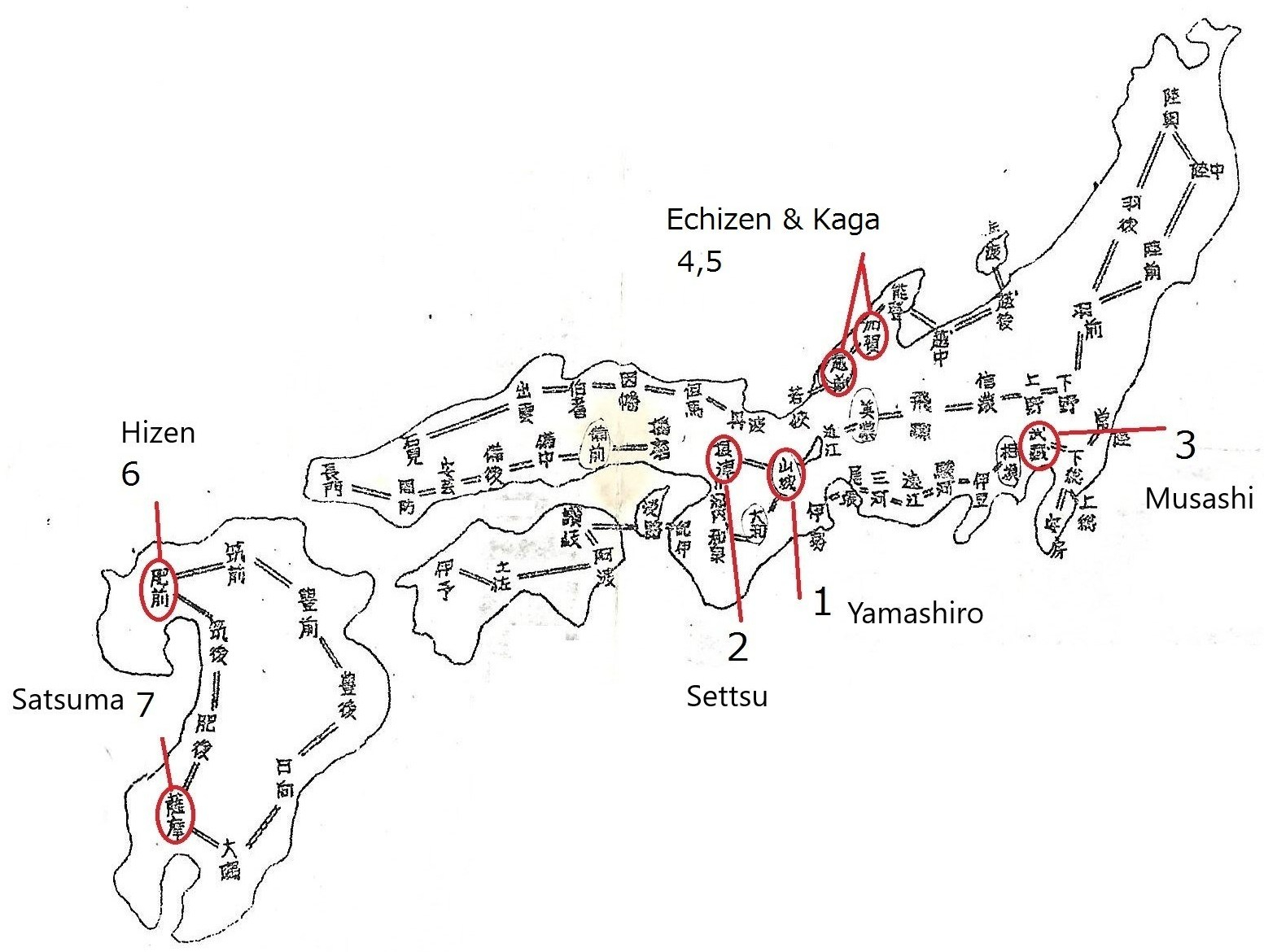

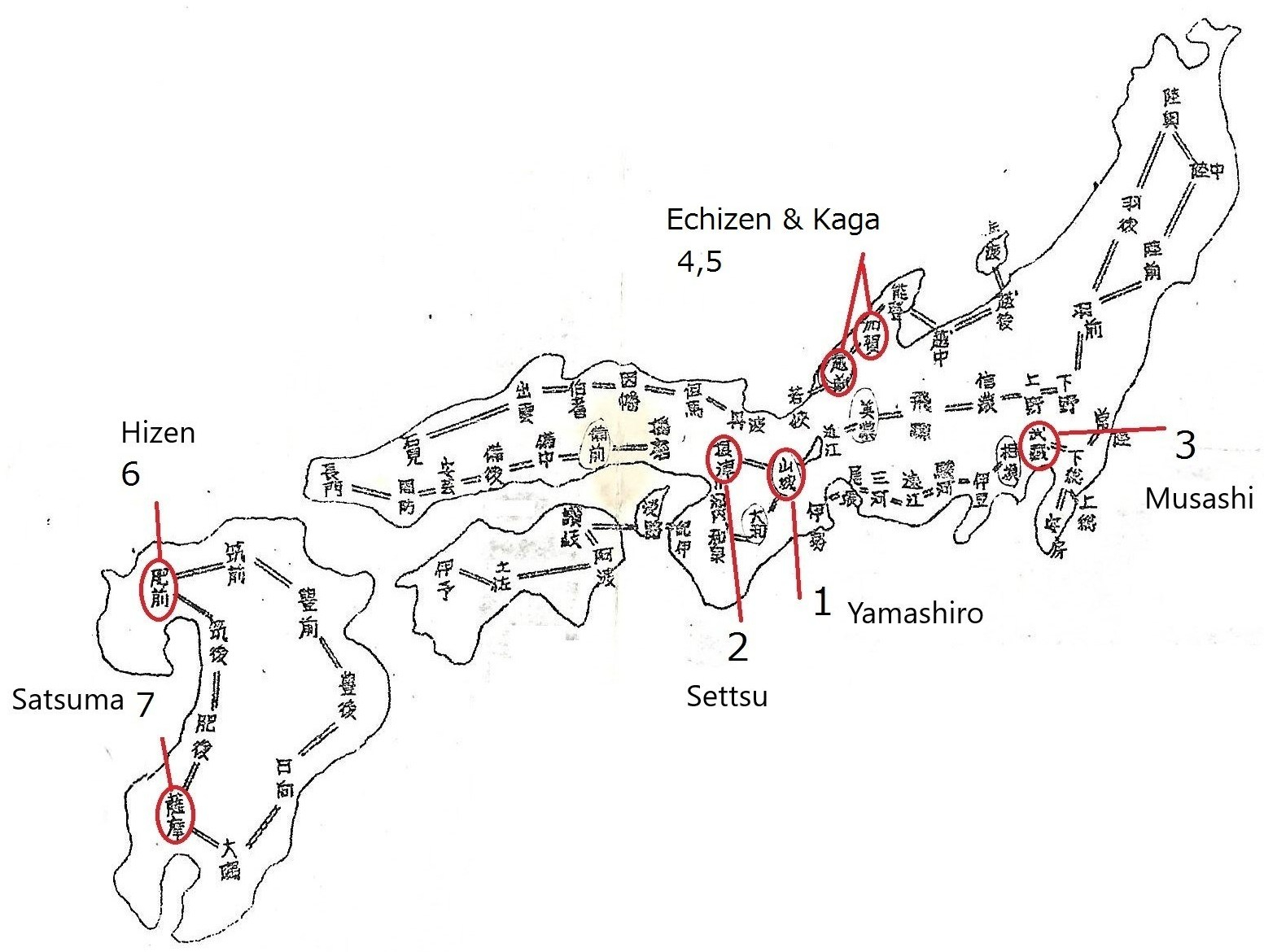

This chapter is a detailed part of Chapter 28, Shin-t Main 7 Regions (part B). Please read Chapter 28 before reading this chapter. Below are regions 3 and 7.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

3.Musashi (Edo)

We also find many famous swordsmiths in Edo. They were Yasutsugu (康継), Kotetsu (虎徹), Noda Hankei (野田繁慶), Hojoji Masahiro (法成寺正弘), and their followers.

Two photos below are swordsmiths from Musashi (武蔵: Tokyo).

Yasutsugu From the Sano Museum Catalogue. (Permission to use granted)

Yasutsugu From the Sano Museum Catalogue. (Permission to use granted)

Characteristics of Yasutusgu (康継) ——Shallow curvature; chu-gissaki (medium kissaki); a wide notare hamon, midare, or o-gunome (occasionally double gunome); traces of Soshu-den and Mino-den; a wood-grain pattern mixed with masame on the shinogi-ji.

Kotetsu (虎徹) from Sano Museum Catalogue, (permission to use granted)

Kotetsu (虎徹) from Sano Museum Catalogue, (permission to use granted)

Here is the famous Kotetsu. His formal name was Nagasone Okisato Nyudo Kotetsu (長曽祢興里入道虎徹). Kotetsu started making swords after turning 50. Before that, he was an armor maker.

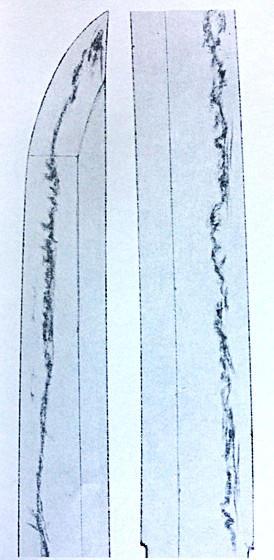

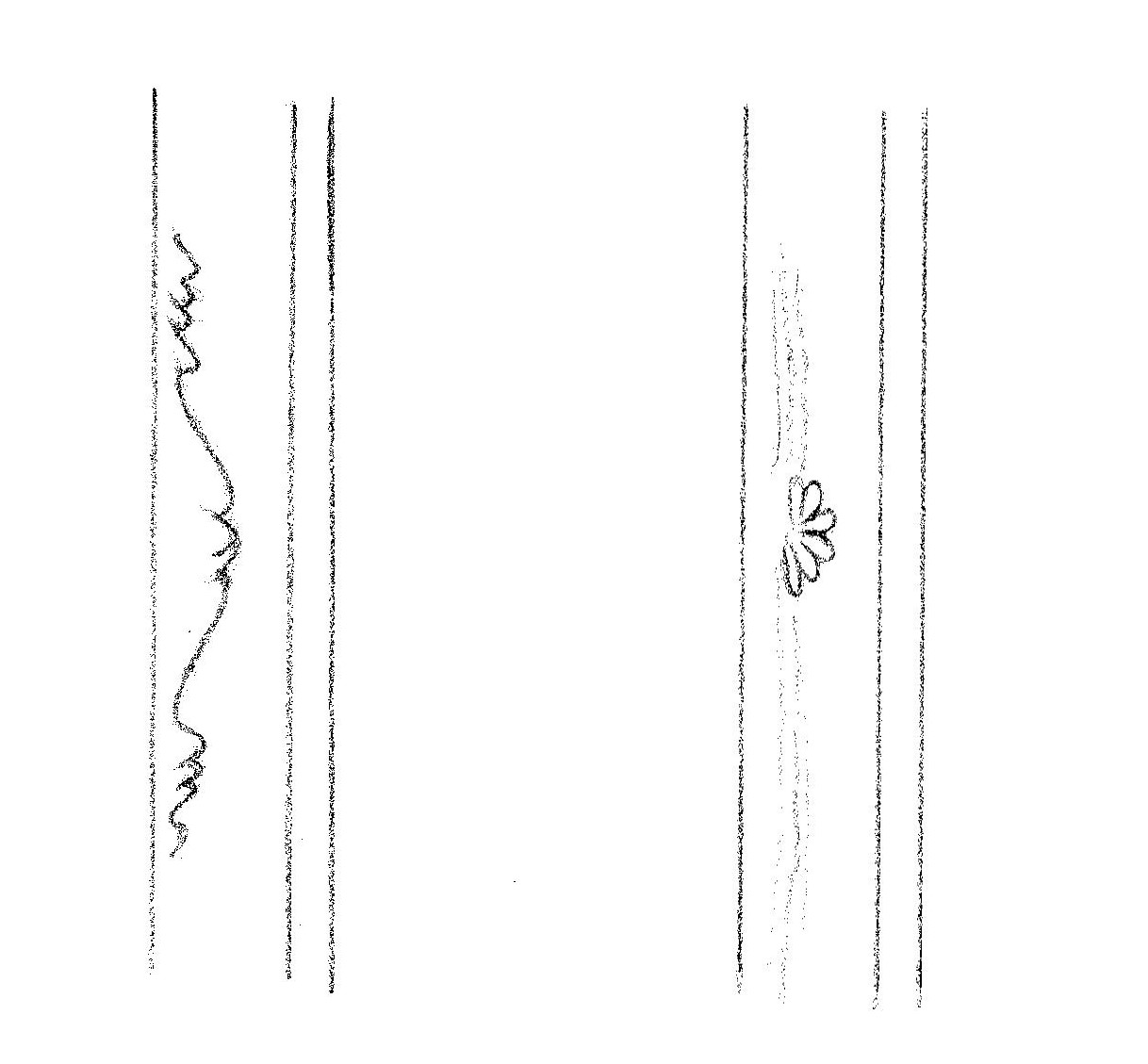

The characteristics of Kotetsu ———————— A shallow curvature and wide width, a wide tempered line with nie. A small irregular hamon surrounds the machi area, transitioning into a wide suguha-like notare in the upper area. Fine nie, komaru–boshi with a short turn back. The ji-hada is a fine-grained wood with burl. Occasionally, o-hada (black core iron shows through) appears in the lower part above the machi area. The illustration above shows a thick-tempered line with nie, a typical feature of Kotetsu. Once you see it, you will remember it. The next region is 7 (skip 4, 5, and 6)

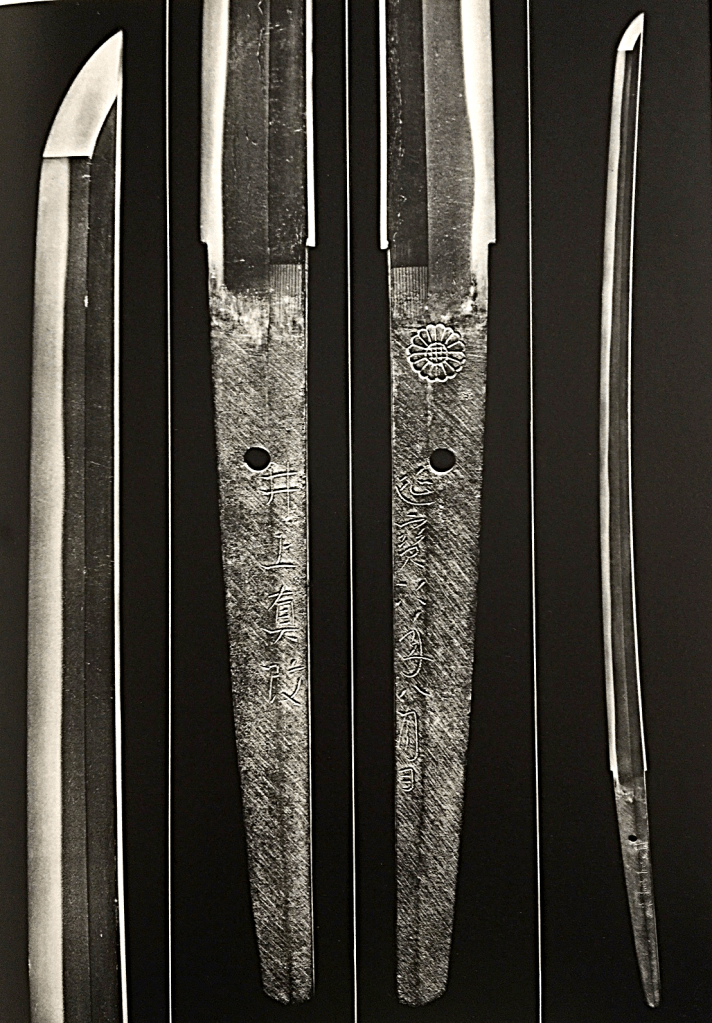

Miyahara Mondonosho Masakiyo (宮原主水正正清) from Sano Museum Catalogue (permission to use granted).

Miyahara Mondonosho Masakiyo (宮原主水正正清) from Sano Museum Catalogue (permission to use granted).

Miyahara Mondonosho Masakiyo was highly respected by the Shimazu family of Satsuma- han (the Satsuma domain in Kyushu). Later, he was chosen to travel to Edo to forge swords for Shogun Yoshimune.

Mondonosho Masakiyo’s characteristics————- Well-balanced sword shape, shallow curvature, and wide and narrow hamon mixed with squarish hamon and pointed hamon as shown in the photo above. He engraved the Tokugawa family’s Aoi crest (the hollyhock crest) on the nakago.

Chapter 61 is a detailed part of Chapter 27, Shinto Main 7 Regions (part A). Please read Chapter 27 before reading this section.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

Chapter 27, Shin-to Main 7 Regions (Part A), and Chapter 28, Shin-to Main 7 Regions (Part B), describe an overview of the seven main regions. This chapter and the next chapter show photos of representative swords from these regions. They are Yamashiro (山城, in Kyoto), Settsu (摂津, today’s Osaka), Musashi (武蔵, Edo), and Satsuma (薩摩, Kyushu). However, Echizen (越前), Kaga (加賀), and Hizen (肥前) are omitted.

With ko-to swords, features such as the condition of the hamon, kissaki size, length, and shape of the nakago, etc., indicate when the sword was made. During the ko-to period, Bizen swordsmiths produced Bizen-den swords, Yamashiro swordsmiths made Yamashiro-den swords, and Mino swordsmiths made Mino-den swords. However, during the shin-to period, that is not the case. The den and the swordsmith’s location often do not match. For shin-to swords, we study the swordsmiths and swords from the seven main regions along with their characteristics.

Regarding swords made during the ko-to period, if a sword has a wide hamon line with nie, usually, its ji-hada shows a large wood grain or a large burl grain. Also, when you see a narrow hamon line, it typically features a fine ji-hada.

However, with shin-to swords, if a sword shows a wide hamon with nie, it often has a small wood grain or small burl grain pattern on ji-hada. If it has a narrow hamon line, it may have a large wood grain pattern on the ji-hada. This is a shin-to characteristic.

Here is an exception: some early Soshu-den swords from the late Kamakura period may show a wide hamon with nie, which has small burls on the ji-hada. Because of that, whether it is ko-to or shin-to can be confusing. Even so, other features such as ji-hada or other parts should indicate whether it is shin-to or ko-to.

Yamashiro (山城: Kyoto)

Horikawa Kunihiro (堀川国広) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Horikawa Kunihiro (堀川国広) From Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Horikawa Kunihiro (堀川国広)

Horikawa Kunihiro was regarded as a master swordsmith among shin-to swordsmiths. He forged swords in many styles with various characteristics. The hamon types are o-notare, o-gunome, togari-ba (pointed hamon), chu-suguha with hotsure (frayed look), hiro-suguha with a sunagashi effect, inazuma, and kinsuji. Kunihiro preferred to shape his swords to resemble an o-suriage (shortened Nanboku-cho style long sword). Kunihiro‘s blades give a powerful impression. Kunihiro‘s swords often feature beautiful carvings; designs include dragons, Sanskrit letters, and more. Because he created swords in many different styles, there is no general characteristic that defines his work other than the hamon mainly being nie. His ji-hada is finely forged.

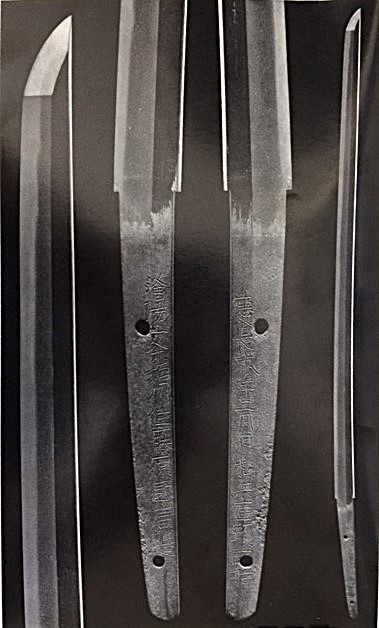

Iga-no-Kami Kinnmichi (伊賀守金道) Dewa Daijyo Kunimichi (出羽大掾国路) Both Juyo Token (重要刀剣), once my family owned, photos were taken by my father.

Iga-no-Kami Kinnmichi (伊賀守金道) Dewa Daijyo Kunimichi (出羽大掾国路) Both Juyo Token (重要刀剣), once my family owned, photos were taken by my father.

Iga-no-Kami Kinmichi ( 伊賀守金道)

The Kinmichi family is called the Mishina group. Refer to 27 Shinto Main 7 Regions Part A. Iga-no-Kami Kinmichi was awarded the Japanese Imperial chrysanthemum crest.

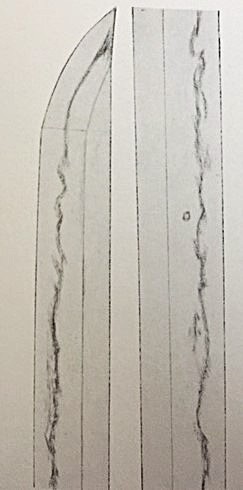

The characteristics of Kinmichi ——– Wide sword, shallow curvature, an extended kissaki, sakizori (curvature at 1/3 top), a wide tempered line, kyo-yakidashi (see 27 Shinto Main 7 Regions A ), hiro-suguha (wide straight hamon), o-notare (large wavy), yahazu-midare, hako-midare (refer to 24 Sengoku Period Tanto). Mishina-boshi, refer to 27 Shin-to Main 7 Regions A. Fine wood burl, masame appear in the shinogi-ji area.

Dewa Daijo Kunimichi (出羽大掾国路)

Dewa Daijo Kunimichi was the top student of Horikawa Kunihiro. The right photo above. Like Kunihiro, the sword resembles a shortened Nanboku-cho sword. Shallow curvature, a wide body, a somewhat elongated kissaki, and fukura-kareru (less arch in fukura). Wide tempered lines, large gunome, nie with sunagashi, or inazuma shows. Double gunome (two gunome side by side) appears. Fine ji-hada.

Settu (Osaka) is home to many famous swordsmiths. They are Kawachi-no-Kami Kunisuke (河内守国助), Tsuda Echizen-no-Kami Sukehiro (津田越前守助広), Inoue Shinkai (井上真改), and Ikkanshi Tadatsuna (一竿子忠綱), among others. The main characteristic of the Settsu (Osaka) sword ——– The surface is beautiful and fine, almost like a solid surface with no pattern or design. The two photos below are of the Settsu sword.

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna from the Sano Museum Catalogue. Permission granted to use.

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna from the Sano Museum Catalogue. Permission granted to use.

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna (一竿子忠綱)

Ikkanshi Tadatsuna was famous for his carvings. His father was also a well-known swordsmith, Omi-no-Kami Tadatsuna (近江守忠綱). Consequently, he was known as Awataguchi Omi-no-Kami Fujiwara Tadatsuna (粟田口近江守藤原忠綱), as shown in the nakago photo above.

The characteristics of Ikkanshi Tadatsuna ——-A longer kissaki and a wide-tempered line with nie. The Osaka yakidashi (transition between the suguha above machi and midare is smooth. Refer to 27 Shin-to Sword – Main 7 Regions (Part A) for details on Osaka yakidashi. O-notare with gunome, komaru-boshi with a turn back, and very fine ji-hada with almost no pattern on the surface.

Inoue Shinkai (井上真改) from “Nippon-to Art Swords of Japan” The Walter A. Compton Collection

Inoue Shinkai (井上真改) from “Nippon-to Art Swords of Japan” The Walter A. Compton Collection

Inoue Shinkai (井上真改)

Inoue Shinkai was the second generation of Izumi-no-Kami Kunisada (和泉守国貞), who was a student of Kunihiro. The characteristic of Inoue Shinkai’s swords —————- Osaka yakidashi, the tempered line gradually widens toward the top. O-notare and deep nie. Very fine ji-hada with almost no surface design.

Chapter 60 is a detailed part of Chapter 26, Overview of Shinto (新刀概要). Please read Chapter 26 before reading this section.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The difficulty of Shin-to Kantei

Regarding swords from the ko-to period, you can estimate when they were made by analyzing their style and shape. Several factors indicate which period and which Gokaden (五ヶ伝) created the sword by examining several points, such as the appearance of the hamon or the appearance of the ji-gane. However, swords from the shin-to period do not follow this method.

Although there are differences among shin-to swords made during the early Edo period, around the Keicho (慶長: 1596 ~) era, the middle Edo period, that is around the Kanbun (寛文: 1661 ~) era, and the late Edo period, that is the Genroku era (元禄: 1688 ~), these differences are not much.

The same applies to the Gokaden (五ヶ伝) during the shin-to period. In the ko-to time, Bizen swordsmiths forged swords with Bizen characteristics. Swords made by Yamato swordsmiths usually showed the Yamato-den features. However, during the shin-to period, a swordsmith from one specific den sometimes forged blades in the style of another den’s features. As a result, it is difficult to determine the maker of a particular sword.

For shin-to, we will study the characteristics of the seven main locations, which will be discussed in the following chapters.

Picturesque Hamon

During and after the Genroku era (元禄1688 – 1704), some picturesque hamon style became trendy. Several swordsmiths created picturesque hamon on wakizashi and short swords. As it gained popularity, especially among foreigners, most of these swords were exported from Japan during the Meiji Restoration. Today, very few remain in Japan.

The swordsmiths who made picturesque Hamon

Yamashiro (山城) area ———————————-Iga-no-kami Kinmichi (伊賀守金道), Omi-no-kami Hisamichi (近江守久道)

Settsu (摂津) area ———————————Tanba-no-Kami Yoshimichi (丹波守吉道) Yamato-no-Kami Yoshimichi (大和守吉道)

Below are examples. Fuji is the Mount Fuji design. Kikusui is a chrysanthemum in the water.

Chapter 59 is a detailed section of Chapter 25 Edo Period History (江戸時代歴史). Please read Chapter 25 before reading this part.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

Battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原合戦)

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉), the most powerful figure during the Sengoku and Momoyama periods, died in 1598. His heir, Hideyori (秀頼), was only five years old. Before his death, Hideyoshi established a council system composed of the top five daimyo to oversee Hideyori’s affairs as regents until he reached adulthood.

At Hideyoshi’s deathbed, all five Daimyo agreed to serve as guardians of Hideyori. However, over time, Ishida Mitsunari (石田三成) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康) began to disagree. In 1600, finally, the two main Daimyo clashed, leading to the Battle of Sekigahara. One side is called Seigun (the Western army), led by Ishida Mitsunari and the other is Togun (the Eastern army), led by Tokugawa Ieyasu. All the daimyo across the country sided either with Tokugawa or with Ishida Mitsunari. It is said that Mitsunari’s forces had 100,000 men, while Tokugawa’s forces had 70,000. Ieyasu had fewer soldiers, but he ultimately won. Ieyasu became the chief retainer of the Toyotomi clan, meaning he was virtually the top figure since Hideyori was still a child.

In 1603, Ieyasu became a Shogun. Now, Ieyasu took control of Japan, establishing the Tokugawa Bakufu (government) in Edo and eliminating the council system.

Toyotomi Hideyori lived with his mother, Yodo-gimi (or Yodo-dono), at Osaka Castle, which Hideyoshi had built before his death. Over time, tensions arose between Hideyori and Yodo-gimi in Osaka and Ieyasu in Edo. Yodo-gimi was a proud and headstrong person, and she had good reasons for it. She was the niece of Oda Nobunaga, the wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and the mother of Hideyori, the head of the Toyotomi clan. Later, her pride led her into trouble and contributed to the Toyotomi clan’s downfall.

Siege of Osaka: Winter (1614) and Summer ( 1615) Campaigns

During the 15 years between the Battle of Sekigahara and the Siege of Osaka Castle, tensions between the Tokugawa Shogunate and the Toyotomi clan steadily increased. Before the Battle of Sekigahara, the Toyotomi clan ruled Japan. After Sekigahara, the Tokugawa bakufu took control of Japan. The Toyotomi clan lost many key advisors and vassals in the battle. As a result, Toyotomi’s power remained centered on Yodo-gimi. By the time of the siege, Hideyori had grown into a fine young man, but Yodo-gimi had overly protected and controlled her son. She wouldn’t even let Hideyori practice kendo (the traditional Japanese swordsmanship), claiming it was too dangerous.

She persistently acted as if the Toyotomi clan still held the highest power. Tokugawa Ieyasu tried to ease tensions by arranging for his granddaughter, Sen-hime, to marry Hideyori. A few advisors suggested that Yodo-gimi should yield to Tokugawa, but she insisted that Tokugawa must subordinate himself to Toyotomi. Rumors began circulating that the Toyotomi side was recruiting and gathering many ronin (unemployed samurai) within Osaka Castle. Several key figures tried to mediate between the Toyotomi and Tokugawa clans but were unsuccessful.

Finally, Ieyasu led his army to Osaka, and in November 1614, he launched a campaign to siege Osaka Castle (the Winter Campaign). It is said that the Toyotomi side had 100,000 soldiers, though some were merely mercenaries. However, Osaka Castle was built almost like a fortress, making it very difficult to attack. The Tokugawa army attacked fiercely and fired cannons daily, but they realized the castle was so well built that it was a waste of time to keep trying.

Eventually, both sides entered peace negotiations. They agreed on several items in the treaty. One of them was to fill the outer moat of Osaka Castle. However, the Tokugawa side filled both the outer and inner moats. That angered the Toyotomi side, and they became suspicious that the Tokugawa might not keep the agreement.

Another agreement was the disarmament of the Toyotomi clan. However, the Toyotomi side kept their soldiers inside the castle. Tokugawa issued a final ultimatum to the Toyotomi side: remove all soldiers from the castle or vacate it. Yodo-gimi refused both demands.

After that, another siege started in the summer of 1615 (the Summer Campaign). It is said that the Toyotomi had 70,000 men, whereas the Tokugawa had 150,000. Both sides fought in several battles here and there, but the early battles did not go well for either side due to thick fog, delayed troop arrivals, and miscommunication. The final battle took place at Osaka Castle. The Toyotomi decided to stay inside the castle, but soon, a fire broke out from within and burned the castle down. Yodo-gimi and Hideyori hid inside a storage building, waiting for Ieyasu’s response to their pleas for mercy. They hoped their daughter-in-law could negotiate the terms of the deal. However, it was not accepted, and both died inside the storage building.

Nene and Yodo-gimi

Nene was the lawful wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. She was a bright and wise person, despite not being of noble birth. Everyone respected her, including Tokugawa Ieyasu. Even Hideyoshi often valued her opinions on political matters. She helped Hideyoshi rise through the ranks. However, Nene was unable to have children. Toyotomi Hideyoshi sought out other women everywhere, hoping to produce an heir, but none could have his child except Yodo-gimi. Naturally, rumors circulated about who the real biological father was. Speculation pointed to several men, one of whom was Ishida Mitsunari.

伝 淀殿画像(possibly of Yodo-dono, but not confirmed)Owned by the Nara Museum of Art, Public Domain: Yodo-dono cropped.jpg from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.

Here are several pictures of 2019 San Francisco Sword Show that I attended last weekend. It was a such a pleasure meeting several of you guys. Mr. Yoshihara brought his grandson to this meeting as debut as a new sword maker. It is nice to see a next generation of sword maker.

Chapter 58 is a detailed section of Chapter 24, Sengoku Period Tanto. Please read Chapter 24, Sengoku Period Tanto, before reading this part.

The red circle above indicates the time we discuss in this section

Muramasa (村正)

This chapter discusses the famous Muramasa (村正). Usually, many well-known swordsmiths come from one of the Goka-den (五家伝: the five main schools: Yamashiro-den, Bizen-den, Soshu-den, Yamato-den, and Mino-den). However, Muramasa was not from Goka-den but from Ise Province. The first-generation Muramasa was known as a student of He’ian-jo Nagayoshi (平安城長吉) of Yamashiro-den. The Muramasa family existed through the mid-Muromachi period. They spanned three generations from the mid-Muromachi to the Sengoku period.

Below is one of Muramasa’s tantos, made during the Sengoku period. Since it was made during the Sengoku era, the blade shows the style of Sengoku-period swords. It reflects Mino-den characteristics, combined with Soshu-den traits.

Muramasa (村正) from Sano Museum Catalogue (permission granted)

Characteristics on this Tanto

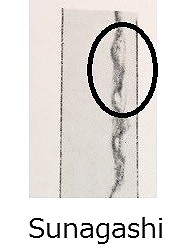

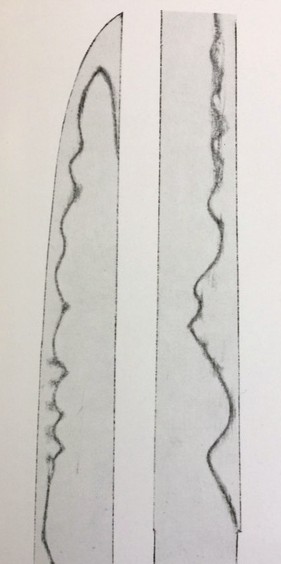

Muramasa’s tantos are typically about ten inches ± half an inch or so. Hirazukuri (平作り). Thin blades with a sharp look. The nioi base with small nie and sunagashi patterns (brushed sand-like patterns, as shown in the illustration below) appears. The boshi (the top part of the hamon) is jizo (a side view of a human head). The tempered line varies with both wide and narrow areas. Some areas are so narrow, almost close to the edge of the blade, while others are broader. Hako midare (box-like shape) and gunome (lined-up bead pattern) appear. O-notare (large, gentle waviness) is a signature characteristic of Muramasa. The pointed-tempered line is a typical characteristic of Mino-den (Sanbon-sugi). Refer to Chapter 23, Sengoku Period Sword, and Chapter 24, Sengoku Period Tanto.